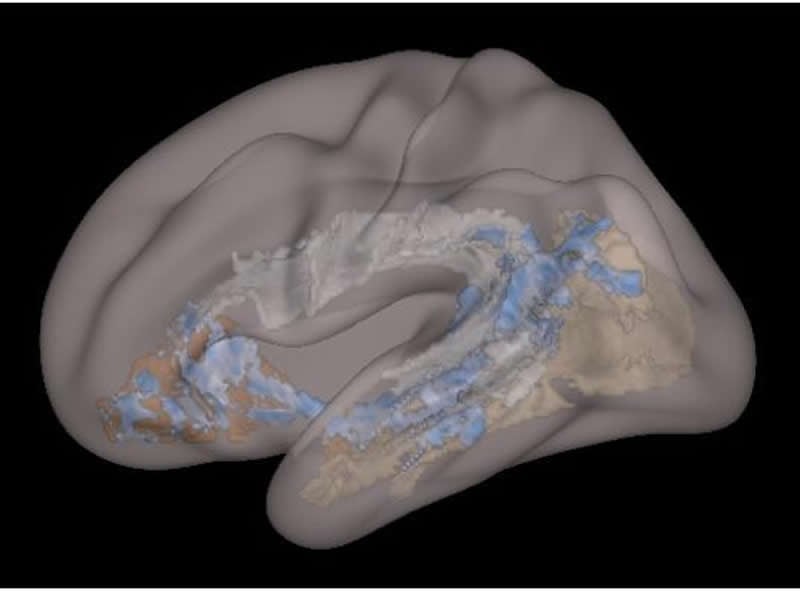

Summary: Study reveals lower microstructural integrity in white matter tracts supporting language and emergent literacy skills in prekindergarten aged children exposed to excessive screen time media.

Source: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

A new study documents structural differences in the brains of preschool-age children related to screen-based media use.

The study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, shows that children who have more screen time have lower structural integrity of white matter tracts in parts of the brain that support language and other emergent literacy skills. These skills include imagery and executive function – the process involving mental control and self-regulation. These children also have lower scores on language and literacy measures.

The Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center study assessed screen time in terms of American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendations. The AAP recommendations not only take into account time spent in front of screens but also access to screens, including portable devices; content; and who children are with and how they interact when they are looking at screens.

“This study raises questions as to whether at least some aspects of screen-based media use in early childhood may provide sub-optimal stimulation during this rapid, formative state of brain development,” says John Hutton, MD, director of the, Reading & Literacy Discovery Center at Cincinnati Children’s and lead author of the study. “While we can’t yet determine whether screen time causes these structural changes or implies long-term neurodevelopmental risks, these findings warrant further study to understand what they mean and how to set appropriate limits on technology use.”

Among the AAP recommendations:

- For children younger than 18 months, avoid use of screen media other than video-chatting. Parents of children 18 to 24 months of age who want to introduce digital media should choose high-quality programming, and watch it with their children to help them understand what they’re seeing.

- For children ages 2 to 5 years, limit screen use to 1 hour per day of high-quality programs. Parents should co-view media with children to help them understand what they are seeing and apply it to the world around them.

- Designate media-free times together, such as dinner or driving, as well as media-free locations at home, such as bedrooms.

Dr. Hutton’s study involved 47 healthy children – 27 girls and 20 boys – between 3 and 5 years old, and their parents. The children completed standard cognitive tests followed by diffusion tensor MRI, which provides estimates of white matter integrity in the brain. The researchers administered to parents a 15-item screening tool, the ScreenQ, which reflects AAP screen-based media recommendations. ScreenQ scores were then statistically associated with cognitive test scores and the MRI measures, controlling for age, gender and household income.

Among the key findings:

- Higher ScreenQ scores were significantly associated with lower expressive language, the ability to rapidly name objects (processing speed) and emergent literacy skills.

- Higher ScreenQ scores were associated with lower brain white matter integrity, which affects organization and myelination — the process of forming a myelin sheath around a nerve to allow nerve impulses to move more quickly – in tracts involving language executive function and other literacy skills.

“Screen-based media use is prevalent and increasing in home, childcare and school settings at ever younger ages,” says Dr. Hutton. “These findings highlight the need to understand effects of screen time on the brain, particularly during stages of dynamic brain development in early childhood, so that providers, policymakers and parents can set healthy limits.”

Funding: The study was funded by a Procter Scholar Award from the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation. The researchers report no financial relationships of conflicts of interest in regard to the study.

Source:

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Media Contacts:

Jim Feuer – Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Image Source:

The image is credited to Cincinnati Children’s.

Original Research: Closed access

“Associations Between Screen-Based Media Use and Brain White Matter Integrity in Preschool-Aged Children”. John S. Hutton, MS, MD et al.

JAMA Pediatrics doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3869.

Abstract

Associations Between Screen-Based Media Use and Brain White Matter Integrity in Preschool-Aged Childrent

Importance

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends limits on screen-based media use, citing its cognitive-behavioral risks. Screen use by young children is prevalent and increasing, although its implications for brain development are unknown.

Objective

To explore the associations between screen-based media use and integrity of brain white matter tracts supporting language and literacy skills in preschool-aged children.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study of healthy children aged 3 to 5 years (n = 47) was conducted from August 2017 to November 2018. Participants were recruited at a US children’s hospital and community primary care clinics.

Exposures

Children completed cognitive testing followed by diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and their parent completed a ScreenQ survey.

Main Outcomes and Measures

ScreenQ is a 15-item measure of screen-based media use reflecting the domains in the AAP recommendations: access to screens, frequency of use, content viewed, and coviewing. Higher scores reflect greater use. ScreenQ scores were applied as the independent variable in 3 multiple linear regression models, with scores in 3 standardized assessments as the dependent variable, controlling for child age and household income: Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, Second Edition (CTOPP-2; Rapid Object Naming subtest); Expressive Vocabulary Test, Second Edition (EVT-2; expressive language); and Get Ready to Read! (GRTR; emergent literacy skills). The DTI measures included fractional anisotropy (FA) and radial diffusivity (RD), which estimated microstructural organization and myelination of white matter tracts. ScreenQ was applied as a factor associated with FA and RD in whole-brain regression analyses, which were then narrowed to 3 left-sided tracts supporting language and emergent literacy abilities.

Results

Of the 69 children recruited, 47 (among whom 27 [57%] were girls, and the mean [SD] age was 54.3 [7.5] months) completed DTI. Mean (SD; range) ScreenQ score was 8.6 (4.8; 1-19) points. Mean (SD; range) CTOPP-2 score was 9.4 (3.3; 2-15) points, EVT-2 score was 113.1 (16.6; 88-144) points, and GRTR score was 19.0 (5.9; 5-25) points. ScreenQ scores were negatively correlated with EVT-2 (F2,43 = 5.14; R2 = 0.19; P < .01), CTOPP-2 (F2,35 = 6.64; R2 = 0.28; P < .01), and GRTR (F2,44 = 17.08; R2 = 0.44; P < .01) scores, controlling for child age. Higher ScreenQ scores were correlated with lower FA and higher RD in tracts involved with language, executive function, and emergent literacy abilities (P < .05, familywise error–corrected), controlling for child age and household income.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found an association between increased screen-based media use, compared with the AAP guidelines, and lower microstructural integrity of brain white matter tracts supporting language and emergent literacy skills in prekindergarten children. The findings suggest further study is needed, particularly during the rapid early stages of brain development.