Summary: Researchers have uncovered a novel function of the hippocampus in decision making, showing that specific brain cells, known as ‘time cells,’ are stimulated by odors to facilitate rapid ‘go, no-go’ decisions.

This study demonstrates how mice learned to associate fruity odors with a reward, leading to quicker and more efficient decision making.

By tracking the activation of these cells in response to scents, the team has revealed a direct link between odor, hippocampal function, and associative learning, suggesting that these cells play a crucial role beyond memory recall, directly influencing the brain’s decision-making process.

Key Facts:

- The study identifies ‘time cells’ in the hippocampus as key players in the brain’s decision-making process, stimulated by specific odors to trigger rapid decisions.

- Mice were able to associate fruity smells with positive outcomes, showing how odor cues can enhance the learning of decision-making behaviors.

- This research sheds light on the intricate relationship between sensory perception and cognitive processes, revealing new insights into the hippocampus’s role in associative learning and decision making.

Source: University of Colorado

Researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus have discovered that odors stimulate specific brain cells that may play a role in rapid `go, no-go’ decision making.

The study was published online Tuesday in the journal Current Biology.

The scientists focused on the hippocampus, an area of the brain crucial to memory and learning. They knew that so-called `time cells’ played a major role in hippocampal function but didn’t know their role in associative learning.

“These are cells that would remind you to make a decision – do this or do that,” said the study’s senior author Diego Restrepo, PhD, a neuroscientist and professor of cell and developmental biology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

The researchers observed that when mice were given the choice of responding to a fruity smell by licking on a spout that delivered sweet water, they quickly learned to lick the fruity smell as opposed to the smell of mineral oil.

“They have to associate the odor with the outcome of what they are doing so that’s why they learn decision making,” said Ming Ma, PhD, a first author of the study and a senior instructor in cell and developmental biology at the CU School of Medicine. “When it’s a fruit odor, they lick and get a reward. When it’s mineral oil they stop licking.”

“The more they learned, the more the cells were stimulated leading to more rapid decoding of the odors and allowing the mice to quickly become proficient at choosing the fruity smell,” said Fabio Simoes de Souza, DSc, another first author of the study and an assistant research professor in cell and developmental biology at the CU School of Medicine.

The catalyst for the decision-making is the odor which travels up the nose sending neural signals to the olfactory bulb and to the hippocampus. The two organs are closely connected. The information is swiftly processed and the brain makes a decision based on the input.

“Before this we didn’t know there were decision making cells in the hippocampus,” Restrepo said. “The hippocampus is multitasking.”

The cells are not always turned on, Restrepo speculated, because otherwise the stimuli might become overwhelming.

The study expands current knowledge of what’s involved in decision-making in the brain, specifically those quick go, no-go decisions that mice and humans make all the time.

“The hippocampus turns on decision-predicting time cells which would give you a hint of what to remember,” Restrepo said. “In the past, time cells were thought to only remind you of events and time. Here we see memory encoded in the neurons and then retrieved instantly when making a decision.”

About this neuroscience research news

Author: David Kelly

Source: University of Colorado

Contact: David Kelly – University of Colorado

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Sequential activity of CA1 hippocampal cells constitutes a temporal memory map for associative learning in mice” by Diego Restrepo et al. Current Biology

Abstract

Sequential activity of CA1 hippocampal cells constitutes a temporal memory map for associative learning in mice

Sequential neural dynamics encoded by time cells play a crucial role in hippocampal function. However, the role of hippocampal sequential neural dynamics in associative learning is an open question.

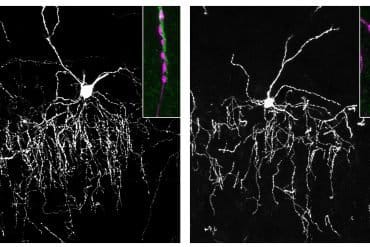

We used two-photon Ca2+ imaging of dorsal CA1 (dCA1) neurons in the stratum pyramidale (SP) in head-fixed mice performing a go-no go associative learning task to investigate how odor valence is temporally encoded in this area of the brain.

We found that SP cells responded differentially to the rewarded or unrewarded odor. The stimuli were decoded accurately from the activity of the neuronal ensemble, and accuracy increased substantially as the animal learned to differentiate the stimuli.

Decoding the stimulus from individual SP cells responding differentially revealed that decision-making took place at discrete times after stimulus presentation. Lick prediction decoded from the ensemble activity of cells in dCA1 correlated linearly with lick behavior.

Our findings indicate that sequential activity of SP cells in dCA1 constitutes a temporal memory map used for decision-making in associative learning.