Summary: Male worms can activate two conflicting memories—mating and starvation—when encountering the same odor, but only one influences their behavior. A study conditioned worms to associate the smell with both positive (mating) and negative (starvation) experiences, revealing that mating associations overrode avoidance behavior.

This flexible memory processing highlights how the brain prioritizes rewards over punishment under certain conditions. The findings provide insights into memory-driven behavior and offer a model for studying maladaptive processes in disorders like PTSD.

Key Facts:

- Male worms can activate conflicting memories, but only one dictates behavior.

- Positive (mating) memories can override negative (starvation) associations.

- Insights into memory processing could inform PTSD and other neurobehavioral research.

Source: UCL

Two conflicting memories can both be activated in a worm’s brain, even if only one memory actively drives the animal’s behaviour, finds a new study by UCL researchers.

In the paper published in Current Biology, the researchers showed how an animal’s sex drive can at times outweigh the need to eat when determining behaviour, as they investigated what happens when a worm smells an odour that has been linked to both good experiences (mating) and bad experiences (starvation).

The scientists were seeking to understand how an animal’s brain decides if something it encounters is good or bad, and how this determines the animal’s response.

They found that by conditioning male worms to have both positive and negative associations with an odour, both memories will be activated when the worm smells the odour, but only one will impact the animal’s behaviour.

The researchers say their findings can be further investigated to gain insight into health conditions where this process goes wrong, such as in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), where memories that should remain latent (dormant) are still problematically influencing behaviours and emotions.

Lead author Dr Arantza Barrios (UCL Cell & Developmental Biology) said: “For our study, we were looking into the brain of the male worm, in order to understand the cellular or molecular mechanisms that determine if a particular memory impacts behaviour. An important part of how we learn is that our brains are able to adapt to new information and override previous associations.”

Co-first author Dr Susana Colinas Fischer (UCL Cell & Developmental Biology) added: “By understanding what a very small worm is thinking, we are able to learn more about the processes underlying our own more complex thinking patterns.”

The study was undertaken with male C. elegans roundworms, a species of worm 1mm in length that is very commonly used as a model organism in scientific research. The worms were presented with an odour that is innately attractive to them, which the researchers say is akin to a person smelling a delicious dinner.

In a series of experiments, the researchers modified the worms’ preference for the odour and monitored their behaviour and brain activity.

The worms’ instinct to approach the odour was overridden with aversive conditioning, in which the worms experienced the odour together with a punishment of starvation.

The researchers then sought to override this learned avoidance with further conditioning, whereby the odour was presented alongside a female mate and some sexual experience, so that the male worms developed a new positive association with the odour.

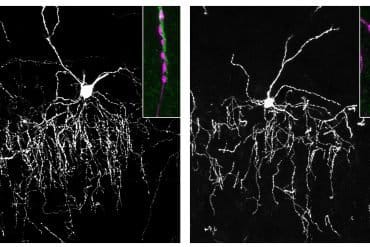

The analysis identified a circuit of brain cells that represents both positive and negative associations with things the animal has encountered previously, centred on a particular neuropeptide (a chemical messenger in the brain) that stores the memories of both the starvation and mating associations with the odour.

The researchers found that in worms that had been conditioned to associate the odour with starvation and mating, both memories were activated in the brain. But only one of them – the mating association – still caused the worm to approach the odour.

The researchers say this indicates that the prospect of a mating reward overrode the prospect of a starvation punishment, even though both memories remained intact – while the worm no longer avoided the odour, the negative memory of starvation was still represented in the brain activity.

Co-first author Dr Laura Molina-García (UCL Cell & Developmental Biology) said: “We found that even in an animal with a very small brain like that of a roundworm, two conflicting memories can both be activated at the same time, with one memory impacting behaviour and one memory remaining latent.

“The way an animal’s brain can flexibly represent something that is partly good and partly bad helps it to learn and adapt to new information.

“By understanding how some memories can override other conflicting memories, we hope to inform research into treating the maladaptation of this process such as in PTSD.”

Funding: The research was supported by the Royal Society, Wellcome and Leverhulme Trust.

About this memory and neuroscience research news

Author: Chris Lane

Source: UCL

Contact: Chris Lane – UCL

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Conflict during learning reconfigures the neural representation of positive valence and approach behaviour” by Arantza Barrios et al. Current Biology

Abstract

Conflict during learning reconfigures the neural representation of positive valence and approach behaviour

Punishing and rewarding experiences can change the valence of sensory stimuli and guide animal behavior in opposite directions, resulting in avoidance or approach. Often, however, a stimulus is encountered with both positive and negative experiences.

How is such conflicting information represented in the brain and resolved into a behavioral decision?

We address this question by dissecting a circuit for sexual conditioning in C. elegans. In this learning paradigm, an odor is conditioned with both a punishment (starvation) and a reward (mates), resulting in odor approach.

We find that negative and positive experiences are both encoded by the neuropeptide pigment dispersing factor 1 (PDF-1) being released from, and acting on, different neurons. Each experience creates a distinct memory in the circuit for odor processing.

This results in the sensorimotor representation of the odor being different in naive and sexually conditioned animals, despite both displaying approach.

Our results reveal that the positive valence of a stimulus is not represented in the activity of any single neuron class but flexibly represented within the circuit according to the experiences and predictions associated with the stimulus.