Summary: A new Current Biology study reveals there appears to be a strong genetic component to how people visually explore their environments.

Source: Indiana University.

A new study co-led by Indiana University that tracked the eye movement of twins finds that genetics plays a strong role in how people attend to their environment.

Conducted in collaboration with researchers from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, the study offers a new angle on the emergence of differences between individuals and the integration of genetic and environmental factors in social, emotional and cognitive development. This is significant because visual exploration is also one of the first ways infants interact with the environment, before they can reach or crawl.

“The majority of work on eye movement has asked ‘What are the common features that drive our attention?'” said Daniel P. Kennedy, an assistant professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. “This study is different. We wanted to understand differences among individuals and whether they are influenced by genetics.”

Kennedy and co-author Brian M. D’Onofrio, a professor in the department, study neurodevelopmental problems from different perspectives. This work brings together their contrasting experimental methods: Kennedy’s use of eye tracking for individual behavioral assessment and D’Onofrio’s use of genetically informed designs, which draw on data from large population samples to trace the genetic and environmental contributions to various traits. As such, it is one of the largest-ever eye-tracking studies.

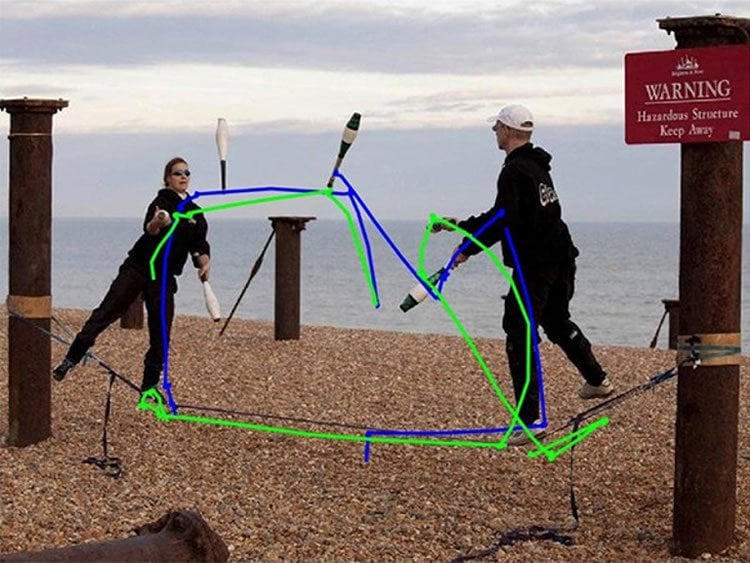

In this particular experiment, the researchers compared the eye movements of 466 children — 233 pairs of twins (119 identical and 114 fraternal) — between ages 9 and 14 as each child looked at 80 snapshots of scenes people might encounter in daily life, half of which included people. Using an eye tracker, the researchers then measured the sequence of eye movements in both space and time as each child looked at the scene. They also examined general “tendencies of exploration”; for example, if a child looked at only one or two features of a scene or at many different ones.

Published today in the journal Current Biology, the study found a strong similarity in gaze patterns within sets of identical twins, who tended to look at the same features of a scene in the same order. It found a weaker but still pronounced similarity between fraternal twins.

This suggests a strong genetic component to the way individuals visually explore their environments: Insofar as both identical and fraternal twins each share a common environment with their twin, the researchers can infer that the more robust similarity in the eye movements of identical twins is likely due to their shared genetic makeup. The researchers also found that they could reliably identify a twin with their sibling from among a pool of unrelated individuals based on their shared gaze patterns — a novel method they termed “gaze fingerprinting.”

“People recognize that gaze is important,” Kennedy said. “Our eyes are moving constantly, roughly three times per second. We are always seeking out information and actively engaged with our environment, and ultimately where you look affects your development.”

After early childhood, the study suggests that genes influence at the micro-level — through the immediate, moment-to-moment selection of visual information — the environments individuals create for themselves.

“This is not a subtle statistical finding,” Kennedy said. “How people look at images is diagnostic of their genetics. Eye movements allow individuals to obtain specific information from a space that is vast and largely unconstrained. It’s through this selection process that we end up shaping our visual experiences.

“Less known are the biological underpinnings of this process,” he added. “From this work, we now know that our biology affects how we seek out visual information from complex scenes. It gives us a new instance of how biology and environment are integrated in our development.”

“This finding is quite novel in the field,” D’Onofrio said. “It is going to surprise people in a number of fields, who do not typically think about the role of genetic factors in regulating such processes as where people look.”

Additional researchers on the paper are Patrick D. Quinn, a postdoctoral student in the IU Bloomington Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, and Sven Bölte, Paul Lichtenstein and Terje Falck-Ytter of the Karolinska Institute.

Funding: This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by the Swedish Research Council, Karolinska Institute and IU.

Source: Indiana University

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to the researchers.

Original Research: Abstract for “Genetic Influence on Eye Movements to Complex Scenes at Short Timescales” by Daniel P. Kennedy, Brian M. D’Onofrio, Patrick D. Quinn, Sven Bölte, Paul Lichtenstein, and Terje Falck-Ytter in Current Biology. Published online November 9 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.007

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Indiana University “Genetics Affect Where Children Look.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 11 November 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/genetics-eye-tracking-kids-7924/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Indiana University (2017, November 11). Genetics Affect Where Children Look. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved November 11, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/genetics-eye-tracking-kids-7924/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Indiana University “Genetics Affect Where Children Look.” https://neurosciencenews.com/genetics-eye-tracking-kids-7924/ (accessed November 11, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Genetic Influence on Eye Movements to Complex Scenes at Short Timescales

Highlights

•We recorded eye movements in a large sample of identical and fraternal twins

•We find eye movements to complex social and nonsocial scenes are heritable

•The influence of genes manifests even in the precise temporal order of fixations

•This demonstrates that genes can shape the active selection of visual experiences

Summary

Where one looks within their environment constrains one’s visual experiences, directly affects cognitive, emotional, and social processing, influences learning opportunities, and ultimately shapes one’s developmental path. While there is a high degree of similarity across individuals with regard to which features of a scene are fixated, large individual differences are also present, especially in disorders of development, and clarifying the origins of these differences is essential to understand the processes by which individuals develop within the complex environments in which they exist and interact. Toward this end, a recent paper found that “social visual engagement”—namely, gaze to eyes and mouths of faces—is strongly influenced by genetic factors. However, whether genetic factors influence gaze to complex visual scenes more broadly, impacting how both social and non-social scene content are fixated, as well as general visual exploration strategies, has yet to be determined. Using a behavioral genetic approach and eye tracking data from a large sample of 11-year-old human twins (233 same-sex twin pairs; 51% monozygotic, 49% dizygotic), we demonstrate that genetic factors do indeed contribute strongly to eye movement patterns, influencing both one’s general tendency for visual exploration of scene content, as well as the precise moment-to-moment spatiotemporal pattern of fixations during viewing of complex social and non-social scenes alike. This study adds to a now growing set of results that together illustrate how genetics may broadly influence the process by which individuals actively shape and create their own visual experiences.

“Genetic Influence on Eye Movements to Complex Scenes at Short Timescales” by Daniel P. Kennedy, Brian M. D’Onofrio, Patrick D. Quinn, Sven Bölte, Paul Lichtenstein, and Terje Falck-Ytter in Current Biology. Published online November 9 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.007