Summary: Emerging research suggests that chronic inflammation, rather than neurotransmitter deficiencies alone, may be a major factor behind depression, reshaping traditional views of the condition. This insight links inflammation, both in the body and brain, to depressive symptoms, explaining why some patients don’t respond to conventional antidepressants.

Studies reveal that stress can trigger immune responses that activate and later damage microglial cells in the brain, worsening depressive symptoms over time. These findings support a more personalized treatment approach, where some patients might benefit from anti-inflammatory therapies rather than standard antidepressants.

For patients with treatment-resistant depression or those exposed to chronic stress, inflammation-targeted treatments offer a hopeful new direction. The research underscores the potential of addressing immune dysfunctions to manage depression effectively.

Key Facts:

- Chronic inflammation may drive depressive symptoms, challenging traditional theories.

- Prolonged stress activates and later damages brain microglial cells, worsening depression.

- Personalized treatments targeting inflammation could benefit patients unresponsive to standard antidepressants.

Source: Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Depression, recognized as the leading cause of disability worldwide, affects nearly one in six people over their lifetimes. Despite decades of research, much remains unknown about the biological mechanisms underlying this debilitating condition.

Professor Raz Yirmiya, a pioneering researcher in the field of inflammation and depression from the Department of Psychology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has recently published a comprehensive review in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, offering new insights that challenge long-held beliefs and open pathways toward personalized treatment.

Traditional theories of depression have focused on neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine, suggesting that a deficiency in these brain chemicals may lead to depressive symptoms. While widely accepted, these theories have failed to explain why a significant portion of patients do not respond to conventional antidepressants.

Over the last 30 years, Professor Yirmiya’s research, along with work from others, has pointed to a different culprit: chronic inflammation, both in the body and the brain.

“In many individuals, depression results from inflammatory processes,” explains Professor Yirmiya, who was one of the first researchers to draw connections between immune system dysfunction and depression in the 1990s.

In his latest review, he carefully analyzed the 100 most-cited papers in the field, creating what he calls a “panoramic view” of the complex interactions between inflammation and depressive symptoms.

Research dating back to the 1980s has highlighted that depressed individuals often exhibit compromised immune functions. Surprisingly, certain immune-boosting treatments for cancer and hepatitis, which induce an inflammatory response, have been found to cause severe depressive symptoms in patients, offering a glimpse into the immune system’s role in mental health.

Yirmiya’s own experiments further established a mechanistic link between inflammation and mood, showing that healthy individuals injected with low doses of immune-stimulating agents exhibit a temporary depressive state, which can be prevented by either anti-inflammatory or conventional antidepressant treatments.

Professor Yirmiya and colleagues have also shown that stress—often a major trigger for depression—can prompt inflammatory processes, impacting the brain’s microglia cells, which are the representatives of the immune system in the brain.

Their recent findings reveal that stress-related inflammatory responses may initially activate microglia, but prolonged stress eventually exhausts and damages them, thereby sustaining or worsening depression.

“This dynamic cycle of activation and degeneration of microglia mirrors the progression of depression itself,” says Yirmiya.

The review also highlights studies that suggest specific groups, such as elderly individuals, those with physical illnesses, individuals who suffered from early childhood adversity, and patients with treatment-resistant depression, are particularly susceptible to inflammation-linked depression.

The findings reveal the necessity of anti-inflammatory treatments for certain patients and for microglia-boosting treatments to other patients, indicating that a personalized approach to treatment may prove more effective than traditional one-size-fits-all antidepressant therapy.

Professor Yirmiya concludes, “The research findings from the past three decades underscore the critical role of the immune system in depression.

“Moving forward, a personalized medicine approach—tailoring treatment based on the patient’s specific inflammatory profile—offers hope to millions of sufferers who find little relief in standard therapies. By embracing these advancements, we’re not just treating symptoms; we’re addressing the underlying causes.”

This study not only sheds light on the origins of depression but also sets the stage for future therapeutic approaches, particularly those that target the immune system. Through further investigation, Professor Yirmiya aims to inspire a new wave of treatments designed to replace despair with hope for those suffering from depression.

About this depression and mental health research news

Author: Raz Yirmiya

Source: Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Contact: Raz Yirmiya – Hebrew University of Jerusalem

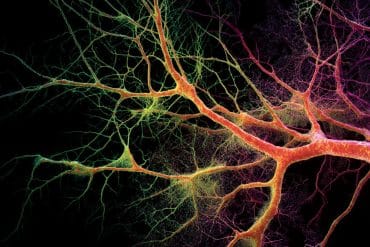

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“The inflammatory underpinning of depression: An historical perspective” by Raz Yirmiya. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity

Abstract

The inflammatory underpinning of depression: An historical perspective

Over the last thirty years, substantial evidence has accumulated in support of the hypothesis that dysregulation of inflammatory processes plays a critical role in the pathophysiology of depression.

This review traces the evolution of research supporting this link, discussing key findings from several major investigative fronts: Alterations in inflammatory markers associated with depression; Mood changes following the exogenous administration of inflammatory challenges; The anti-inflammatory properties of traditional antidepressants and the promising antidepressant effects of anti-inflammatory drugs.

Additionally, it explores how inflammatory processes interact with specific brain regions and neurochemical systems to drive depressive pathology.

A thorough analysis of the 100 most-cited experimental studies on the topic ensures a comprehensive, transparent and unbiased collection of references.

This methodological approach offers a panoramic view of the inflammation-depression nexus, shedding light on the complexity of its mechanisms and their connections to psychiatric categorizations, symptoms, demographics, and life events.

Synthesizing insights from this extensive research, the review presents an integrative model of the biological foundations of inflammation-associated depression.

It posits that we have reached a critical juncture where the translation of this knowledge into personalized immunomodulatory treatments for depression is not just possible, but imperative.