Summary: By looking at how the brain responds to video clips, researchers are able to determine who your friends may be, a new study reveals.

Source: Dartmouth College.

You may perceive the world the way your friends do, according to a Dartmouth study finding that friends have similar neural responses to real-world stimuli and these similarities can be used to predict who your friends are.

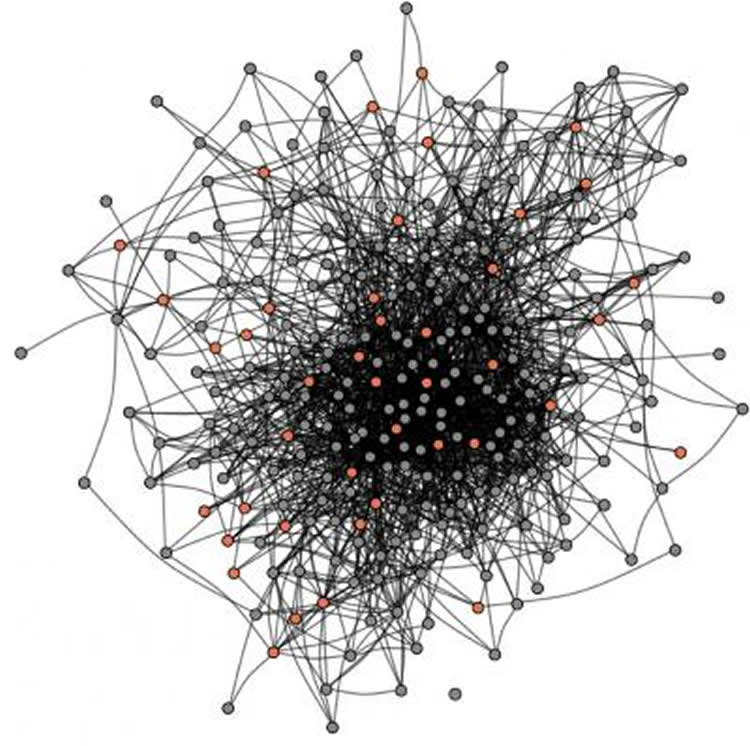

The researchers found that you can predict who people are friends with just by looking at how their brains respond to video clips. Friends had the most similar neural activity patterns, followed by friends-of-friends who, in turn, had more similar neural activity than people three degrees removed (friends-of-friends-of-friends).

Published in Nature Communications, the study is the first of its kind to examine the connections between the neural activity of people within a real-world social network, as they responded to real-world stimuli, which in this case was watching the same set of videos.

“Neural responses to dynamic, naturalistic stimuli, like videos, can give us a window into people’s unconstrained, spontaneous thought processes as they unfold. Our results suggest that friends process the world around them in exceptionally similar ways,” says lead author Carolyn Parkinson, who was a postdoctoral fellow in psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth at the time of the study and is currently an assistant professor of psychology and director of the Computational Social Neuroscience Lab at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The study analyzed the friendships or social ties within a cohort of nearly 280 graduate students. The researchers estimated the social distance between pairs of individuals based on mutually reported social ties. Forty-two of the students were asked to watch a range of videos while their neural activity was recorded in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner. The videos spanned a range of topics and genres, including politics, science, comedy and music videos, for which a range of responses was expected. Each participant watched the same videos in the same order, with the same instructions. The researchers then compared the neural responses pairwise across the set of students to determine if pairs of students who were friends had more similar brain activity than pairs further removed from each other in their social network.

The findings revealed that neural response similarity was strongest among friends, and this pattern appeared to manifest across brain regions involved in emotional responding, directing one’s attention and high-level reasoning. Even when the researchers controlled for variables, including left-handed- or right-handedness, age, gender, ethnicity, and nationality, the similarity in neural activity among friends was still evident. The team also found that fMRI response similarities could be used to predict not only if a pair were friends but also the social distance between the two.

“We are a social species and live our lives connected to everybody else. If we want to understand how the human brain works, then we need to understand how brains work in combination– how minds shape each other,” explains senior author Thalia Wheatley, an associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth, and principal investigator of the Dartmouth Social Systems Laboratory.

For the study, the researchers were building on their earlier work, which found that as soon as you see someone you know, your brain immediately tells you how important or influential they are and the position they hold in your social network.

The research team plans to explore if we naturally gravitate toward people who see the world the same way we do, if we become more similar once we share experiences or if both dynamics reinforce each other.

Source: Amy D. Olson – Dartmouth College

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Carolyn Parkinson.

Original Research: Open access research in Nature Communications.

doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02722-7

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Dartmouth College “Your Brain Reveals Who Your Friends Are.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 30 January 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/friends-brain-8402/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Dartmouth College (2018, January 30). Your Brain Reveals Who Your Friends Are. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved January 30, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/friends-brain-8402/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Dartmouth College “Your Brain Reveals Who Your Friends Are.” https://neurosciencenews.com/friends-brain-8402/ (accessed January 30, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Similar neural responses predict friendship

Human social networks are overwhelmingly homophilous: individuals tend to befriend others who are similar to them in terms of a range of physical attributes (e.g., age, gender). Do similarities among friends reflect deeper similarities in how we perceive, interpret, and respond to the world? To test whether friendship, and more generally, social network proximity, is associated with increased similarity of real-time mental responding, we used functional magnetic resonance imaging to scan subjects’ brains during free viewing of naturalistic movies. Here we show evidence for neural homophily: neural responses when viewing audiovisual movies are exceptionally similar among friends, and that similarity decreases with increasing distance in a real-world social network. These results suggest that we are exceptionally similar to our friends in how we perceive and respond to the world around us, which has implications for interpersonal influence and attraction.