Summary: Studying red junglefowl chicks, researchers conclude impulsivity is linked to both gene expression and early life experiences.

Source: Linköping University

Differences in impulsivity between individuals are linked to both experience and gene expression, according to a study on the ancestor of domestic chickens, the red junglefowl.

The study from Linköping University, Sweden, has been published in the journal Animal Behaviour.

More impulsive individuals are more likely to respond rapidly to situations without planning or considering the consequences. In many species, including humans, impulsivity differs between individuals, but we do not yet understand why this is, as research into what lies behind these differences is limited.

“Variation in impulsivity is especially puzzling, because individuals with high impulsivity can suffer negative consequences, such as taking risks without considering the outcome. We expect natural selection over time to favour behaviour that benefits the individual, so why do we regularly observe individuals who are considerably more impulsive than others?” asks Hanne Løvlie, associate professor in the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Biology at Linköping University, who led the study.

The LiU researchers looked in more detail at how impulsivity could be influenced by underlying factors. They studied the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus), the ancestor of our domestic chickens and a frequently used species for studies on behavioural differences and cognition, measuring animal “intelligence”.

To investigate whether junglefowl chicks differed in impulsivity, the researchers used an already established test in which a reward (a mealworm) is placed inside a transparent tube.

The impulsive response is to try to reach the reward directly through the solid, transparent side of the tube, even though this is not possible. To get the mealworm, a chick must instead curb its impulsivity and remember what it has previously learnt – that it can reach the reward from the open end of the tube.

The researchers counted how many times each chick pecked at the transparent tube trying to get the reward, which is a measure of how impulsive they were. By repeating the experiment several times, the researchers also measured how well each chick learnt to reduce its impulsivity.

The scientists wanted to see how early experiences could influence impulsivity. Before testing how impulsive chicks were, they assigned each chick at random to one of three treatments.

In one treatment, chicks received training which aimed to improve their cognitive abilities, resulting in ‘cognitively enriched’ chicks.

Chicks in the second treatment were permitted to interact with the cognitive testing equipment, but were not trained themselves, and were thus ‘environmentally enriched’ (but not cognitively enriched). Chicks in the third treatment did not receive any enrichment while growing up.

The results showed that these differences in early experience did indeed affect impulsivity in the junglefowl chicks, but not in the manner that was expected.

“Intriguingly, cognitively enriched chicks, who had been trained to pass other cognitive tests, were more impulsive than the other chicks. This goes against our initial expectations but is compatible with our finding that environmentally enriched chicks were slower to learn to reduce impulsivity. Thus, all chicks that received enrichment were less able to curb their impulsivity.

“Our results support discoveries from earlier studies that suggest that enrichment can increase impulsivity, and highlight the potential role of cognitive enrichment”, says Laura Garnham, PhD student at LiU and one of the researchers behind the study.

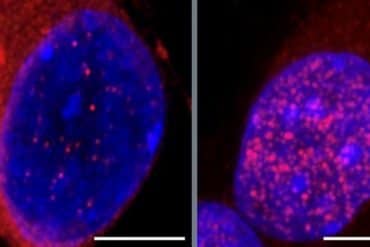

Variation between individuals was also influenced by brain gene expression. The scientists investigated the levels of expression of several genes that are involved in two important brain signalling systems, the serotonin system and the dopamine system, which in other species have been linked to impulsive behaviour.

“We found that impulsivity correlated with the expression of one gene linked to the signalling molecule serotonin, and two genes linked to the signalling molecule dopamine.

“This shows us that not only differences in experience, but also genetic factors can contribute to differences in impulsivity between individuals”, says Sara Ryding, who worked in the study while on an exchange visit from the University of Manchester. Sara is now a PhD student at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia.

Funding: The research has received financial support from the FORMAS research council.

About this genetics and psychology research news

Author: Hanne Løvlie

Source: Linköping University

Contact: Hanne Løvlie – Linköping University

Image: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Open access.

“Impulsivity is affected by cognitive enrichment and links to brain gene expression in red junglefowl chicks” by Hanne Løvlie et al. Animal Behavior

Abstract

Impulsivity is affected by cognitive enrichment and links to brain gene expression in red junglefowl chicks

Despite reported findings, explanations for within-species variation in behavioural performance on cognitive tests are still understudied. Cognitive processes are influenced by environmental and genetic differences, where cognitive stimulation and monoaminergic systems are predicted to be important.

To explore explanations for individual variation in impulsivity (a behaviour that is negatively correlated with inhibitory control), we experimentally altered the environment of red junglefowl, Gallus gallus, by exposing chicks from newly hatched to 9 weeks old to either (1) both environmental and cognitive enrichment, (2) environmental enrichment without additional cognitive enrichment or (3) neither environmental nor cognitive enrichment. Subsequently, we measured variation in impulsivity and brain gene expression of genes from the dopaminergic system (DRD1 and DRD2) and serotonergic system (5HT2A, 5HT1B, 5HT2B, 5HT2C and TPH). We focused on two aspects of impulsivity, impulsive action and persistence, and their reduction over time.

Cognitively enriched chicks tended to have higher initial impulsive action and had higher initial persistence, and our environmentally enriched chicks had slower reduction of impulsive action over time. DRD2 (a dopamine receptor gene) had lower expression in environmentally enriched chicks. Variation in impulsive action tended to correlate with expression of TPH (a gene involved in serotonin synthesis), whereas persistence correlated with both TPH and the dopamine receptor gene DRD1, and tended to correlate with the dopaminergic gene DRD2, regardless of rearing treatment.

These results indicate that both environment and links to neurobiology could explain initial individual variation in, and reduction of, impulsivity. Further, distinct neurobiological pathways appear to govern impulsive action versus persistence, supporting the suggestion that impulsivity is a heterogenic behaviour.