Summary: Neuroimaging reveals people experience a diminished neural response in the anterior cingulate cortex when shown images of others with facial disfigurements. A similar response is also seen when people view other stigmatized people, such as those who are homeless. The diminished activity may explain why people are less empathetic toward those who have facial disfigurements and may help explain the underlying neural mechanism for dehumanization.

Source: University of Pennsylvania

People with attractive faces are often seen as more trustworthy, socially competent, better adjusted, and more capable in school and work. The correlation of attractiveness and positive character traits leads to a “beautiful is good” stereotype. However, little has been understood about the behavioral and neural responses to those with facial abnormalities, such as scars, skin cancers, birthmarks, and other disfigurements. A new study led by Penn Medicine researchers, which published today in Scientific Reports, uncovered an automatic “disfigured is bad” bias that also exists in contrast to “beautiful is good.”

“Judgements on attractiveness and trustworthiness are consistent across cultures, and these assumptions based on facial beauty are made extremely quickly. On the other hand, people with facial disfigurement are often targets of discrimination, which seems to extend beyond the specific effects of lower overall attractiveness and may tie in more with the pattern of results with stigmatized groups,” said the study’s lead author Anjan Chatterjee, MD, a professor of Neurology, and director of the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics. “In order to right any discrimination, the first step is to understand how and why such biases exist, which is why we set out to uncover the neural responses to disfigured faces.”

Neuroimaging studies show that seeing attractive faces evokes brain responses in reward, emotion, and visual areas compared to seeing faces of average attractiveness. Specifically, attractive faces evoke greater neural responses as compared to faces of average attractiveness in ventral occipito-temporal cortical areas, which process faces and other objects. Additionally, attractiveness correlates with increased activations in the anterior cingulate cortex and medial-prefrontal cortex–areas which are associated with rewards, empathy, and social cognition.

The researchers set out to evaluate the behavioral and brain reactions to disfigured faces and investigate whether surgical treatment mitigates these responses. In two experiments, the researchers used a set of photographs of patients with different types of facial anomalies, before and after surgical treatment, to test whether people harbor a “disfigured is bad” bias and to measure neural responses.

In the first experiment, a behavioral study with 79 participants, the researchers tested if people harbor implicit biases against disfigured faces and if such implicit biases were different from consciously aware, self-reported explicit biases. The behavioral experiment consisted of an implicit association test (IAT) and an explicit bias questionnaire (EBQ) to identify whether people have a negative bias for disfigured faces. For the IAT, the researchers used the set of before and after photographs as a stimulus. The EBQ consisted of 11 questions which query conscious biases against people with facial disfigurements. While the team found no indication of an explicit bias, they found that non-disfigured faces were preferred in the IAT. This bias was particularly robust for men.

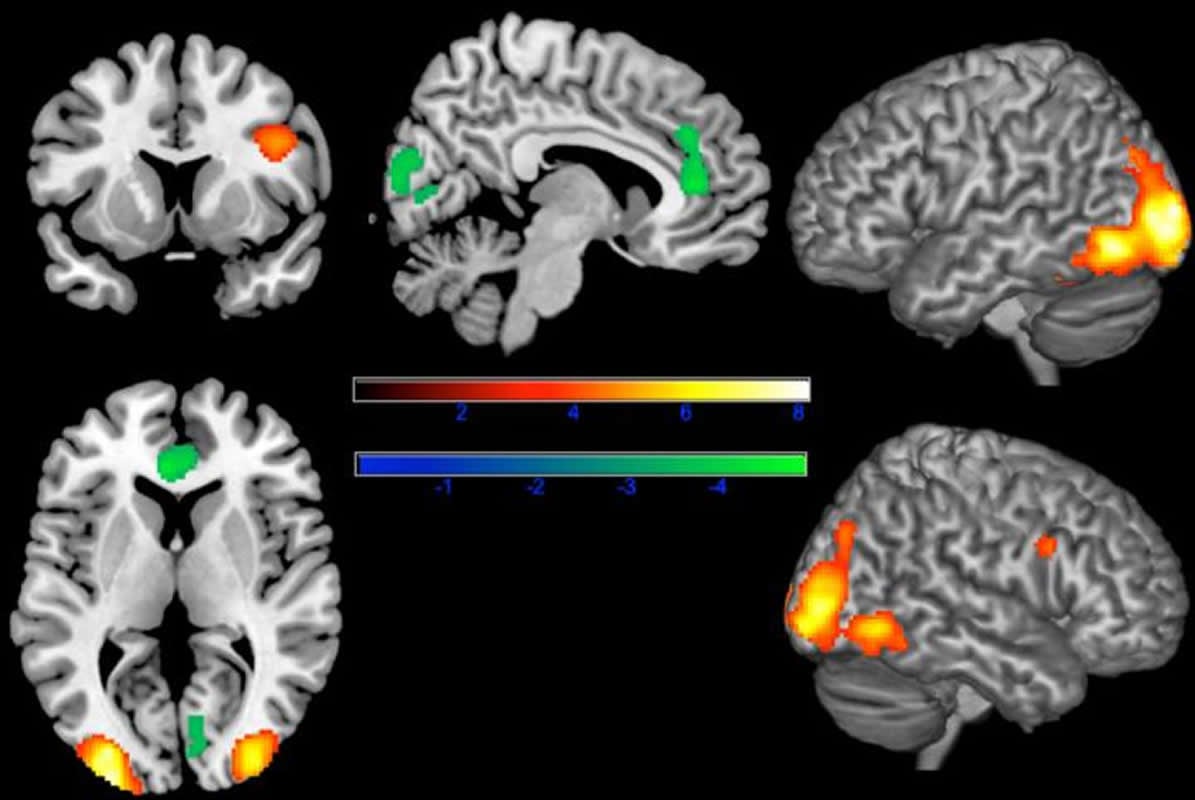

In a follow up functional MRI (fMRI) study with 31 participants, researchers tested brain responses to the same picture pairs. Participants judged the gender of each photograph they viewed. The researchers found increased neural responses in visual regions of the brain (the ventral occipito-temporal cortical areas) and decreases in regions associated with empathy (the anterior cingulate and medio-prefrontal cortex).

In sum, the authors found that people have implicit negative biases against people with disfigured faces, without knowingly harboring such biases. The diminished neural responses in the anterior cingulate cortex suggests that people are less empathetic when looking at individuals with disfigurement–this is also a potential neural marker of dehumanization, as diminished neural responses in the anterior cingulate cortex is also observed in response to other stigmatized people, such as the homeless and drug addicts.

“The emphasis of attractiveness and its association with positive attributes highlights the pervasive effect of appearance in social interaction. Chatterjee said. “While we found that corrective surgery mitigates negative social and psychological responses to people with facial anomalies, we are also exploring alternative strategies to minimize bias towards people with facial conditions.”

Funding: This work was supported by the Penn Center for Human Appearance and the Global Wellness Institute.

Source:

University of Pennsylvania

Media Contacts:

Hannah Messinger – University of Pennsylvania

Image Source:

The image is credited to Penn Medicine.

Original Research: Open access

“Behavioural and Neural Responses to Facial Disfigurement”. Franziska Hartung, Anja Jamrozik, Miriam E. Rosen, Geoffrey Aguirre, David B. Sarwer & Anjan Chatterjee.

Scientific Reports. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44408-8

Abstract

Behavioural and Neural Responses to Facial Disfigurement

Faces are among the most salient and relevant visual and social stimuli that humans encounter. Attractive faces are associated with positive character traits and social skills and automatically evoke larger neural responses than faces of average attractiveness in ventral occipito-temporal cortical areas. Little is known about the behavioral and neural responses to disfigured faces. In two experiments, we tested the hypotheses that people harbor a disfigured is bad bias and that ventral visual neural responses, known to be amplified to attractive faces, represent an attentional effect to facial salience rather than to their rewarding properties. In our behavioral study (N = 79), we confirmed the existence of an implicit ‘disfigured is bad’ bias. In our functional MRI experiment (N = 31), neural responses to photographs of disfigured faces before treatment evoked greater neural responses within ventral occipito-temporal cortex and diminished responses within anterior cingulate cortex. The occipito-temporal activity supports the hypothesis that these areas are sensitive to attentional, rather than reward properties of faces. The relative deactivation in anterior cingulate cortex, informed by our behavioral study, may reflect suppressed empathy and social cognition and indicate evidence of a possible neural mechanism underlying dehumanization.