Summary: A new study reports computer simulations have helped to identify the drug’s binding sites.

Source: Carnegie Mellon University.

As many as one out of four adults who suffer from epilepsy do not respond to any available drugs.

That makes the search for effective new anti-seizure medications vital, and Carnegie Mellon University chemist Maria Kurnikova is playing a key role in that quest.

Kurnikova, an associate professor of chemistry, is part of a team that published a paper in the journal Neuron that shows how one class of drugs blocks the spread of out-of-control electrical signals in the brain during a seizure.

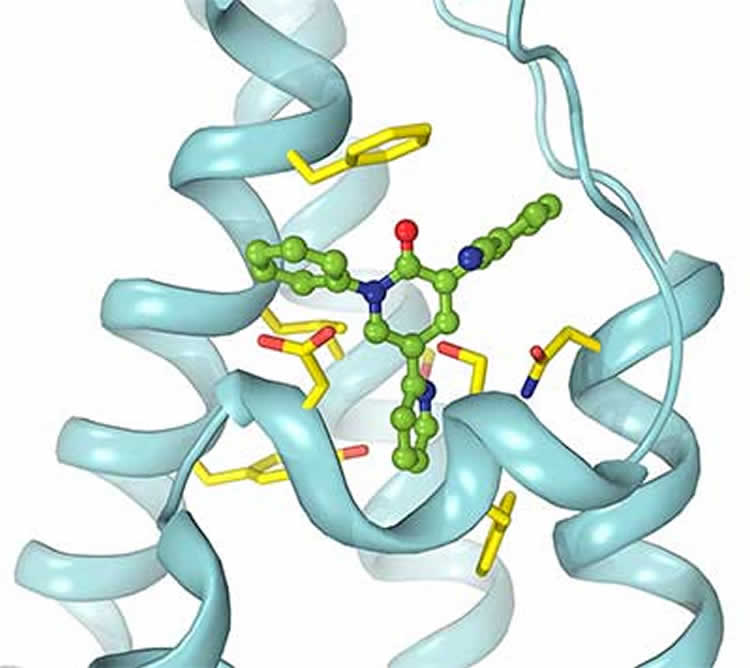

A team led by Alexander Sobolevsky at Columbia University used crystallography and other techniques to visualize how the drugs block signals in the AMPA brain receptor, which is one of the main gateways for electrical signals as they propagate through the brain.

In epilepsy, the AMPA receptors appear to be hypersensitive, opening the way for the firestorm of electrical impulses that comprise a seizure.

Kurnikova, who specializes in computer simulations of how molecules interact in the brain, helped identify the binding sites for the drugs, supporting the idea that the medications sit like a wedge in the AMPA receptor and keep signals from getting through.

Because AMPA receptors are necessary for normal brain function, any drug that blocks some of those receptors can cause certain side effects, including sleepiness, nausea and headaches.

“Basically what you want to do with the drugs is create a situation where the excitation [in the brain] is not quite so easy to achieve, so you might create some sleepiness,” Kurnikova says. “But if it’s a question of sleepiness versus epilepsy, you would take the sleepiness.”

In the future, the work being done by Kurnikova’s and Sobolevsky’s team may be able to tweak the anti-seizure drugs to reduce the side effects. Sobolevsky notes that this class of drugs, which includes a commercially available medication known as perampanel, already “is way safer than other types of medications,” and the new study suggests that “by changing the design of the drug we can make it even safer.”

Sobolevsky’s group used techniques like crystallography and electrophysiological measurements to visualize the shape of the drug and receptor molecules, and to show how the drug changes the receptor’s function. Kurnikova enhanced the findings by using software programs that simulate the precise way that the drug molecules bind to the receptor.

To do that, the computer program has to examine millions of different configurations between the drug and the receptor, and that requires enormous computing power. In her laboratory at the Mellon Institute, Kurnikova uses computers that are much more powerful than what was available when she started this kind of work several years ago.

One reason she can simulate molecules and proteins so much better today is the advances made by the gaming industry. By developing powerful graphics cards in computers to create realistic animations in video games, computer manufacturers have enabled her to buy a $2,000 PC that can accomplish the work of 20 computers just 10 years ago.

She also makes use of a special high-speed computer designed specifically for molecular simulations. Named ANTON, the computer was created by the D.E. Shaw Co. and is housed at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center. Because it is in demand by researchers around the nation, she must compete for time on ANTON by applying to the National Academy of Sciences.

This year, she was allotted enough time to simulate 30 microseconds in the life of an AMPA receptor. The ANTON simulation was 100 times faster than what she has in-house.

Kurnikova grew up in Norilsk, a mining city in Russia near the Arctic Ocean where the average high temperature in winter is less than 5 degrees. Her parents were both engineers who later moved to Moscow, where she got her master’s from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. She then obtained her Ph.D. in theoretical chemistry from the University of Pittsburgh, and went on to do research and teaching in Israel and at Marquette University before joining the Carnegie Mellon faculty in 2003. She was promoted to associate professor in 2009.

Her daughter is a Carnegie Mellon graduate, and is currently a graduate student in neuroscience at the University of California at San Diego.

If Sobolevsky and Kurnikova can get additional funding for their epilepsy research, they hope to design new drugs that could block seizures with even fewer side effects. While there are a few medications that have been developed this way, she says, “such rational drug design is difficult. Drug companies usually try everything they can think of and see what sticks.”

Working together, Sobolevsky says, “we will propose new drugs, and if we are right about our assumptions, some of our new proposed drugs should be better.”

Source: Mark Roth – Carnegie Mellon University

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Laboratory of Alexander Sobolevsky, PhD/Columbia University Medical Center.

Original Research: Abstract for “Structural Bases of Noncompetitive Inhibition of AMPA-Subtype Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors by Antiepileptic Drugs” by Maria V. Yelshanskaya, Appu K. Singh, Jared M. Sampson, Chamali Narangoda, Maria Kurnikova, and Alexander I. Sobolevsky in Neuron. Published online September 8 2016 doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.012

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Carnegie Mellon University “Study Shows How Epilepsy Drugs Block Electrical Signals in the Brain.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 29 November 2016.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/brain-signal-epilepsy-drug-5628/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Carnegie Mellon University (2016, November 29). Study Shows How Epilepsy Drugs Block Electrical Signals in the Brain. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved November 29, 2016 from https://neurosciencenews.com/brain-signal-epilepsy-drug-5628/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Carnegie Mellon University “Study Shows How Epilepsy Drugs Block Electrical Signals in the Brain.” https://neurosciencenews.com/brain-signal-epilepsy-drug-5628/ (accessed November 29, 2016).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Structural Bases of Noncompetitive Inhibition of AMPA-Subtype Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors by Antiepileptic Drugs

Highlights

•Crystal structures reveal binding of antiepileptic drugs to AMPA receptors

•Binding occurs at a novel allosteric site on the ion channel extracellular side

•The drugs are noncompetitive inhibitors acting as wedges to prevent channel opening

•Binding site molecular composition provides a template for synthesis of new drugs

Summary

Excitatory neurotransmission plays a key role in epileptogenesis. Correspondingly, AMPA-subtype ionotropic glutamate receptors, which mediate the majority of excitatory neurotransmission and contribute to seizure generation and spread, have emerged as promising targets for epilepsy therapy. The most potent and well-tolerated AMPA receptor inhibitors act via a noncompetitive mechanism, but many of them produce adverse side effects. The design of better drugs is hampered by the lack of a structural understanding of noncompetitive inhibition. Here, we report crystal structures of the rat AMPA-subtype GluA2 receptor in complex with three noncompetitive inhibitors. The inhibitors bind to a novel binding site, completely conserved between rat and human, at the interface between the ion channel and linkers connecting it to the ligand-binding domains. We propose that the inhibitors stabilize the AMPA receptor closed state by acting as wedges between the transmembrane segments, thereby preventing gating rearrangements that are necessary for ion channel opening.

“Structural Bases of Noncompetitive Inhibition of AMPA-Subtype Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors by Antiepileptic Drugs” by Maria V. Yelshanskaya, Appu K. Singh, Jared M. Sampson, Chamali Narangoda, Maria Kurnikova, and Alexander I. Sobolevsky in Neuron. Published online September 8 2016 doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.012