Summary: Researchers uncovered that the vestibulo-ocular reflex, a vital brain circuit stabilizing gaze during body tilts, matures independently of sensory input in newborns. This reflex, essential for perceiving a stable environment, enables the eyes to counter-rotate with body movements.

Experiments with zebrafish revealed that neuromuscular junctions, rather than brain regions, dictate the reflex’s maturation pace. These findings challenge assumptions about sensory feedback in early development and could inform treatments for balance and eye movement disorders, such as strabismus.

Key Facts:

- Independent Maturation: The vestibulo-ocular reflex matures without sensory input from vision or balance organs in newborns.

- Neuromuscular Junction Role: The slowest-maturing part of the reflex circuit is at the neuromuscular junction, not in the brain.

- Clinical Potential: Insights may lead to therapies for eye movement disorders and childhood balance problems.

Source: NYU Langone

An ancient brain circuit, which enables the eyes to reflexively rotate up as the body tilts down, tunes itself early in life as an animal develops, a new study finds.

Led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the study revolves around how vertebrates, which includes humans and animals spanning evolution from primitive fish to mammals, stabilize their gaze as they move.

To do so they use a brain circuit that turns any shifts in orientation sensed by the balance (vestibular) system in their ears into an instant counter-movement by their eyes.

Called the vestibulo-ocular reflex, the circuit enables the stable perception of surroundings. When it is broken — by trauma, stroke, or a genetic condition — a person may feel like the world bounces around every time their head or body moves.

In adult vertebrates, it and other brain circuits are tuned by feedback from the senses (vision and balance organs).

The current study authors were surprised to find that, in contrast, sensory input was not necessary for maturation of the reflex circuit in newborns.

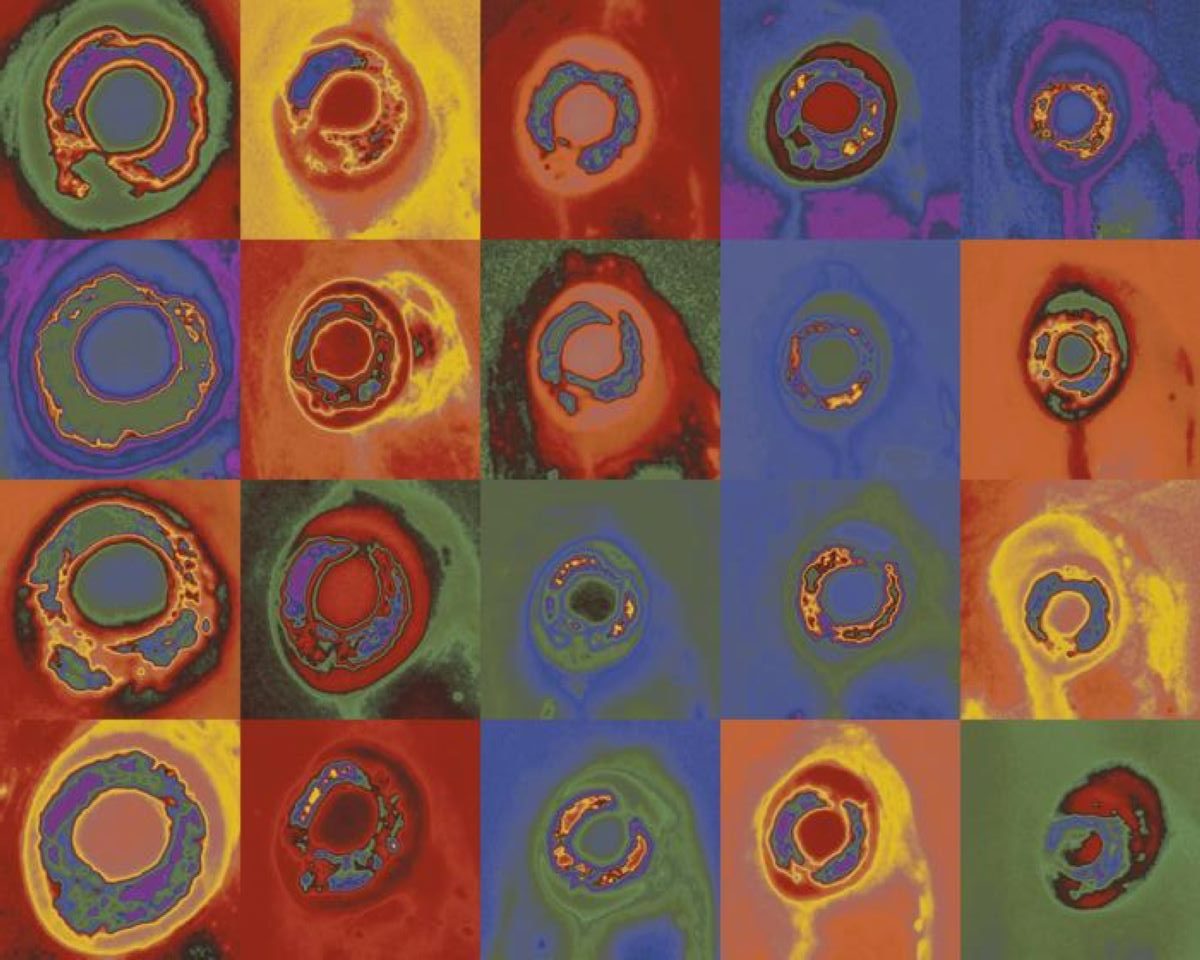

Published online January 2 in the journal Science, the study featured experiments done in zebrafish larvae, which have a similar gaze stabilizing reflex to the one in humans.

Further, zebrafish are transparent, so researchers litterally watched brain cells called neurons mature to understand the changes that let a newborn fish rotate its eyes up appropriately as its body tilts down (or its eyes down as its body tilts up).

“Discovering how vestibular reflexes come to be may help us find new ways to counter pathologies that affect balance or eye movements,” says study senior author David Schoppik, PhD, associate professor in the Departments of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, Neuroscience & Physiology, and the Neuroscience Institute, at NYU Langone Health.

Split-Second Tilts

To test the long-held assumption that the reflex is tuned by visual feedback, the research team invented an apparatus to elicit the reflex by tilting and monitoring the eyes of zebrafish that were blind since birth. The team observed that the ability of the fish to counterrotate their eyes after tilt was comparable to larvae that could see.

Although past studies established that sensory input helps animals learn to move properly in their environment, the new work suggests that such tuning of the vestibulo-ocular reflex comes into play only after the reflex has fully matured.

Remarkably, another set of experiments showed that the reflex circuit also reaches maturity during development without input from a gravity-sensing vestibular organ called the utricle.

Because the vestibulo-ocular reflex could mature without sensory feedback, the researchers theorized that the slowest-maturing part of the brain circuit must set the pace for the development of the reflex.

To find the rate-limiting part, the research team measured the response of neurons throughout development as they gave zebrafish split-second body tilts.

The researchers found that central and motor neurons in the circuit showed mature responses before the reflex had finished developing.

Consequently, the slowest part of the circuit to mature could not be in the brain as long assumed, but was found instead to be at the neuromuscular junction — the signaling space between motor neurons and the muscle cells that move the eye.

A series of experiments revealed that only the pace of maturation of the junction matched the rate at which fish improved their ability to counter-rotate their eyes.

Moving forward, Dr. Schoppik’s team is funded to study their newly detailed circuit in the context of human disorders. Ongoing work explores how failures of motor neuron and neuromuscular junction development lead to disorders of the ocular motor system, including a common misalignment of the eyes called strabismus (a.k.a., lazy eye, crossed eyes).

Just upstream of motor neurons in the vestibulo-ocular circuit are interneurons that sculpt incoming sensory information and integrate what the eyes see with balance organs.

Another of Dr. Schoppik’s grants seeks to better understand how the function of such cells is disrupted as balance circuits develop, with the goal of helping the five percent of children in the U.S. wrestling with some form of balance problem.

“Understanding the basic principles of how vestibular circuits emerge is a prerequisite to solving not only balance problems, but also brain disorders of development,” says first study author Paige Leary, PhD. She was a graduate student in Dr. Schoppik’s lab who led the study but has since left the institution.

Along with Drs. Schoppik and Leary, study authors from the departments of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, Neuroscience & Physiology, and the Neuroscience Institute, at NYU Langone Health included Celine Bellegarda, Cheryl Quainoo, Dena Goldblatt, and Basak Rosti.

Funding: The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders grants R01DC017489 and F31DC020910, and by National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant F99NS129179. The National Science Foundation also supported the study through graduate research fellowship DGE2041775.

About this visual development and neuroscience research news

Author: Gregory Williams

Source: NYU Langone

Contact: Gregory Williams – NYU Langone

Image: The image is credited to NYU Grossman School of Medicine

Original Research: Closed access.

“Sensation is Dispensable for the Maturation of the Vestibulo-ocular Reflex” by David Schoppik et al. Science

Abstract

Sensation is Dispensable for the Maturation of the Vestibulo-ocular Reflex

Vertebrates stabilize gaze using a neural circuit that transforms sensed instability into compensatory counterrotation of the eyes.

Sensory feedback tunes this vestibulo-ocular reflex throughout life.

We studied the functional development of vestibulo-ocular reflex circuit components in the larval zebrafish, with and without sensation.

Blind fish stabilize gaze normally, and neural responses to body tilts mature before behavior.

In contrast, synapses between motor neurons and the eye muscles mature with a time course similar to behavioral maturation.

Larvae without vestibular sensory experience, but with mature neuromuscular junctions, had a strong vestibulo-ocular reflex.

Development of the neuromuscular junction, and not sensory experience, therefore determines the rate of maturation of an ancient behavior.