Summary: Higher levels of critical thinking is associated with lower levels of dogmatism in both the religious and non-religious. Those who are most dogmatic are less likely to be able to look at issues from the perspective of others, a new study reports.

Source: Case Western Reserve.

Insight suggests ways to communicate with people who ignore evidence that contradicts cherished beliefs.

Dogmatic individuals hold confidently to their beliefs, even when experts disagree and evidence contradicts them. New research from Case Western Reserve University may help explain the extreme perspectives, on religion, politics and more, that seem increasingly prevalent in society.

Two studies examine the personality characteristics that drive dogmatism in the religious and nonreligious. They show there are both similarities and important differences in what drives dogmatism in these two groups.

In both groups, higher critical reasoning skills were associated with lower levels of dogmatism. But these two groups diverge in how moral concern influences their dogmatic thinking.

“It suggests that religious individuals may cling to certain beliefs, especially those which seem at odds with analytic reasoning, because those beliefs resonate with their moral sentiments,” said Jared Friedman, a PhD student in organizational behavior and co-author of the studies.

“Emotional resonance helps religious people to feel more certain–the more moral correctness they see in something, the more it affirms their thinking,” said Anthony Jack, associate professor of philosophy and co-author of the research. “In contrast, moral concerns make nonreligious people feel less certain.”

This understanding may suggest a way to effectively communicate with the extremes, the researchers say. Appealing to a religious dogmatist’s sense of moral concern and to an anti-religious dogmatist’s unemotional logic may increase the chances of getting a message through–or at least some consideration from them.

The research is published in the Journal of Religion and Health.

Extreme positions

While more empathy may sound desirable, untempered empathy can be dangerous, Jack said. “Terrorists, within their bubble, believe it’s a highly moral thing they’re doing. They believe they are righting wrongs and protecting something sacred.”

In today’s politics, Jack said, “with all this talk about fake news, the Trump administration, by emotionally resonating with people, appeals to members of its base while ignoring facts.” Trump’s base includes a large percentage of self-declared religious men and women.

At the other extreme, despite organizing their life around critical thinking, militant atheists, “may lack the insight to see anything positive about religion; they can only see that it contradicts their scientific, analytical thinking,” Jack said.

The studies, based on surveys of more than 900 people, also found some similarities between religious and non-religious people. In both groups the most dogmatic are less adept at analytical thinking, and also less likely to look at issues from other’s perspectives.

In the first study, 209 participants identified as Christian, 153 as nonreligious, nine Jewish, five Buddhist, four Hindu, one Muslim and 24 another religion. Each completed tests assessing dogmatism, empathetic concern, aspects of analytical reasoning, and prosocial intentions.

The results showed religious participants as a whole had a higher level of dogmatism, empathetic concern and prosocial intentions, while the nonreligious performed better on the measure of analytic reasoning. Decreasing empathy among the nonreligious corresponded to increasing dogmatism.

The second study, which included 210 participants who identified as Christian, 202 nonreligious, 63 Hindu, 12 Buddhist, 11 Jewish, 10 Muslim and 19 other religions, repeated much of the first but added measures of perspective-taking and religious fundamentalism.

The more rigid the individual, whether religious or not, the less likely he or she would consider the perspective of others. Religious fundamentalism was highly correlated with empathetic concern among the religious.

Two brain networks

The researchers say the results of the surveys lend further support to their earlier work showing people have two brain networks–one for empathy and one for analytic thinking – that are in tension with each other. In healthy people, their thought process cycles between the two, choosing the appropriate network for different issues they consider.

But in the religious dogmatist’s mind, the empathetic network appears to dominate while in the nonreligious dogmatist’s mind, the analytic network appears to rule.

While the studies examined how differences in worldview of the religious vs. the nonreligious influence dogmatism, the research is broadly applicable, the researchers say. Dogmatism applies to any core beliefs, from eating habits –whether to be a vegan, vegetarian or omnivore– to political opinions and beliefs about evolution and climate change. The authors hope this and further research will help improve the divide in opinions that seems increasingly prevalent.

Source: William Lubinger – Case Western Reserve

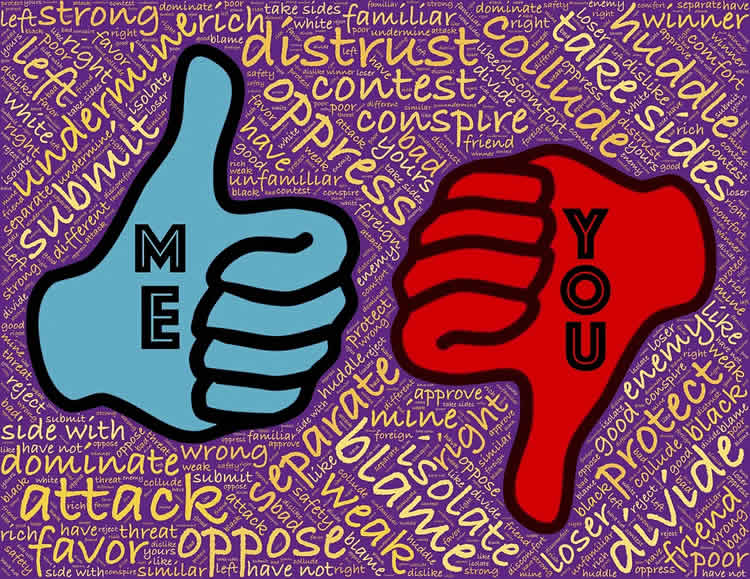

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is adapted from the Case Western Reserve news release.

Original Research: Abstract for “What Makes You So Sure? Dogmatism, Fundamentalism, Analytic Thinking, Perspective Taking and Moral Concern in the Religious and Nonreligious” by Jared Parker Friedman and Anthony Ian Jack in Journal of Religion and Health. Published online June 10 2017 doi:10.1007/s10943-017-0433-x

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Case Western Reserve “Studies Help Understand Why Some People Are So Sure They’re Right.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 26 July 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/belief-right-psychology-7183/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Case Western Reserve (2017, July 26). Studies Help Understand Why Some People Are So Sure They’re Right. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved July 26, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/belief-right-psychology-7183/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Case Western Reserve “Studies Help Understand Why Some People Are So Sure They’re Right.” https://neurosciencenews.com/belief-right-psychology-7183/ (accessed July 26, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

What Makes You So Sure? Dogmatism, Fundamentalism, Analytic Thinking, Perspective Taking and Moral Concern in the Religious and Nonreligious

Better understanding the psychological factors related to certainty in one’s beliefs (i.e., dogmatism) has important consequences for both individuals and social groups. Generally, beliefs can find support from at least two different routes of information processing: social/moral considerations or analytic/empirical reasoning. Here, we investigate how these two psychological constructs relate to dogmatism in two groups of individuals who preferentially draw on the former or latter sort of information when forming beliefs about the world—religious and nonreligious individuals. Across two studies and their pooled analysis, we provide evidence that although dogmatism is negatively related to analytic reasoning in both groups of individuals, it shares a divergent relationship with measures of moral concern depending on whether one identifies as religious or not. Study 1 showed that increasing levels of dogmatism were positively related to prosocial intentions among the religious and negatively related to empathic concern among the nonreligious. Study 2 replicated and extended these results by showing that perspective taking is negatively related to dogmatism in both groups, an effect which is particularly robust among the nonreligious. Study 2 also showed that religious fundamentalism was positively related to measures of moral concern among the religious. Because the current studies used a content-neutral measure to assess dogmatic certainty in one’s beliefs, they have the potential to inform practices for most effectively communicating with and persuading religious and nonreligious individuals to change maladaptive behavior, even when the mode of discourse is unrelated to religious belief.

“What Makes You So Sure? Dogmatism, Fundamentalism, Analytic Thinking, Perspective Taking and Moral Concern in the Religious and Nonreligious” by Jared Parker Friedman and Anthony Ian Jack in Journal of Religion and Health. Published online June 10 2017 doi:10.1007/s10943-017-0433-x