By studying stroke victims who have lost the ability to spell, researchers have pinpointed the parts of the brain that control how we write words.

In the latest issue of the journal Brain, Johns Hopkins University neuroscientists link basic spelling difficulties for the first time with damage to seemingly unrelated regions of the brain, shedding new light on the mechanics of language and memory.

“When something goes wrong with spelling, it’s not one thing that always happens — different things can happen and they come from different breakdowns in the brain’s machinery,” said lead author Brenda Rapp, a professor in the Department of Cognitive Sciences. “Depending on what part breaks, you’ll have different symptoms.”

Rapp’s team studied 15 years’ worth of cases in which 33 people were left with spelling impairments after suffering strokes. Some of the people had long-term memory difficulties, others working-memory issues.

With long-term memory difficulties, people can’t remember how to spell words they once knew and tend to make educated guesses. They could probably correctly guess a predictably spelled word like “camp,” but with a more unpredictable spelling like “sauce,” they might try “soss.” In severe cases, people trying to spell “lion” might offer things like “lonp,” “lint” and even “tiger.” With working memory issues, people know how to spell words but they have trouble choosing the correct letters or assembling the letters in the correct order — “lion” might be “liot,” “lin,” “lino,” or “liont.”

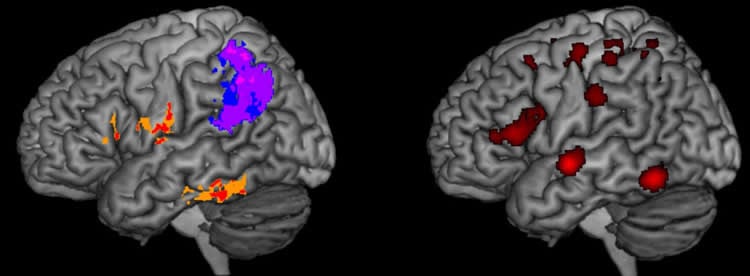

The team used computer mapping to chart the brain lesions of each individual and found that in the long-term memory cases, damage appeared on two areas of the left hemisphere, one towards the front of the brain and the other at the lower part of the brain towards the back. In working memory cases, the lesions were primarily also in the left hemisphere but in a very different area in the upper part of the brain towards the back.

“I was surprised to see how distant and distinct the brain regions are that support these two subcomponents of the writing process, especially two subcomponents that are so closely inter-related during spelling that some have argued that they shouldn’t be thought of as separate functions,” Rapp said. “You might have thought that they would be closer together and harder to tease apart.”

Though science knows quite a bit about how the brain handles reading, these findings offer some of the first clear evidence of how it spells, an understanding that could lead to improved behavioral treatments after brain damage and more effective ways to teach spelling.

Rapp’s co-authors are Johns Hopkins postdoctoral fellow Jeremy Purcell; School of Medicine professor Argye E. Hillis; Rita Capasso of S.C.A. Associates in Rome, Italy; and Gabriele Miceli, a professor at University of Trento, Italy.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DC012283 and DC05375.

Source: Jill Rosen – Johns Hopkins University

Image Source: The image is credited to the researchers/University of Southampton

Original Research: Full open access research for “Neural bases of orthographic long-term memory and working memory in dysgraphia” by Brenda Rapp, Jeremy Purcell, Argye E. Hillis, Rita Capasso, and Gabriele Miceli in Brain. Published online December 17 2015 doi:10.1093/brain/awv348

Abstract

Neural bases of orthographic long-term memory and working memory in dysgraphia

Spelling a word involves the retrieval of information about the word’s letters and their order from long-term memory as well as the maintenance and processing of this information by working memory in preparation for serial production by the motor system. While it is known that brain lesions may selectively affect orthographic long-term memory and working memory processes, relatively little is known about the neurotopographic distribution of the substrates that support these cognitive processes, or the lesions that give rise to the distinct forms of dysgraphia that affect these cognitive processes. To examine these issues, this study uses a voxel-based mapping approach to analyse the lesion distribution of 27 individuals with dysgraphia subsequent to stroke, who were identified on the basis of their behavioural profiles alone, as suffering from deficits only affecting either orthographic long-term or working memory, as well as six other individuals with deficits affecting both sets of processes. The findings provide, for the first time, clear evidence of substrates that selectively support orthographic long-term and working memory processes, with orthographic long-term memory deficits centred in either the left posterior inferior frontal region or left ventral temporal cortex, and orthographic working memory deficits primarily arising from lesions of the left parietal cortex centred on the intraparietal sulcus. These findings also contribute to our understanding of the relationship between the neural instantiation of written language processes and spoken language, working memory and other cognitive skills.

“Neural bases of orthographic long-term memory and working memory in dysgraphia” by Brenda Rapp, Jeremy Purcell, Argye E. Hillis, Rita Capasso, and Gabriele Miceli in Brain. Published online December 17 2015 doi:10.1093/brain/awv348