Summary: A new study identifies specific brain network hotspots linked to autism, aggression, and a range of other social behavioral problems. The findings reveal those with ASD who score lower on facial processing tests are more likely to have more severe symptoms of autism, especially social behavioral problems. The researchers report treatments such as tRMS may provide some hope for those on the autism spectrum.

Source: Children’s Hospital Boston

What if doctors could break down conditions like autism into their key symptoms, map these symptoms to “hotspots” in the brain, and then treat those areas directly with brain stimulation? If it bears out, such an approach could turn the care of neurologic and developmental disorders on its head, focusing on symptoms that are shared across multiple conditions.

That’s the vision of Dr. Alexander Li Cohen, a child neurologist and researcher who leads the Laboratory of Translational Neuroimaging and is part of the Autism Spectrum Center at Boston Children’s. “What we’ve seen is that individual parts of human behavior map onto different brain networks,” he says.

Face blindness: A window into understanding autism

Dr. Cohen began by studying a common problem in autism: face blindness, or the inability to recognize faces—even faces of loved ones. Studying people with autism spectrum disorder, he had found that those who scored poorly on tests of face processing had more severe symptoms, especially social impairments. Could understanding face blindness provide a way to understand autism?

To answer this question, he first studied people who developed face blindness after a stroke. Analyzing their brain MRIs, he found that many had damage in a location known as the fusiform face area. Others had no direct damage there, but did have damage to parts of the brain that connect to that area, as shown by a technique called lesion network mapping.

“It may take a whole brain network to cause a symptom,” Dr. Cohen explains.

Tuberous sclerosis, the fusiform face area, and autism

To begin to connect the dots to autism, he next studied patients with tuberous sclerosis. In this rare genetic condition, abnormal growths called tubers form in the brain and other organs. Forty percent of affected children go on to develop autism.

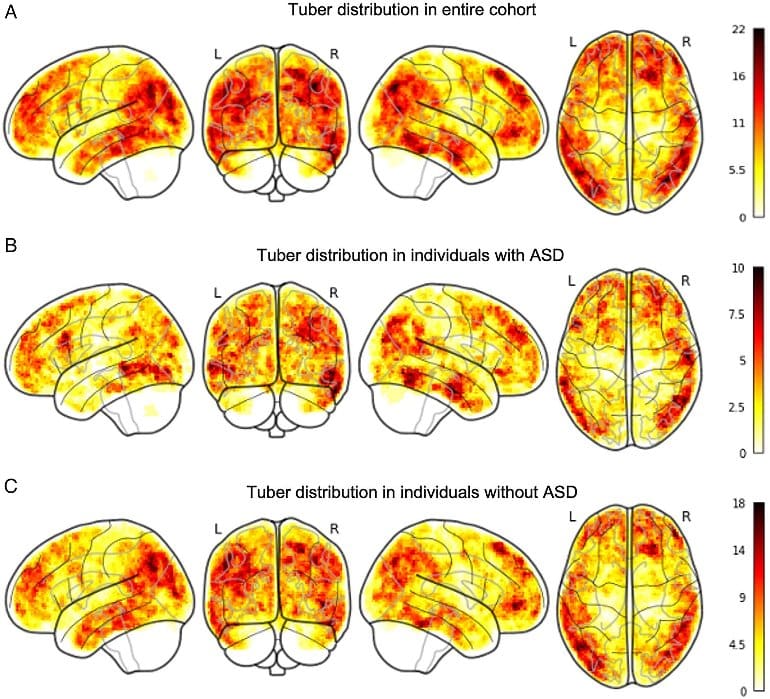

“I was curious to understand whether the pattern of tubers in the brain influences the chance of developing autism,” Dr. Cohen says.

Indeed it did. In an analysis of 115 young children with tuberous sclerosis, he found that those with tubers at or near the fusiform face area were 3.7 times more likely to develop autism. The study is published in the journal Annals of Neurology.

Dr. Cohen now wants to see whether children with autism who don’t have tuberous sclerosis have abnormalities in this area or in brain networks connected to it. To that end, he and his colleagues have begun recruiting teens age 15 to 18 for a study comparing brain MRIs from those with and without autism. The team is assessing each participant for face processing ability, social impairment, and autism symptom severity to see how these correlate with brain imaging findings.

Brain stimulation for autism?

Could differences in face processing cause autism, or do they result from autism? That’s another question Dr. Cohen hopes to answer. He suspects that people with autism may rely too much on a particular brain network to process faces, perhaps one focused on small details rather than faces as a whole.

“That is something that kids with autism can have a lot of difficulty with,” he says.

If face blindness could be treated in children with autism, would it also improve their social functioning? “Now that we’ve started looking at autism directly, we’ll see what we can figure out.”

Dr. Cohen envisions noninvasive treatments like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), in which a small electromagnet induces currents on the surface of the brain, in targeted locations. TMS has been found safe and is approved for treating depression and obsessive compulsive disorder in adults. Boston Children’s researchers are currently testing it in some children with epilepsy who cannot be effectively treated with drugs or surgery.

Addressing agitation and aggression, in autism and beyond

Ultimately, Dr. Cohen wants to identify brain hotspots and networks that drive a variety of autism symptoms and behaviors, not just face processing. At the top of his list are aggression and agitation, which can create difficult situations for children with autism and their families. Today, they are often treated with medications originally meant for psychosis, which have significant side effects and don’t always work.

Dr. Cohen hopes a new study will help change this. He and his colleagues are tapping brain mapping data from a variety of groups who are at risk for developing aggressive behaviors, including people with autism, people who have had a stroke, and people with other forms of brain injury, looking for aggression “hotspots.” To date, they have gathered data from more than 1,200 children and adults.

“You can sort people by the most versus the least aggression and ask, ‘What in the brain is different?'” Dr. Cohen explains.

“We can try to find what those with aggression have in common and see if there’s something we could turn into a treatment target. If we can nip some of these symptoms in the bud early on, we might be able to help the brain move onto a different path.”

About this autism research news

Author: Nancy Fliesler

Source: Children’s Hospital Boston

Contact: Nancy Fliesler – Children’s Hospital Boston

Image: The image is credited to Annals of Neurology/ The Researchers

Original Research: Open access.

“Tubers Affecting the Fusiform Face Area Are Associated with Autism Diagnosis” by Alexander Li Cohen et al. Annals of Neurology

Abstract

Tubers Affecting the Fusiform Face Area Are Associated with Autism Diagnosis

Objective

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is associated with focal brain “tubers” and a high incidence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The location of brain tubers associated with autism may provide insight into the neuroanatomical substrate of ASD symptoms.

Methods

We delineated tuber locations for 115 TSC participants with ASD (n = 31) and without ASD (n = 84) from the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Autism Center of Excellence Research Network. We tested for associations between ASD diagnosis and tuber burden within the whole brain, specific lobes, and at 8 regions of interest derived from the ASD neuroimaging literature, including the anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal and posterior parietal cortices, inferior frontal and fusiform gyri, superior temporal sulcus, amygdala, and supplemental motor area. Next, we performed an unbiased data-driven voxelwise lesion symptom mapping (VLSM) analysis. Finally, we calculated the risk of ASD associated with positive findings from the above analyses.

Results

There were no significant ASD-related differences in tuber burden across the whole brain, within specific lobes, or within a priori regions derived from the ASD literature. However, using VLSM analysis, we found that tubers involving the right fusiform face area (FFA) were associated with a 3.7-fold increased risk of developing ASD.

Interpretation

Although TSC is a rare cause of ASD, there is a strong association between tuber involvement of the right FFA and ASD diagnosis. This highlights a potentially causative mechanism for developing autism in TSC that may guide research into ASD symptoms more generally. ANN NEUROL 2023;93:577–590