For patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD), current behavioral and pharmaceutical treatments work about half the time. After weeks of investment in therapy, about half of patients will likely still suffer with symptoms of anxiety, and have little choice but to try again with something else. This trial-and-error process — inevitable due to an absence of tools to guide treatment selection — is time-consuming and expensive, and some patients eventually just give up.

But new MIT research suggests that it may be possible to do better than a coin toss when choosing psychiatric therapies for patients. The study, which performed brain scans on 38 SAD patients, found that these scans contain clues that indicate, with about 80 percent accuracy, which SAD patients will do well in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), an intervention designed to help patients change thinking patterns. Use of the scans to predict treatment outcomes improved predictions fivefold over use of a clinician’s assessment alone.

“Choice of therapy is like a wheel of chance,” says first author Susan Whitfield-Gabrieli, a research scientist in the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT. “We’re hoping to use brain imaging to help provide more reliable predictors of treatment response.”

The researchers used a form of brain imaging that scans patients in a state of rest. Resting-state images can be done quickly, in about 15 minutes, and reliably, since they don’t require patients to follow instructions, so they have the potential to be used in a clinical setting as a tool that helps doctors select the best treatments for patients.

“Knowing who to give which therapy to upfront would save time, money, and health care resources,” says Greg Siegle, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine who was not involved in this study. “This ability would be staggering to have at our disposal for the health care system.”

The findings are reported in the current issue of the journal Molecular Psychiatry. The work was carried out in the lab of principal investigator John Gabrieli, the Grover Hermann Professor of Health Sciences and Cognitive Neuroscience at MIT and a member of the McGovern Institute.

Common disorder

Social anxiety disorder affects approximately 6.8 percent of Americans, about 15 million individuals, and is the country’s third-most-common mental health disorder, according to the National Institutes of Mental Health. Its symptoms include extreme anxiety in social settings that can interfere with work and quality of life. Patients living with this disorder are also at higher risk of other psychiatric disorders, such as depression and substance abuse.

The study analyzed SAD patients from the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University and the Center for Anxiety and Traumatic Stress at Massachusetts General Hospital. The patients were scanned prior to participation in 12 weeks of group-based CBT. They also were evaluated using a behavioral assessment tool called the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) before and after CBT to determine who had improved.

In 2013, co-author Satrajit Ghosh, a principal research scientist at the McGovern Institute, studied task-based scans of this same group of patients. He and Whitfield-Gabrieli found that scans of patients’ brains as they responded to angry or neutral faces and emotional or neutral scenes predicted CBT outcomes.

“But task-based scans have downsides,” Whitfield-Gabrieli says: Behavioral differences among patients can affect performance. Also, task-based scans can only be used on patients who can follow a task, which excludes infants and some elderly or very ill patients.

Scanning the resting brain

So Whitfield-Gabrieli followed this earlier research with a study of the predictive power of resting-state imaging, which she and colleagues had also performed prior to CBT. During a resting-state scan, the patient just lies there. “That’s the beauty of it,” she says. “They’re just letting their minds wander.”

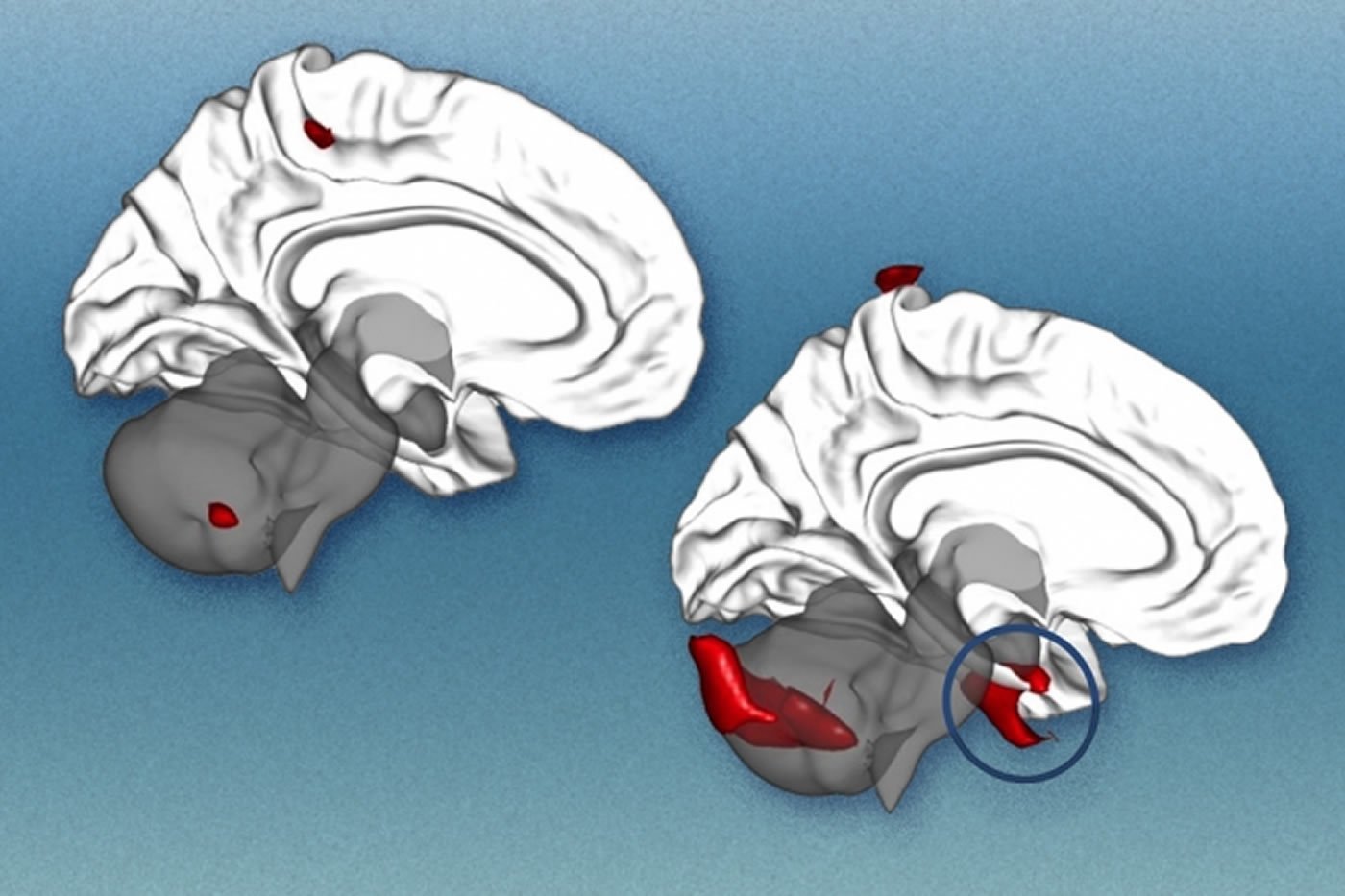

Resting-state imaging provides a look at the way a patient’s brain is wired, both structurally and functionally. For instance, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) shows which parts of the brain synchronize with one another during rest, suggesting that they are functionally connected. In addition, analysis of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) shows the underlying anatomy of the white matter tracts that interconnect distant brain regions.

Based on findings from their earlier research, Whitfield-Gabrieli and colleagues first used resting-state fMRI to look at connections to the amygdala, the seat of fear in the brain. They found that patients with higher connectivity to the amygdala from certain other regions were more likely to have lower anxiety after CBT.

They then performed a second analysis of the resting-state fMRI data, this time looking across the entire brain for patterns of connectivity. This analysis revealed additional markers that were predictive of treatment. The researchers also analyzed dMRI data and found that more robust connectivity in the tract that connects visual cues with emotional responses is also predictive of improvement with CBT.

Higher LSAS scores, which indicate more severe SAD, correlate modestly with larger improvements after CBT. In this study, each brain scan analysis had predictive value beyond the LSAS, and the three analyses together produced a fivefold improvement in predictive power over the LSAS alone.

The next step for Whitfield-Gabrieli and colleagues is to validate their predictive model on hundreds or possibly thousands of patients. Such a large-scale study may be possible because resting-state scans are comparable even when performed in different labs or by different researchers. Such comparisons weren’t feasible using task-based scans, which tend to vary from lab to lab.

“Right now there’s a huge movement to create massive data sets, to share resting-state imaging data, and really change the way people do science,” Whitfield-Gabrieli says.

Other next steps for Whitfield-Gabrieli’s group are studies to predict the success of more than one form of therapy, and to look at other psychiatric conditions, such as depression and attention disorders. “We don’t want to just know if they’re going to respond to one treatment,” she says. “We want to know which treatment is best for each patient.”

Funding: The National Institutes of Mental Health and the Poitras Center for Affective Disorders Research at MIT supported this work. Boston University computational neuroscientist Alfonso Nieto-Castanon and McGovern Institute postdoc Zeynep Saygin also contributed to this research.

Source: Elizabeth Dougherty – MIT

Image Source: The image is credited to Alfonso Nieto-Castañón and MIT News

Original Research: Abstract for “Brain connectomics predict response to treatment in social anxiety disorder” by S Whitfield-Gabrieli, S S Ghosh, A Nieto-Castanon, Z Saygin, O Doehrmann, X J Chai, G O Reynolds, S G Hofmann, M H Pollack and J D E Gabrieli in Molecular Psychiatry. Published online August 11 2015 doi:10.1038/mp.2015.109

Abstract

Brain connectomics predict response to treatment in social anxiety disorder

We asked whether brain connectomics can predict response to treatment for a neuropsychiatric disorder better than conventional clinical measures. Pre-treatment resting-state brain functional connectivity and diffusion-weighted structural connectivity were measured in 38 patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD) to predict subsequent treatment response to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). We used a priori bilateral anatomical amygdala seed-driven resting connectivity and probabilistic tractography of the right inferior longitudinal fasciculus together with a data-driven multivoxel pattern analysis of whole-brain resting-state connectivity before treatment to predict improvement in social anxiety after CBT. Each connectomic measure improved the prediction of individuals’ treatment outcomes significantly better than a clinical measure of initial severity, and combining the multimodal connectomics yielded a fivefold improvement in predicting treatment response. Generalization of the findings was supported by leave-one-out cross-validation. After dividing patients into better or worse responders, logistic regression of connectomic predictors and initial severity combined with leave-one-out cross-validation yielded a categorical prediction of clinical improvement with 81% accuracy, 84% sensitivity and 78% specificity. Connectomics of the human brain, measured by widely available imaging methods, may provide brain-based biomarkers (neuromarkers) supporting precision medicine that better guide patients with neuropsychiatric diseases to optimal available treatments, and thus translate basic neuroimaging into medical practice.

“Brain connectomics predict response to treatment in social anxiety disorder” by S Whitfield-Gabrieli, S S Ghosh, A Nieto-Castanon, Z Saygin, O Doehrmann, X J Chai, G O Reynolds, S G Hofmann, M H Pollack and J D E Gabrieli in Molecular Psychiatry. Published online August 11 2015 doi:10.1038/mp.2015.109