Summary: A mere 1% reduction in deep sleep yearly for those above 60 translates to a 27% higher dementia risk.

Monitoring 346 participants over 60 from the Framingham Heart Study, the research observed declining deep sleep patterns and found 52 dementia cases in 17 years.

The importance of deep sleep lies in its potential role in clearing metabolic waste from the brain.

Thus, maintaining or boosting deep sleep in our senior years might be crucial to staving off dementia.

Key Facts:

- A 1% annual reduction in deep sleep for people over 60 corresponds to a 27% increased dementia risk.

- Of the study’s participants, over 17 years of follow-up, 52 cases of dementia were identified.

- Deep sleep aids in clearing metabolic waste, including proteins linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

Source: Monash University

As little as 1 percent reduction in deep sleep per year for people over 60 years of age translates into a 27 percent increased risk of dementia, according to a study which suggests that enhancing or maintaining deep sleep, also known as slow wave sleep, in older years could stave off dementia.

The study, led by Associate Professor Matthew Pase, from the Monash School of Psychological Sciences and the Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health in Melbourne, Australia, and published today in JAMA Neurology, looked at 346 participants, over 60 years of age, enrolled in the Framingham Heart Study who completed two overnight sleep studies in the time periods 1995 to 1998 and 2001 to 2003, with an average of five years between the two studies.

These participants were then carefully followed for dementia from the time of the second sleep study through to 2018. The researchers found, on average, that the amount of deep sleep declined between the two studies, indicating slow wave sleep loss with aging.

Over the next 17 years of follow-up, there were 52 cases of dementia. Even adjusting for age, sex, cohort, genetic factors, smoking status, sleeping medication use, antidepressant use, and anxiolytic use, each percentage decrease in deep sleep each year was associated with a 27 percent increase in the risk of dementia.

“Slow-wave sleep, or deep sleep, supports the aging brain in many ways, and we know that sleep augments the clearance of metabolic waste from the brain, including facilitating the clearance of proteins that aggregate in Alzheimer’s disease,” Associate Professor Pase said.

“However, to date we have been unsure of the role of slow-wave sleep in the development of dementia. Our findings suggest that slow wave sleep loss may be a modifiable dementia risk factor.”

Associate Professor Pase said that the Framingham Heart Study is a unique community-based cohort with repeated overnight polysomnographic (PSG) sleep studies and uninterrupted surveillance for incident dementia.

“We used these to examine how slow-wave sleep changed with aging and whether changes in slow-wave sleep percentage were associated with the risk of later-life dementia up to 17 years later,” he said.

“We also examined whether genetic risk for Alzheimer’s Disease or brain volumes suggestive of early neurodegeneration were associated with a reduction in slow-wave sleep. We found that a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, but not brain volume, was associated with accelerated declines in slow wave sleep.”

About this sleep and dementia research news

Author: Tania Ewing

Source: Monash University

Contact: Tania Ewing – Monash University

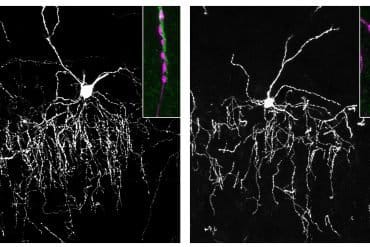

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Closed access.

“Association Between Slow-Wave Sleep Loss and Incident Dementia” by Matthew Pase et al. JAMA Neurology

Abstract

Association Between Slow-Wave Sleep Loss and Incident Dementia

Importance

Slow-wave sleep (SWS) supports the aging brain in many ways, including facilitating the glymphatic clearance of proteins that aggregate in Alzheimer disease. However, the role of SWS in the development of dementia remains equivocal.

Objective

To determine whether SWS loss with aging is associated with the risk of incident dementia and examine whether Alzheimer disease genetic risk or hippocampal volumes suggestive of early neurodegeneration were associated with SWS loss.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective cohort study included participants in the Framingham Heart Study who completed 2 overnight polysomnography (PSG) studies in the time periods 1995 to 1998 and 1998 to 2001. Additional criteria for individuals in this study sample were an age of 60 years or older and no dementia at the time of the second overnight PSG. Data analysis was performed from January 2020 to August 2023.

Exposure

Changes in SWS percentage measured across repeated overnight sleep studies over a mean of 5.2 years apart (range, 4.8-7.1 years).

Main Outcome

Risk of incident all-cause dementia adjudicated over 17 years of follow-up from the second PSG.

Results

From the 868 Framingham Heart Study participants who returned for a second PSG, this cohort included 346 participants with a mean age of 69 years (range, 60-87 years); 179 (52%) were female. Aging was associated with SWS loss across repeated overnight sleep studies (mean [SD] change, −0.6 [1.5%] per year; P < .001). Over the next 17 years of follow-up, there were 52 cases of incident dementia. In Cox regression models adjusted for age, sex, cohort, positivity for at least 1 APOE ε4 allele, smoking status, sleeping medication use, antidepressant use, and anxiolytic use, each percentage decrease in SWS per year was associated with a 27% increase in the risk of dementia (hazard ratio, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.06-1.54; P = .01). SWS loss with aging was accelerated in the presence of Alzheimer disease genetic risk (ie, APOE ε4 allele) but not hippocampal volumes measured proximal to the first PSG.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study found that slow-wave sleep percentage declined with aging and Alzheimer disease genetic risk, with greater reductions associated with the risk of incident dementia. These findings suggest that SWS loss may be a modifiable dementia risk factor.