Summary: Neuroimaging study sheds light on what drove the evolutionary development of human creativity.

Source: Drexel University

Creativity is one of humanity’s most distinctive abilities and enduring mysteries. Innovative ideas and solutions have enabled our species to survive existential threats and thrive. Yet, creativity cannot be necessary for survival because many species that do not possess it have managed to flourish far longer than humans. So what drove the evolutionary development of creativity? A new neuroimaging study led by Yongtaek Oh, a Drexel University doctoral candidate, and John Kounios, PhD, a professor in Drexel’s College of Arts and Sciences and director of its Creativity Research Lab, points to an answer.

The study, recently published in NeuroImage, discovered that, in some people, creative insights, colloquially known as “aha moments,” trigger a burst of activity in the brain’s reward system — the same system which responds to delicious foods, addictive substances, orgasms and other basic pleasures.

Because reward-system activity motivates the behaviors that produce it, individuals who experience insight-related neural rewards are likely to engage in further creativity-related activities, potentially to the exclusion of other activities — a notion that many puzzle aficionados, mystery-novel devotees, starving artists and underpaid researchers may find familiar, according to Kounios.

“The fact that evolution has linked the generation of new ideas and perspectives to the human brain’s reward system may explain the proliferation of creativity and the advancement of science and culture,” said Kounios.

The study focused on the phenomenon of aha moments, or insights, as prototypical instances of creativity. Insights are sudden experiences of nonobvious perspectives, ideas or solutions that can lead to inventions and other breakthroughs. Many people report that insights are accompanied by a mind-expanding rush of pleasure.

The team recorded people’s high-density electroencephalograms (EEGs) while they solved anagram puzzles, which required them to unscramble a set of letters to find a hidden word. Such puzzles serve as small-scale models of more complex forms of problem-solving and idea generation. They noted which solutions were achieved as insights that suddenly popped into awareness, in contrast to solutions that were generated by methodically rearranging the letters to look for the right order.

Importantly, the test subjects also filled out a questionnaire that measured their “reward sensitivity,” a basic personality trait that reflects the degree to which an individual is generally motivated to gain rewards rather than avoid losing them.

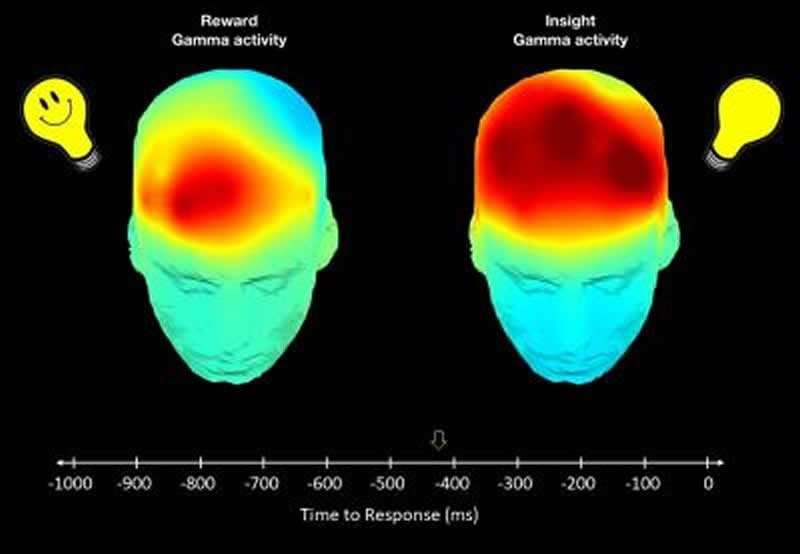

The test subjects showed a burst of high-frequency “gamma-band” brainwaves associated with aha-moment solutions. However, only highly reward-sensitive people showed an additional burst of high-frequency gamma waves about a tenth of a second later. This second burst originated in orbitofrontal cortex, a part of brain’s reward system.

The study shows that some people experience creative insights as intrinsically rewarding. Because this reward-related burst of neural activity occurred so quickly after the initial insight, only a tenth of a second, it did not result from a conscious appraisal of the solution. Rather, this fast reward response was triggered by, or integrated with, the insight itself.

Low-reward-sensitivity test subjects did experience nearly as many insights as the high-reward-sensitivity ones, but their insights did not trigger a significant neural reward response. Thus, neural reward is not a necessary accompaniment to insight, though it occurs in many people.

This study suggests that measurements of general reward sensitivity may help to predict who will practice, develop and expand their creative abilities over time.

Funding: The study, “An Insight-Related Neural Reward Signal” was funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation and was published in the journal NeuroImage. Co-authors include Christine Chesebrough, doctoral student; Brian Erickson, post-doctoral researcher; and Fengqing (Zoe) Zhang, PhD, of Drexel University.

About this neuroscience research article

Source:

Drexel University

Media Contacts:

Annie Korp – Drexel University

Image Source:

The image is credited to Drexel University.

Original Research: Open access

“An insight-related neural reward signal”. Yongtaek Oh, Christine Chesebrough, Brian Erickson, Fengqing Zhang, John Kounios.

Neurolmage doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116757.

Abstract

An insight-related neural reward signal

Moments of insight, a phenomenon of creative cognition in which an idea suddenly emerges into awareness as an “Aha!” are often reported to be affectively positive experiences. We tested the hypothesis that problem-solving by insight is accompanied by neural reward processing. We recorded high-density EEGs while participants solved a series of anagrams. For each solution, they reported whether the answer had occurred to them as a sudden insight or whether they had derived it deliberately and incrementally (i.e., “analytically’). Afterwards, they filled out a questionnaire that measures general dispositional reward sensitivity. We computed the time-frequency representations of the EEGs for trials with insight (I) solutions and trials with analytic (A) solutions and subtracted them to obtain an I-A time-frequency representation for each electrode. Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) analyses tested for significant I-A and reward-sensitivity effects. SPM revealed the time, frequency, and scalp locations of several I > A effects. No A > I effect was observed. The primary neural correlate of insight was a burst of (I > A) gamma-band oscillatory activity over prefrontal cortex approximately 500 ms before participants pressed a button to indicate that they had solved the problem. We correlated the I-A time-frequency representation with reward sensitivity to discover insight-related effects that were modulated by reward sensitivity. This revealed a separate anterior prefrontal burst of gamma-band activity, approximately 100 ms after the primary I-A insight effect, which we interpreted to be an insight-related reward signal. This interpretation was supported by source reconstruction showing that this signal was generated in part by orbitofrontal cortex, a region associated with reward learning and hedonically pleasurable experiences such as food, positive social experiences, addictive drugs, and orgasm. These findings support the notion that for many people insight is rewarding. Additionally, these results may explain why many people choose to engage in insight-generating recreational and vocational activities such as solving puzzles, reading murder mysteries, creating inventions, or doing research. This insight-related reward signal may be a manifestation of an evolutionarily adaptive mechanism for the reinforcement of exploration, problem solving, and creative cognition.

Feel Free To Share This Neuroscience News.