Summary: Researchers have developed tiny, wireless devices capable of wrapping around individual neurons, potentially aiding in the treatment of neurological disorders like multiple sclerosis.

These devices, made from a soft polymer, roll up snugly around cell structures when exposed to light, allowing precise measurement and modulation of cellular activity. As they’re battery-free and actuated noninvasively by light, thousands of them could be deployed in the body simultaneously.

This groundbreaking approach could restore neuron function by acting as synthetic myelin for damaged axons. Future applications may include integrating circuits for neuron monitoring and treatments. The research points toward a novel direction in creating minimally invasive neural interfaces.

Key Facts:

- These cell-wearable devices are activated by light, making them battery-free.

- The devices wrap around neuronal structures, offering synthetic myelin benefits.

- Potential applications include neuron restoration and noninvasive neural modulation.

Source: MIT

Wearable devices like smartwatches and fitness trackers interact with parts of our bodies to measure and learn from internal processes, such as our heart rate or sleep stages.

Now, MIT researchers have developed wearable devices that may be able to perform similar functions for individual cells inside the body.

These battery-free, subcellular-sized devices, made of a soft polymer, are designed to gently wrap around different parts of neurons, such as axons and dendrites, without damaging the cells, upon wireless actuation with light.

By snugly wrapping neuronal processes, they could be used to measure or modulate a neuron’s electrical and metabolic activity at a subcellular level.

Because these devices are wireless and free-floating, the researchers envision that thousands of tiny devices could someday be injected and then actuated noninvasively using light.

Researchers would precisely control how the wearables gently wrap around cells, by manipulating the dose of light shined from outside the body, which would penetrate the tissue and actuate the devices.

By enfolding axons that transmit electrical impulses between neurons and to other parts of the body, these wearables could help restore some neuronal degradation that occurs in diseases like multiple sclerosis. In the long run, the devices could be integrated with other materials to create tiny circuits that could measure and modulate individual cells.

“The concept and platform technology we introduce here is like a founding stone that brings about immense possibilities for future research,” says Deblina Sarkar, the AT&T Career Development Assistant Professor in the MIT Media Lab and Center for Neurobiological Engineering, head of the Nano-Cybernetic Biotrek Lab, and the senior author of a paper on this technique.

Sarkar is joined on the paper by lead author Marta J. I. Airaghi Leccardi, a former MIT postdoc who is now a Novartis Innovation Fellow; Benoît X. E. Desbiolles, an MIT postdoc; Anna Y. Haddad ’23, who was an MIT undergraduate researcher during the work; and MIT graduate students Baju C. Joy and Chen Song.

The research appears today in Nature Communications Chemistry.

Snugly wrapping cells

Brain cells have complex shapes, which makes it exceedingly difficult to create a bioelectronic implant that can tightly conform to neurons or neuronal processes. For instance, axons are slender, tail-like structures that attach to the cell body of neurons, and their length and curvature vary widely.

At the same time, axons and other cellular components are fragile, so any device that interfaces with them must be soft enough to make good contact without harming them.

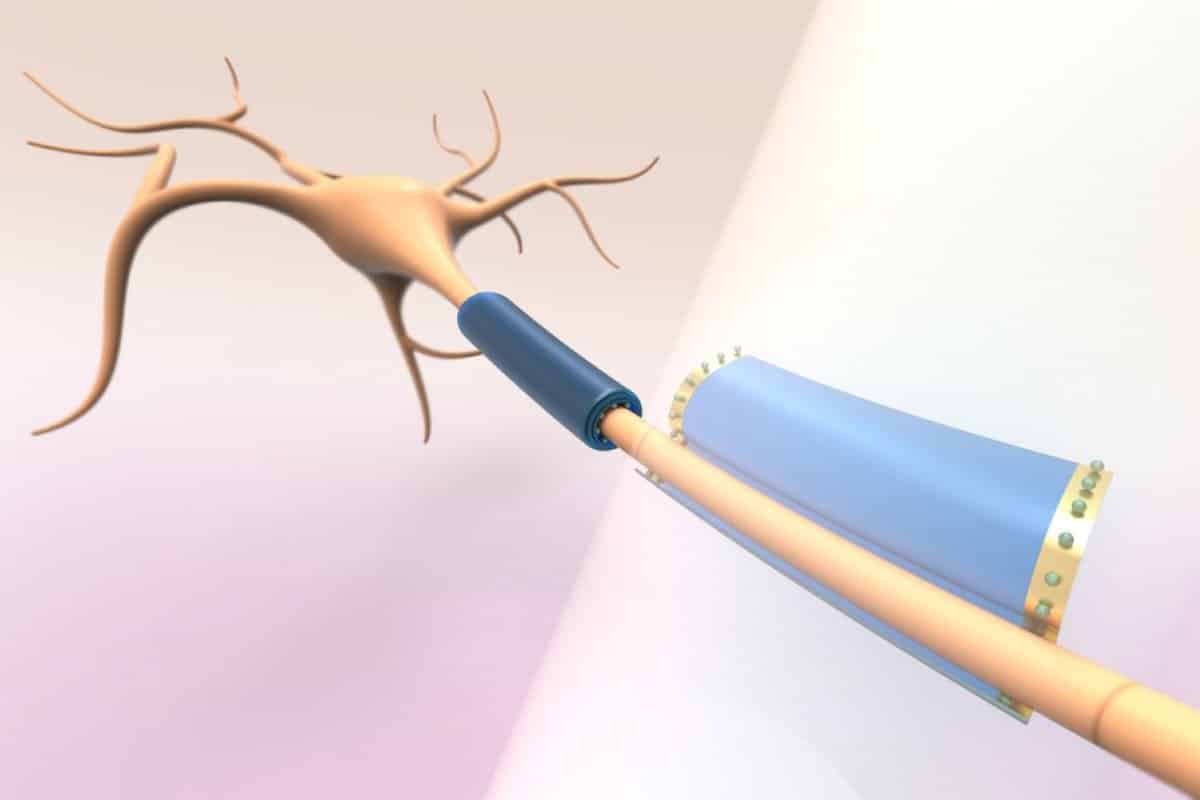

To overcome these challenges, the MIT researchers developed thin-film devices from a soft polymer called azobenzene, that don’t damage cells they enfold.

Due to a material transformation, thin sheets of azobenzene will roll when exposed to light, enabling them to wrap around cells. Researchers can precisely control the direction and diameter of the rolling by varying the intensity and polarization of the light, as well as the shape of the devices.

The thin films can form tiny microtubes with diameters that are less than a micrometer. This enables them to gently, but snugly, wrap around highly curved axons and dendrites.

“It is possible to very finely control the diameter of the rolling. You can stop if when you reach a particular dimension you want by tuning the light energy accordingly,” Sarkar explains.

The researchers experimented with several fabrication techniques to find a process that was scalable and wouldn’t require the use of a semiconductor clean room.

Making microscopic wearables

They begin by depositing a drop of azobenzene onto a sacrificial layer composed of a water-soluble material. Then the researchers press a stamp onto the drop of polymer to mold thousands of tiny devices on top of the sacrificial layer. The stamping technique enables them to create complex structures, from rectangles to flower shapes.

A baking step ensures all solvents are evaporated and then they use etching to scrape away any material that remains between individual devices. Finally, they dissolve the sacrificial layer in water, leaving thousands of microscopic devices freely floating in the liquid.

Once they have a solution with free-floating devices, they wirelessly actuated the devices with light to induce the devices to roll. They found that free-floating structures can maintain their shapes for days after illumination stops.

The researchers conducted a series of experiments to ensure the entire method is biocompatible.

After perfecting the use of light to control rolling, they tested the devices on rat neurons and found they could tightly wrap around even highly curved axons and dendrites without causing damage.

“To have intimate interfaces with these cells, the devices must be soft and able to conform to these complex structures. That is the challenge we solved in this work. We were the first to show that azobenzene could even wrap around living cells,” she says.

Among the biggest challenges they faced was developing a scalable fabrication process that could be performed outside a clean room. They also iterated on the ideal thickness for the devices, since making them too thick causes cracking when they roll.

Because azobenzene is an insulator, one direct application is using the devices as synthetic myelin for axons that have been damaged. Myelin is an insulating layer that wraps axons and allows electrical impulses to travel efficiently between neurons.

In non-myelinating diseases like multiple sclerosis, neurons lose some insulating myelin sheets. There is no biological way of regenerating them. By acting as synthetic myelin, the wearables might help restore neuronal function in MS patients.

The researchers also demonstrated how the devices can be combined with optoelectrical materials that can stimulate cells.

Moreover, atomically thin materials can be patterned on top of the devices, which can still roll to form microtubes without breaking. This opens up opportunities for integrating sensors and circuits in the devices.

In addition, because they make such a tight connection with cells, one could use very little energy to stimulate subcellular regions. This could enable a researcher or clinician to modulate electrical activity of neurons for treating brain diseases.

“It is exciting to demonstrate this symbiosis of an artificial device with a cell at an unprecedented resolution. We have shown that this technology is possible,” Sarkar says.

In addition to exploring these applications, the researchers want to try functionalizing the device surfaces with molecules that would enable them to target specific cell types or subcellular regions.

“This work is an exciting step toward new symbiotic neural interfaces acting at the level of the individual axons and synapses.

“When integrated with nanoscale 1- and 2D conductive nanomaterials, these light-responsive azobenzene sheets could become a versatile platform to sense and deliver different types of signals (i.e., electrical, optical, thermal, etc.) to neurons and other types of cells in a minimally or noninvasive manner.

“Although preliminary, the cytocompatibility data reported in this work is also very promising for future use in vivo,” says Flavia Vitale, associate professor of neurology, bioengineering, and physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Pennsylvania, who was not involved with this work.

Funding: The research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the U.S. National Institutes of Health Brain Initiative.

About this neurotech research news

Author: Adam Zewe

Source: MIT

Contact: Adam Zewe – MIT

Image: The image is credited to Pablo Penso and Marta Airaghi

Original Research: Open access.

“Light-induced rolling of azobenzene polymer thin films for wrapping subcellular neuronal structures” by Deblina Sarkar et al. Nature Communications Chemistry

Abstract

Light-induced rolling of azobenzene polymer thin films for wrapping subcellular neuronal structures

Neurons are essential cells composing our nervous system and orchestrating our body, thoughts, and emotions. Recently, research efforts have been focused on studying not only their collective structure and functions but also the single-cell properties as an individual complex system.

Nanoscale technology has the potential to unravel mysteries in neuroscience and provide support to the neuron by measuring and influencing several aspects of the cell.

As wearable devices interact with different parts of our body, we could envision a thousand times smaller interface to conform on and around subcellular regions of the neurons for unprecedented contact, probing, and control.

However, a major challenge is to develop an interface that can morph to the extreme curvatures of subcellular structures.

Here, we address this challenge with the development of a platform that conforms even to small neuronal processes.

To achieve this, we produced a wireless platform made of an azobenzene polymer that undergoes on-demand light-induced folding with sub-micrometer radius of curvature.

We show that these platforms can be fabricated with an adjustable form factor, micro-injected onto neuronal cultures, and can delicately wrap various morphologies of neuronal processes in vitro, toward obtaining seamless biointerfaces with an increased coupling with the cell membrane. Our in vitro testings did not show any adverse effects of the platforms in contact with the neurons.

Additionally, for future functionality, nanoparticles or optoelectronic materials could be blended with the azobenzene polymer, and 2D materials on the platform surface could be safely folded to the high curvatures without mechanical failure, as per our calculations.

Ultimately, this technology could lay the foundation for future integration of wirelessly actuated materials within or on its platform for neuromodulation, recording, and neuroprotection at the subcellular level.