Summary: Researchers provide the first evidence that the human brain replays waking experiences while we sleep.

Source: Cell Press

When we fall asleep, our brains are not merely offline, they’re busy organizing new memories–and now, scientists have gotten a glimpse of the process. Researchers report in the journal Cell Reports on May 5 the first direct evidence that human brains replay waking experiences while asleep, seen in two participants with intracortical microelectrode arrays placed in their brains as part of a brain-computer interface pilot clinical trial.

During sleep, the brain replays neural firing patterns experienced while awake, also known as “offline replay.” Replay is thought to underlie memory consolidation, the process by which recent memories acquire more permanence in their neural representation. Scientists have previously observed replay in animals, but the study led by Jean-Baptiste Eichenlaub of Massachusetts General Hospital and Beata Jarosiewicz, formerly Research Assistant Professor at BrainGate, and now Senior Research Scientist at NeuroPace, tested whether the phenomenon happens in human brains as well.

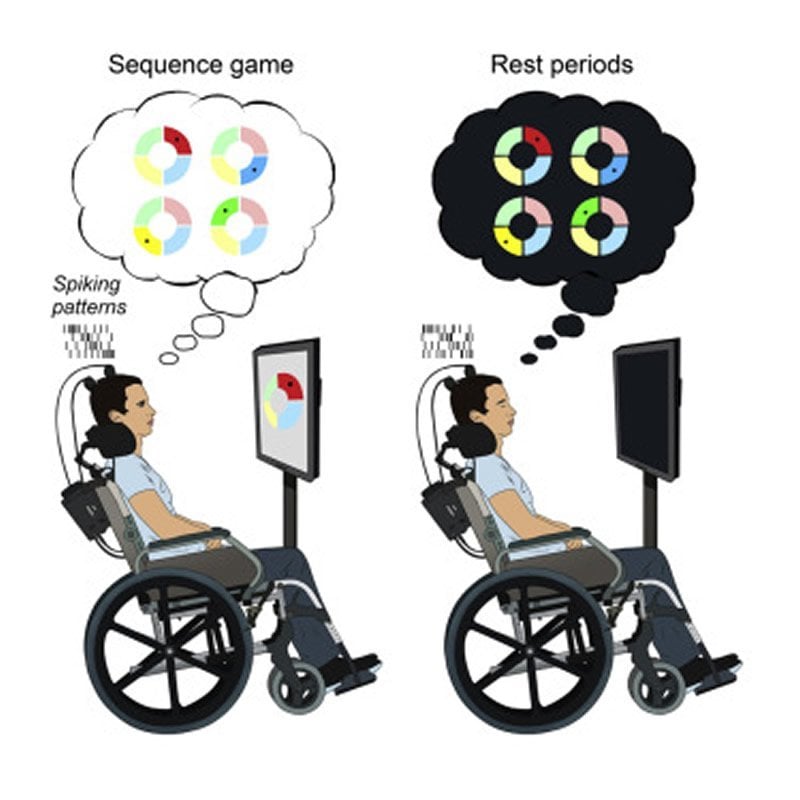

The team asked the two participants to take a nap before and after playing a sequence-copying game, which is similar to the 80s hit game Simon. The video game had four color panels that lit up in different sequences for the players to repeat. But instead of moving their arms, the participants played the game with their minds–imagining moving the cursor with their hands to different targets one by one, hitting the correct colors in the correct order as quickly as possible. While the participants rested, played the game, and then rested again, the researchers recorded the spiking activity of large groups of individual neurons in their brains through an implanted multi-electrode array.

“There aren’t a lot of scenarios in which a person would have a multi-electrode array placed in their brain, where the electrodes are tiny enough to be able to detect the firing activity of individual neurons,” says co-first author Jarosiewicz. Electrodes approved for medical indications, like those for treating Parkinson’s disease or epilepsy, are too big to track the spiking activity of single neurons. But the electrode arrays used in the BrainGate pilot clinical trials are the first to allow for such detailed neural recordings in the human brain. “That’s why this study is unprecedented,” she says.

BrainGate is an academic research consortium spanning Brown University, Massachusetts General Hospital, Case Western Reserve University, and Stanford University. Researchers at BrainGate are working to develop chronically implanted brain-computer interfaces to help people with severe motor disabilities regain communication and control by using their brain signals to move computer cursors, robotic arms, and other assistive devices.

In this study, the team observed the same neuronal firing patterns during both the gaming period and the post-game rest period. In other words, it’s as though the participants kept playing the Simon game after they were asleep, replaying the same patterns in their brain at a neuronal level. The findings provided direct evidence of learning-related replay in the human brain.

“This is the first piece of direct evidence that in humans, we also see replay during rest following learning that might help to consolidate those memories,” said Jarosiewicz. “All the replay-related memory consolidation mechanisms that we’ve studied in animals for all these decades might actually generalize to humans as well.”

The findings also open up more questions and future topics of study who want to understand the underlying mechanism by which replay enables memory consolidation. The next step is to find evidence that replay actually has a causal role in the memory consolidation process. One way to do that would be to test whether there’s a relationship between the strength of the replay and the strength of post-nap memory recall.

Although scientists don’t fully understand how learning and memory consolidation work, a cascade of animal and human studies has shown that sleep plays a vital role. Getting a good night’s sleep “before a test and before important interviews” is beneficial for good cognitive performance, said Jarosiewicz. “We have good scientific evidence that sleep is very important in these processes.”

Funding: This work was supported by the U.S. Office of Naval Research, NINDS, NIDCD, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Fyssen Foundation, and the Center for Neurorestoration and Neurotechnology from the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service. The authors would like to thank participants T9 and T10 and their families and caregivers.

About this neuroscience research article

Source:

Cell Press

Media Contacts:

Carly Britton – Cell Press

Image Source:

The image is credited to Eichenlaub and Jarosiewicz et al.

Original Research: Open access

“Replay of Learned Neural Firing Sequences during Rest in Human Motor Cortex”. by Eichenlaub and Jarosiewicz et al.

Cell Reports doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107581

Abstract

Replay of Learned Neural Firing Sequences during Rest in Human Motor Cortex

Highlights

• A brain-computer interface paradigm is used to test for memory replay in humans

• Spiking patterns that caused the learned movement sequences are replayed during rest

• Replay is stronger for learned than unlearned cursor movement sequences

• Replay occurs during both putative waking and NREM1 states

Summary

The offline “replay” of neural firing patterns underlying waking experience, previously observed in non-human animals, is thought to be a mechanism for memory consolidation. Here, we test for replay in the human brain by recording spiking activity from the motor cortex of two participants who had intracortical microelectrode arrays placed chronically as part of a brain-computer interface pilot clinical trial. Participants took a nap before and after playing a neurally controlled sequence-copying game that consists of many repetitions of one “repeated” sequence sparsely interleaved with varying “control” sequences. Both participants performed repeated sequences more accurately than control sequences, consistent with learning. We compare the firing rate patterns that caused the cursor movements when performing each sequence to firing rate patterns throughout both rest periods. Correlations with repeated sequences increase more from pre- to post-task rest than do correlations with control sequences, providing direct evidence of learning-related replay in the human brain.

Feel Free To Share This Neuroscience News.