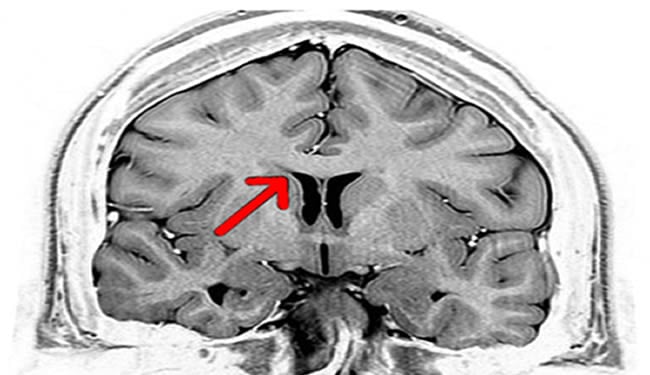

Corpus collosum connections begin to deteriorate in old aged brains. The loss of corpus collosum connections leads to more crosstalk between the brain hemispheres than is seen in younger brains with less damaged corpus collosum connections. This research shows that the loss of connections in the corpus collosum could be partly responsible for slower response times seen in older animals and humans due to too much crosstalk and confusion between the brain hemispheres.

Brain connections break down as we age

It’s unavoidable: breakdowns in brain connections slow down our physical response times as we age, a new study suggests.

This slower reactivity is associated with an age-related breakdown in the corpus callosum, a part of the brain that acts as a dam during one-sided motor activities to prevent unwanted connectivity, or cross-talk, between the two halves of the brain, said Rachael Seidler, associate professor in the University of Michigan School of Kinesiology and Department of Psychology, and lead study author.

At other times the corpus callosum acts at a bridge and cross-talk is helpful, such as in certain cognitive functions or two-sided motor skills.

The U-M study is the first known to show that this cross-talk happens even while older adults are at rest, said Seidler, who also has appointments in the Institute of Gerontology and the Neuroscience Graduate Program. This resting cross-talk suggests that it is not helpful or compensatory for the two halves of the brain to communicate during one-sided motor movements because the opposite side of the brain controls the part of the body that is moving. So, when both sides of the brain talk simultaneously while one side of the body tries to move, confusion and slower responses result, Seidler said.

Previous studies have shown that cross-talk in the brain during certain motor tasks increases with age but it wasn’t clear if that cross-talk helped or hindered brain function, said Seidler.

“Cross-talk is not a function of task difficulty, because we see these changes in the brain when people are not moving,” Seidler said.

In some diseases where the corpus callosum is very deteriorated, such as in people with multiple sclerosis, you can see “mirror movements” during one sided-motor tasks, where both sides move in concert because there is so much communication between the two hemispheres of the brain, Seidler said. These mirror movements also happen normally in very young children before the corpus callosum is fully developed.

In the study, researchers gave joysticks to adults between the ages of 65 and 75 and measured and compared their response times against a group approximately 20-25 years old.

Researchers then used a functional MRI to image the blood-oxygen levels in different parts of the brain, a measurement of brain activity.

“The more they recruited the other side of the brain, the slower they responded,” Seidler said.

However there is hope, and just because we inevitably age doesn’t mean it’s our fate to react more slowly. Seidler’s group is working on developing and piloting motor training studies that might rebuild or maintain the corpus callosum to limit overflow between hemispheres, she said.

A previous study done by another group showed that doing aerobic training for three months helped to rebuild the corpus callosum, she said, which suggests that physical activity can help to counteract the effects of the age-related degeneration.

Seidler’s group also has a study in review that uses the same brain imaging techniques to examine disease related brain changes in Parkinson’s patients.

About this neuroscience study:

The study appeared in the journal Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience.

For more on Seidler: http://www.kines.umich.edu/faculty/full-time/seidler.html

For more on Kinesiology: http://www.kines.umich.edu/

The University of Michigan School of Kinesiology continues to be a leader in the areas of prevention and rehabilitation, the business of sport, understanding lifelong health and mobility, and achieving health across the lifespan through physical activity. The School of Kinesiology is home to the Athletic Training, Movement Science, Physical Education, and Sport Management academic programs—bringing together leaders in physiology, biomechanics, public health, urban planning, economics, marketing, public policy, and education and behavioral science.

Contact: Laura Bailey

Source: University of Michigan