Summary: New research shows that severe Covid-19 infection can cause inflammation in the brainstem, potentially leading to prolonged symptoms like fatigue, breathlessness, and anxiety. Using ultra-high-resolution 7-Tesla MRI scanners, scientists observed specific brainstem areas associated with these symptoms, highlighting how immune response post-infection might affect brain health.

This inflammation may impact both physical and mental health, as brainstem abnormalities were linked to higher levels of anxiety and depression in patients. The findings offer valuable insights for understanding long-term Covid effects and could improve treatment approaches for conditions related to brainstem inflammation.

Key Facts

- Severe Covid-19 can cause persistent inflammation in brainstem regions.

- Inflammation in the brainstem is associated with fatigue, breathlessness, and anxiety.

- 7-Tesla MRI scans provide detailed insights into immune response in the brainstem.

Source: University of Cambridge

Damage to the brainstem – the brain’s ‘control centre’ – is behind long-lasting physical and psychiatric effects of severe Covid-19 infection, a study suggests.

Using ultra-high-resolution scanners that can see the living brain in fine detail, researchers from the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford were able to observe the damaging effects Covid-19 can have on the brain.

The study team scanned the brains of 30 people who had been admitted to hospital with severe Covid-19 early in the pandemic, before vaccines were available. The researchers found that Covid-19 infection damages the region of the brainstem associated with breathlessness, fatigue and anxiety.

The powerful MRI scanners used for the study, known as 7-Tesla or 7T scanners, can measure inflammation in the brain. Their results, published in the journal Brain, will help scientists and clinicians understand the long-term effects of Covid-19 on the brain and the rest of the body.

Although the study was started before the long-term effects of Covid was recognised, it will help to better understand this condition.

The brainstem, which connects the brain to the spinal cord, is the control centre for many basic life functions and reflexes. Clusters of nerve cells in the brainstem, known as nuclei, are responsible for regulating and processing essential bodily functions such as breathing, heart rate, pain and blood pressure.

“Things happening in and around the brainstem are vital for quality of life, but it had been impossible to scan the inflammation of the brainstem nuclei in living people, because of their tiny size and difficult position.” said first author Dr Catarina Rua, from the Department of Clinical Neurosciences.

“Usually, scientists only get a good look at the brainstem during post-mortem examinations.”

“The brainstem is the critical junction box between our conscious selves and what is happening in our bodies,” said Professor James Rowe, also from the Department of Clinical Neurosciences, who co-led the research.

“The ability to see and understand how the brainstem changes in response to Covid-19 will help explain and treat the long term effects more effectively.”

In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, before effective vaccines were available, post-mortem studies of patients who had died from severe Covid-19 infections showed changes in their brainstems, including inflammation.

Many of these changes were thought to result from a post-infection immune response, rather than direct virus invasion of the brain.

“People who were very sick early in the pandemic showed long-lasting brain changes, likely caused by an immune response to the virus. But measuring that immune response is difficult in living people,” said Rowe. “Normal hospital type MRI scanners can’t see inside the brain with the kind of chemical and physical detail we need.”

“But with 7T scanners, we can now measure these details. The active immune cells interfere with the ultra-high magnetic field, so that we’re able to detect how they are behaving,” said Rua.

“Cambridge was special because we were able to scan even the sickest and infectious patients, early in the pandemic.”

Many of the patients admitted to hospital early in the pandemic reported fatigue, breathlessness and chest pain as troubling long-lasting symptoms. The researchers hypothesised these symptoms were in part the result of damage to key brainstem nuclei, damage which persists long after Covid-19 infection has passed.

The researchers saw that multiple regions of the brainstem, in particular the medulla oblongata, pons and midbrain, showed abnormalities consistent with a neuroinflammatory response. The abnormalities appeared several weeks after hospital admission, and in regions of the brain responsible for controlling breathing.

“The fact that we see abnormalities in the parts of the brain associated with breathing strongly suggests that long-lasting symptoms are an effect of inflammation in the brainstem following Covid-19 infection,” said Rua.

“These effects are over and above the effects of age and gender, and are more pronounced in those who had had severe Covid-19.”

In addition to the physical effects of Covid-19, the 7T scanners provided evidence of some of the psychiatric effects of the disease. The brainstem monitors breathlessness, as well as fatigue and anxiety.

Mental health is intimately connected to brain health, and patients with the most marked immune response also showed higher levels of depression and anxiety,” said Rowe.

“Changes in the brainstem caused by Covid-19 infection could also lead to poor mental health outcomes, because of the tight connection between physical and mental health.”

The researchers say the results could aid in the understanding of other conditions associated with inflammation of the brainstem, like MS and dementia. The 7T scanners could also be used to monitor the effectiveness of different treatments for brain diseases.

“This was an incredible collaboration, right at the peak of the pandemic, when testing was very difficult, and I was amazed how well the 7T scanners worked,” said Rua. “I was really impressed with how, in the heat of the moment, the collaboration between lots of different researchers came together so effectively.”

Funding: The research was supported in part by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, and the University of Oxford COVID Medical Sciences Division Rapid Response Fund.

About this neurology and Long-COVID research news

Author: Sarah Collins

Source: University of Cambridge

Contact: Sarah Collins – University of Cambridge

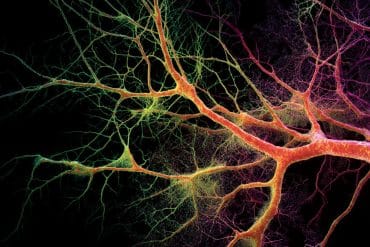

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: The findings will appear in Brain