Researchers from Imperial College London, working with the Beckley Foundation, have for the first time visualised the effects of LSD on the human brain.

In a series of experiments, scientists have gained a glimpse into how the psychedelic compound affects brain activity. The team administered LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide) to 20 healthy volunteers in a specialist research centre and used various leading-edge and complementary brain scanning techniques to visualise how LSD alters the way the brain works.

The findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), reveal what happens in the brain when people experience the complex visual hallucinations that are often associated with LSD state. They also shed light on the brain changes that underlie the profound altered state of consciousness the drug can produce.

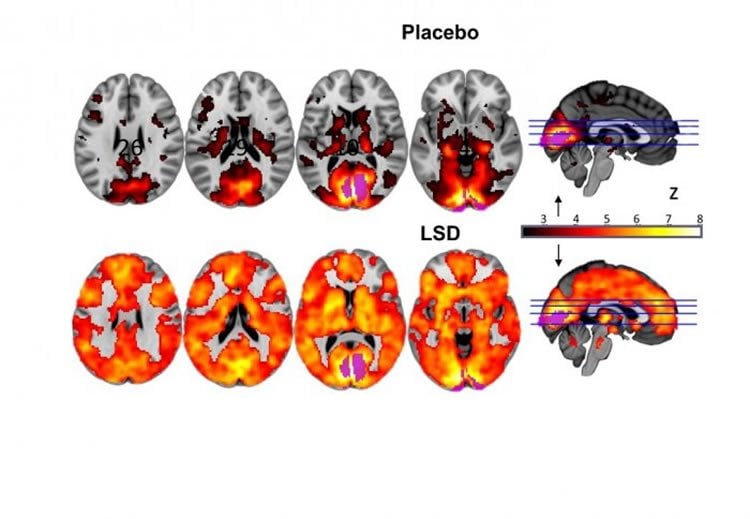

A major finding of the research is the discovery of what happens in the brain when people experience complex dreamlike hallucinations under LSD. Under normal conditions, information from our eyes is processed in a part of the brain at the back of the head called the visual cortex. However, when the volunteers took LSD, many additional brain areas – not just the visual cortex – contributed to visual processing.

Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, from the Department of Medicine at Imperial, who led the research, explained: “We observed brain changes under LSD that suggested our volunteers were ‘seeing with their eyes shut’ – albeit they were seeing things from their imagination rather than from the outside world. We saw that many more areas of the brain than normal were contributing to visual processing under LSD – even though the volunteers’ eyes were closed. Furthermore, the size of this effect correlated with volunteers’ ratings of complex, dreamlike visions. ”

The study also revealed what happens in the brain when people report a fundamental change in the quality of their consciousness under LSD.

Dr Carhart-Harris explained: “Normally our brain consists of independent networks that perform separate specialised functions, such as vision, movement and hearing – as well as more complex things like attention. However, under LSD the separateness of these networks breaks down and instead you see a more integrated or unified brain.

“Our results suggest that this effect underlies the profound altered state of consciousness that people often describe during an LSD experience. It is also related to what people sometimes call ‘ego-dissolution’, which means the normal sense of self is broken down and replaced by a sense of reconnection with themselves, others and the natural world. This experience is sometimes framed in a religious or spiritual way – and seems to be associated with improvements in well-being after the drug’s effects have subsided.”

Dr Carhart-Harris added: “Our brains become more constrained and compartmentalised as we develop from infancy into adulthood, and we may become more focused and rigid in our thinking as we mature. In many ways, the brain in the LSD state resembles the state our brains were in when we were infants: free and unconstrained. This also makes sense when we consider the hyper-emotional and imaginative nature of an infant’s mind.”

In addition to these findings, research from the same group, part of the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme, revealed that listening to music while taking LSD triggered interesting changes in brain signalling that were associated with eyes-closed visions.

In a study published in the journal European Neuropsychopharmacology, the researchers found altered visual cortex activity under the drug, and that the combination of LSD and music caused this region to receive more information from an area of the brain called the parahippocampus. The parahippocampus is involved in mental imagery and personal memory, and the more it communicated with the visual cortex, the more people reported experiencing complex visions, such as seeing scenes from their lives.

PhD student Mendel Kaelen from the Department of Medicine at Imperial, who was lead author of the music paper, said: “This is the first time we have witnessed the interaction of a psychedelic compound and music with the brain’s biology.

The Beckley/Imperial Research Programme hope these collective findings may pave the way for these compounds being one day used to treat psychiatric disorders. They could be particularly useful in conditions where negative thought patterns have become entrenched, say the scientists, such as in depression or addiction.

Mendel Kaelen added: “A major focus for future research is how we can use the knowledge gained from our current research to develop more effective therapeutic approaches for treatments such as depression; for example, music-listening and LSD may be a powerful therapeutic combination if provided in the right way.”

under LSD, which was linked to hallucinations. Image adapted from the Imperial College press release.

Professor David Nutt, the senior researcher on the study and Edmond J Safra Chair in Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial, said: “Scientists have waited 50 years for this moment – the revealing of how LSD alters our brain biology. For the first time we can really see what’s happening in the brain during the psychedelic state, and can better understand why LSD had such a profound impact on self-awareness in users and on music and art. This could have great implications for psychiatry, and helping patients overcome conditions such as depression.”

Amanda Feilding, Director of the Beckley Foundation, said: “We are finally unveiling the brain mechanisms underlying the potential of LSD, not only to heal, but also to deepen our understanding of consciousness itself.”

The research involved 20 healthy volunteers – each of whom received both LSD and placebo – and all of whom were deemed psychologically and physically healthy. All the volunteers had previously taken some type of psychedelic drug. During carefully controlled and supervised experiments in a specialist research centre, each volunteer received an injection of either 75 micrograms of LSD, or placebo. Their brains were then scanned using various techniques including fMRI and magnetoencephalography (MEG). These enabled the researchers to study activity within the whole of the brain by monitoring blood flow and electrical activity.

Source: Kate Wighton – Imperial College London

Image Source: The image adapted from the Imperial College press release.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging” by Robin L. Carhart-Harris, Suresh Muthukumaraswamy, Leor Roseman, Mendel Kaelen, Wouter Droog, Kevin Murphy, Enzo Tagliazucchi, Eduardo E. Schenberg, Timothy Nest, Csaba Orban, Robert Leech, Luke T. Williams, Tim M. Williams, Mark Bolstridge, Ben Sessa, John McGonigle, Martin I. Sereno, David Nichols, Peter J. Hellyer, Peter Hobden, John Evans, Krish D. Singh, Richard G. Wise, H. Valerie Curran, Amanda Feilding, and David J. Nutt in PNAS. Published online Aprill 11 2016 doi:10.1073/pnas.1518377113

Abstract

Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is the prototypical psychedelic drug, but its effects on the human brain have never been studied before with modern neuroimaging. Here, three complementary neuroimaging techniques: arterial spin labeling (ASL), blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) measures, and magnetoencephalography (MEG), implemented during resting state conditions, revealed marked changes in brain activity after LSD that correlated strongly with its characteristic psychological effects. Increased visual cortex cerebral blood flow (CBF), decreased visual cortex alpha power, and a greatly expanded primary visual cortex (V1) functional connectivity profile correlated strongly with ratings of visual hallucinations, implying that intrinsic brain activity exerts greater influence on visual processing in the psychedelic state, thereby defining its hallucinatory quality. LSD’s marked effects on the visual cortex did not significantly correlate with the drug’s other characteristic effects on consciousness, however. Rather, decreased connectivity between the parahippocampus and retrosplenial cortex (RSC) correlated strongly with ratings of “ego-dissolution” and “altered meaning,” implying the importance of this particular circuit for the maintenance of “self” or “ego” and its processing of “meaning.” Strong relationships were also found between the different imaging metrics, enabling firmer inferences to be made about their functional significance. This uniquely comprehensive examination of the LSD state represents an important advance in scientific research with psychedelic drugs at a time of growing interest in their scientific and therapeutic value. The present results contribute important new insights into the characteristic hallucinatory and consciousness-altering properties of psychedelics that inform on how they can model certain pathological states and potentially treat others.

“Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging” by Robin L. Carhart-Harris, Suresh Muthukumaraswamy, Leor Roseman, Mendel Kaelen, Wouter Droog, Kevin Murphy, Enzo Tagliazucchi, Eduardo E. Schenberg, Timothy Nest, Csaba Orban, Robert Leech, Luke T. Williams, Tim M. Williams, Mark Bolstridge, Ben Sessa, John McGonigle, Martin I. Sereno, David Nichols, Peter J. Hellyer, Peter Hobden, John Evans, Krish D. Singh, Richard G. Wise, H. Valerie Curran, Amanda Feilding, and David J. Nutt in PNAS. Published online Aprill 11 2016 doi:10.1073/pnas.1518377113