Summary: Exposure to alcohol in early fetal development hinders the development of brain areas associated with motor control, and the deficits can be detected in-utero via MRI neuroimaging.

Source: Oregon Health and Sciences University

New images reveal the earliest impairments to nonhuman primate fetal brain development due to alcohol ingested by the mother, in a study led by scientists at Oregon Health & Science University involving rhesus macaques.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed impairments to brain growth during the third trimester of pregnancy, even though the fetus was exposed to alcohol only during the first trimester.

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, highlights the danger of binge drinking early in a pregnancy, even before a woman realizes she’s pregnant. It also suggests the potential benefit of using in-utero imaging to detect signs of fetal-alcohol syndrome before birth.

“The earlier the detection, the better,” said senior author Chris Kroenke, Ph.D., associate professor in the Division of Neuroscience at the Oregon National Primate Research Center at OHSU. “Predicting risks for specific impairments means that therapy can start soon after the baby is born, when the brain has the greatest plasticity.”

The study builds upon recent advancements in the quality and resolution of magnetic resonance imaging methods used to examine the fetal brain in utero.

“The goal of this study was to assess the sensitivity of this common clinical diagnostic to detect the impact of drinking binge level intakes of alcohol [4-6 drinks] early in pregnancy to model patterns of drinking in women before they know they are pregnant,” said co-author Kathleen Grant, Ph.D., professor and chief of the Division of Neuroscience at the primate center.

Researchers at the primate center monitored a total of 28 pregnant macaques, measuring brain development through MRIs at three stages of pregnancy. In an experiment that would not be possible to conduct in people, half of the macaques consumed the daily human equivalent of six alcoholic drinks per day while the rest consumed no alcohol.

Imaging during the course of the pregnancy revealed a difference in fetal brain development by the 135th day of a 168-day gestational term, at the beginning of the third trimester. Imaging revealed no difference with the control group measured during the second trimester.

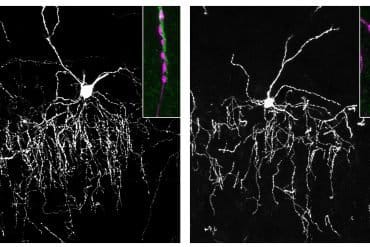

Electrophysiological recordings of the brains following MRI suggested the differences are functionally significant. Aside from validating the potential usefulness as an early diagnostic tool for fetal alcohol syndrome, researchers say the images generated during the study were of high enough quality that they expect it to be useful as a point of comparison for other scientists working in the field.

“The brain atlases described in our paper have been uploaded to a website where other researchers can access it,” Kroenke said.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grants R01AA021981, P51OD011092, R011NS055064, and R01AA024757. The work was reviewed and approved by the OHSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

About this neuroscience research article

Source:

Oregon Health and Sciences University

Media Contacts:

Erik Robinson – Oregon Health and Sciences University

Image Source:

The image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Closed access

“In utero MRI identifies consequences of early-gestation alcohol drinking on fetal brain development in rhesus macaques”. by Chris Kroenke et al.

PNAS doi:10.1073/pnas.1919048117

Abstract

In utero MRI identifies consequences of early-gestation alcohol drinking on fetal brain development in rhesus macaques

One factor that contributes to the high prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) is binge-like consumption of alcohol before pregnancy awareness. It is known that treatments are more effective with early recognition of FASD. Recent advances in retrospective motion correction for the reconstruction of three-dimensional (3D) fetal brain MRI have led to significant improvements in the quality and resolution of anatomical and diffusion MRI of the fetal brain. Here, a rhesus macaque model of FASD, involving oral self-administration of 1.5 g/kg ethanol per day beginning prior to pregnancy and extending through the first 60 d of a 168-d gestational term, was utilized to determine whether fetal MRI could detect alcohol-induced abnormalities in brain development. This approach revealed differences between ethanol-exposed and control fetuses at gestation day 135 (G135), but not G110 or G85. At G135, ethanol-exposed fetuses had reduced brainstem and cerebellum volume and water diffusion anisotropy in several white matter tracts, compared to controls. Ex vivo electrophysiological recordings performed on fetal brain tissue obtained immediately following MRI demonstrated that the structural abnormalities observed at G135 are of functional significance. Specifically, spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current amplitudes measured from individual neurons in the primary somatosensory cortex and putamen strongly correlated with diffusion anisotropy in the white matter tracts that connect these structures. These findings demonstrate that exposure to ethanol early in gestation perturbs development of brain regions associated with motor control in a manner that is detectable with fetal MRI.

Feel Free To Share This Neuroscience News.