Gut enzymes in sweet taste cells may point way to better-tasting non-caloric sweeteners.

According to new research from the Monell Center and collaborating institutions, the sweet taste cells that respond to sugars and sweeteners on the tongue also contain digestive enzymes capable of converting sucrose (table sugar) into glucose and fructose, simple sugars that can be detected by both known sweet taste pathways. The findings increase understanding of the complex cellular mechanisms underlying sweet taste detection.

“Through these insights we are better able to understand how sweet taste works, why sucrose is so appealing, and even perhaps what would be needed to make a sucrose substitute that tastes good but has no calories,” said study senior author Robert F. Margolskee, MD, PhD, a molecular neurobiologist at Monell.

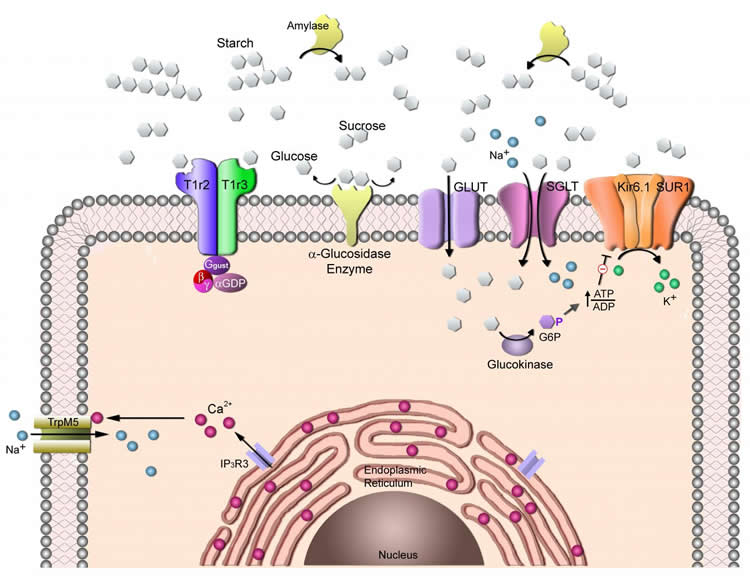

A sweet taste receptor called T1R2+T1R3 is the primary mechanism that enables taste cells to detect many different types of sweet compounds, including sucrose and other caloric sugars as well as non-caloric sweeteners such as saccharin and sucralose. However, mice with inactivated T1R2+T1R3 sweet receptors, called T1R3 knockout mice, still are able to sense glucose, sucrose and other caloric sugars, suggesting the existence of additional sweet receptors.

In 2011, Margolskee’s team used knowledge of sugar sensors in the intestine and pancreas to identify a second class of sweet taste sensors on the tongue. These ‘secondary’ sensors are sensitive to simple sugars like glucose but not to sucrose (glucose + fructose) and other complex food-related sugars. Thus, the researchers still needed to explain how the T1R3 knockout mice are able to sense sucrose.

In the present study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the taste researchers once again turned to the intestines for an answer. Knowing that gut enzymes break down complex sugars into simple sugars that can be absorbed into the bloodstream, the research team asked whether these same enzymes could also be breaking down sucrose and other complex sugars on the tongue.

“It makes sense that the tongue and gut would share similar pathways, as both detect ingested chemicals that are important for metabolic energy,” said study author Karen Yee, PhD, a cellular physiologist who co-led the research with molecular biologist Sunil K. Sukumaran, PhD. Both scientists are from Monell.

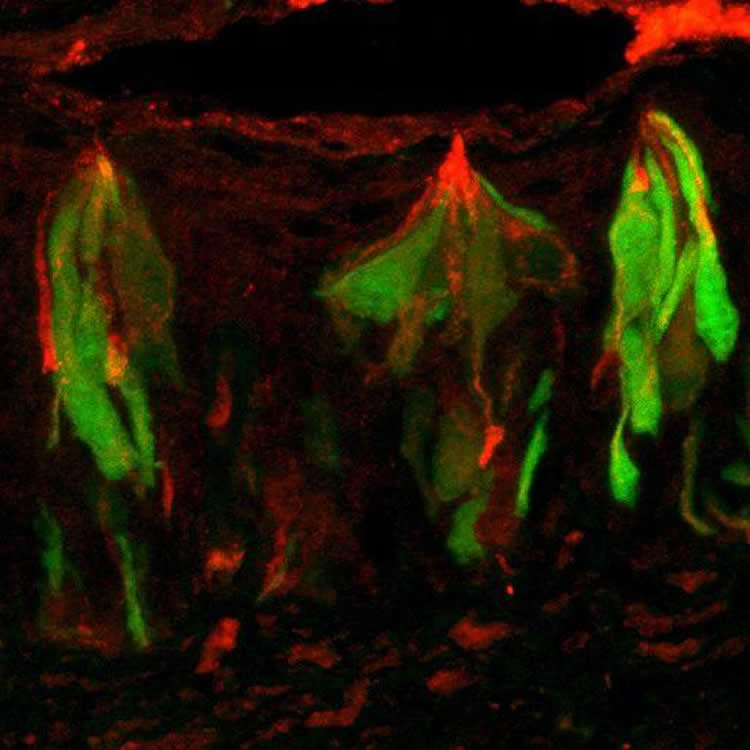

Using a mouse model, the researchers found that the intestinal digestive enzymes sucrase and maltase are also expressed in sweet taste cells on the tongue. The tongue enzymes are in the ideal location to cleave complex sugars from ingested foods into glucose and fructose, which can then activate the secondary sugar sensors.

Noting that the T1R2+T1R3 sweet receptor senses a range of molecules that includes non-caloric sweeteners, the authors speculate that the second sugar sensor pathway serves as a calorie detector for metabolizable sugars. Working together, the two sweet pathways can identify sweet substances with caloric value, providing a potential explanation for why humans and other mammals respond so positively to the taste of sucrose as opposed to non-caloric sweeteners.

“Sucrose is the perfect sweet compound. As a complex sugar, it activates the ‘classic’ main sweet receptor, but after being broken down by sucrase in the taste cells, the released glucose also activates the second sweet pathway,” said Margolskee.

The findings also have implications for the development of a new class of non-caloric sweeteners. Current non-caloric sweeteners, which only activate the T1R2+T1R3 receptor, are limited by their inability to replicate the full sweet taste of sugars. The researchers speculate this may be because existing non-caloric sweeteners do not target the secondary sugar sensors, which may mediate the unique sweet taste of sugar.

“A lot of effort is being put into developing strategies to limit sugar consumption, which leads to diseases such as diabetes and obesity. Our study potentially enlarges the arsenal to tackle them, especially because many pharmacological agents that target the secondary sugar sensors are already available,” said Sukumaran.

Moving forward, the researchers intend to explore if and how the second sugar sensor pathway contributes to sweet taste perception and perhaps regulation of sugar intake in humans.

Also contributing to the research were Monell scientist Ramana Kotha; Yuzo Ninomiya of Monell and Kyushu University; Shusuke Iwata and Noriatsu Shigemura of Kyushu University; Roberto Quezada-Calvillo of Baylor College of Medicine and Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi; Buford Nichols of Baylor College of Medicine; and Sankar Mohan and B. Mario Pinto of Simon Fraser University.

Funding: Research reported in the publication was supported by grants from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (DC03155, DC014105, and P30DC011735) of the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation (DBI-0216310), and by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science grants KAKENHI 15H02571, 26670810, 15K11044, and 25.4608. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other funding agencies.

Source: Leslie Stein – Monell Chemical Senses Center

Image Source: The images are credited to Karen Yee, Monell Center.

Original Research: Abstract for “Taste cell-expressed α-glucosidase enzymes contribute to gustatory responses to disaccharides” by Sunil K. Sukumaran, Karen K. Yee, Shusuke Iwata, Ramana Kotha, Roberto Quezada-Calvillo, Buford L. Nichols, Sankar Mohan, B. Mario Pinto, Noriatsu Shigemura, Yuzo Ninomiya, and Robert F. Margolskee in PNAS. Published online May 4 2016 doi:10.1073/pnas.1520843113

Abstract

Taste cell-expressed α-glucosidase enzymes contribute to gustatory responses to disaccharides

The primary sweet sensor in mammalian taste cells for sugars and noncaloric sweeteners is the heteromeric combination of type 1 taste receptors 2 and 3 (T1R2+T1R3, encoded by Tas1r2 and Tas1r3 genes). However, in the absence of T1R2+T1R3 (e.g., in Tas1r3 KO mice), animals still respond to sugars, arguing for the presence of T1R-independent detection mechanism(s). Our previous findings that several glucose transporters (GLUTs), sodium glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1), and the ATP-gated K+ (KATP) metabolic sensor are preferentially expressed in the same taste cells with T1R3 provides a potential explanation for the T1R-independent detection of sugars: sweet-responsive taste cells that respond to sugars and sweeteners may contain a T1R-dependent (T1R2+T1R3) sweet-sensing pathway for detecting sugars and noncaloric sweeteners, as well as a T1R-independent (GLUTs, SGLT1, KATP) pathway for detecting monosaccharides. However, the T1R-independent pathway would not explain responses to disaccharide and oligomeric sugars, such as sucrose, maltose, and maltotriose, which are not substrates for GLUTs or SGLT1. Using RT-PCR, quantitative PCR, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry, we found that taste cells express multiple α-glycosidases (e.g., amylase and neutral α glucosidase C) and so-called intestinal “brush border” disaccharide-hydrolyzing enzymes (e.g., maltase-glucoamylase and sucrase-isomaltase). Treating the tongue with inhibitors of disaccharidases specifically decreased gustatory nerve responses to disaccharides, but not to monosaccharides or noncaloric sweeteners, indicating that lingual disaccharidases are functional. These taste cell-expressed enzymes may locally break down dietary disaccharides and starch hydrolysis products into monosaccharides that could serve as substrates for the T1R-independent sugar sensing pathways.

“Taste cell-expressed α-glucosidase enzymes contribute to gustatory responses to disaccharides” by Sunil K. Sukumaran, Karen K. Yee, Shusuke Iwata, Ramana Kotha, Roberto Quezada-Calvillo, Buford L. Nichols, Sankar Mohan, B. Mario Pinto, Noriatsu Shigemura, Yuzo Ninomiya, and Robert F. Margolskee in PNAS. Published online May 4 2016 doi:10.1073/pnas.1520843113