Summary: At some point, we all face social rejection. Researchers say that while rejection affects us all differently, it’s how respond to the setback that determines how rejection affects us.

Source: University of New South Wales

If there’s one thing for sure, it’s that life doesn’t always go our way. A rejection, no matter the circumstance or size, can be painful, but it is something we all experience at some stage in our lives.

Dr. Kelsey Zimmermann, a researcher at the School of Psychology, UNSW Science, says while rejection affects us all differently, it’s how we respond to these setbacks that determines how they impact us.

“We all have our own experience of feeling rejected at some point, so it’s something that we can all empathize with,” Dr. Zimmermann says. “But how we process what happened to us can be critical in helping us move forward positively.”

An innate and learned fear

Fear of rejection is something that we are, at least in part, predisposed to. “Social rejection,” as it’s known in psychology, is an innate fear that we’re programmed on an evolutionary level to avoid.

We’re a very social species, so we need to show pro-social behaviors to be included in a group, and that’s been critical for our survival throughout history, says Dr. Zimmermann.

“Anything that seems intuitively aversive to us is usually there for a reason—it’s the brain trying to protect us from a perceived danger and keep us safe,” Dr. Zimmermann says. “In the same way, we naturally have an aversion to spiders and snakes—we don’t necessarily have to get bitten to know they’re something we shouldn’t touch.”

It’s why many of us fear public speaking to some degree—for some people, more than death. The idea that we could stumble on our words is frightening, but more so is the possibility that our peers will shun us.

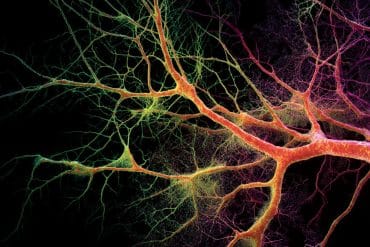

“Because of how much of our brains are devoted to social interaction, it can be a pretty profound experience to be socially rejected, so we want to avoid it. In fact, social rejection causes the same activation in brain regions associated with processing physical pain,” Dr. Zimmermann says.

But fears can also be learned through negative experiences that have hurt us in the past. In this case, prior rejections can shape how we deal with setbacks in the future and can compound over a lifetime.

“Our learned experiences can enhance that feeling of discomfort and anxiety around rejection, for example, if someone is bullied. So, if we’ve learned that people might hurt us, that’s where that fear activity in the brain comes into play,” Dr. Zimmermann says.

“If somebody experiences an unexpected romantic rejection early in life, that could cause them to develop trust issues if they don’t understand why it happened. They can carry that experience over into how they treat future romantic prospects.”

Age of rejection

Some experiences of rejection can also be more significant than others. Early life is vital for developing our social brain, and our relationships with our parents are hugely impactful.

“Experiencing rejection from a parent can profoundly impact every future interpersonal relationship,” Dr. Zimmermann says. “It’s arguably the most crucial relationship in our life that teaches us how all other connections are formed—how we can depend on people, form healthy attachments and be independent.”

Rejection is also especially formative during particular periods of our life. Social rejection during adolescence can be devastating and have long-lasting impacts into adulthood.

“No doubt many people will have some of those core memories of rejection in their teenage years. You’re extremely sensitive to multiple types of stress as the brain is strengthening and refining its connections, so rejection experiences can be particularly pronounced,” Dr. Zimmermann says.

While it’s natural to be afraid of rejection, it is always a possibility when we put ourselves out there. We’re also living in a time where the opportunity for rejection has never been more present in our daily lives.

“With our phones, we can experience rejection any time of the day or night. Anytime we post something on social media, people have the chance to reject us so overtly. Even the absence of feedback can be perceived as rejection,” Dr. Zimmermann says.

“With exponentially more opportunities for rejection, we might consider working on our relationship with rejection more.”

Navigating rejection

Though rejection is never pleasant, being too afraid of it can hold us back from pursuing what we want. The good news is that we can better deal with our fear of rejection through what psychologists call ‘cognitive reappraisal.”

“The key is to take a step back from the immediate pain and discomfort and consider reframing the situation,” Dr. Zimmermann says. “There are many instances where it’s not about you as a person. It’s about simply not being the right fit for a friendship, a relationship or a job.”

In some cases, rejection can also be a learning experience or an opportunity for self-improvement.

“If it’s something about our behavior—we’re acting in an anti-social or disrespectful way—then the rejection can be a chance for us to think about what we can work on and how we might modify that,” Dr. Zimmermann says.

Dwelling on the disappointment alone can also make the experience harder to move past. Instead, Dr. Zimmermann says it can be helpful to lean on others in our lives.

“Dealing with rejection in any part of your life is much easier if you have social support and come from a place of security—which can be a lot easier said than done,” Dr. Zimmermann says.

“If you don’t have a secure family attachment or a supportive friend group, rejection can be challenging to deal with on your own. So that’s where a therapist can help get to the root of some of your relationships with rejection.”

Finally, we can choose to see that although it hurts, rejection is an inevitable part of life. Dr. Zimmermann suggests we can start as small as we want and invite rejection into our lives to increase our tolerance.

“Take comfort in the fact that nobody lives a rejection-free life,” Dr. Zimmermann says. “If you can, put yourself out there a little more and more, and let that repeated experience take the sting out of it a bit.”

About this psychology research news

Author: Ben Knight

Source: University of New South Wales

Contact: Ben Knight – University of New South Wales

Image: The image is in the public domain