Summary: According to researchers, those who live in colder regions with less daytime sun light drink more alcohol than those who live in warm areas. Climate, researchers say, may impact the prevalence of alcoholism and alcoholic cirrhosis.

Source: University of Pittsburgh.

Where you live could influence how much you drink. According to new research from the University of Pittsburgh Division of Gastroenterology, people living in colder regions with less sunlight drink more alcohol than their warm-weather counterparts.

The study, recently published online in Hepatology, found that as temperature and sunlight hours dropped, alcohol consumption increased. Climate factors also were tied to binge drinking and the prevalence of alcoholic liver disease, one of the main causes of mortality in patients with prolonged excessive alcohol use.

“It’s something that everyone has assumed for decades, but no one has scientifically demonstrated it. Why do people in Russia drink so much? Why in Wisconsin? Everybody assumes that’s because it’s cold,” said senior author Ramon Bataller, M.D., Ph.D., chief of hepatology at UPMC, professor of medicine at Pitt, and associate director of the Pittsburgh Liver Research Center. “But we couldn’t find a single paper linking climate to alcoholic intake or alcoholic cirrhosis. This is the first study that systematically demonstrates that worldwide and in America, in colder areas and areas with less sun, you have more drinking and more alcoholic cirrhosis.”

Alcohol is a vasodilator – it increases the flow of warm blood to the skin, which is full of temperature sensors – so drinking can increase feelings of warmth. In Siberia that could be pleasant, but not so much in the Sahara.

Drinking also is linked to depression, which tends to be worse when sunlight is scarce and there’s a chill in the air.

Using data from the World Health Organization, the World Meteorological Organization and other large, public data sets, Bataller’s group found a clear negative correlation between climate factors – average temperature and sunlight hours – and alcohol consumption, measured as total alcohol intake per capita, percent of the population that drinks alcohol, and the incidence of binge drinking.

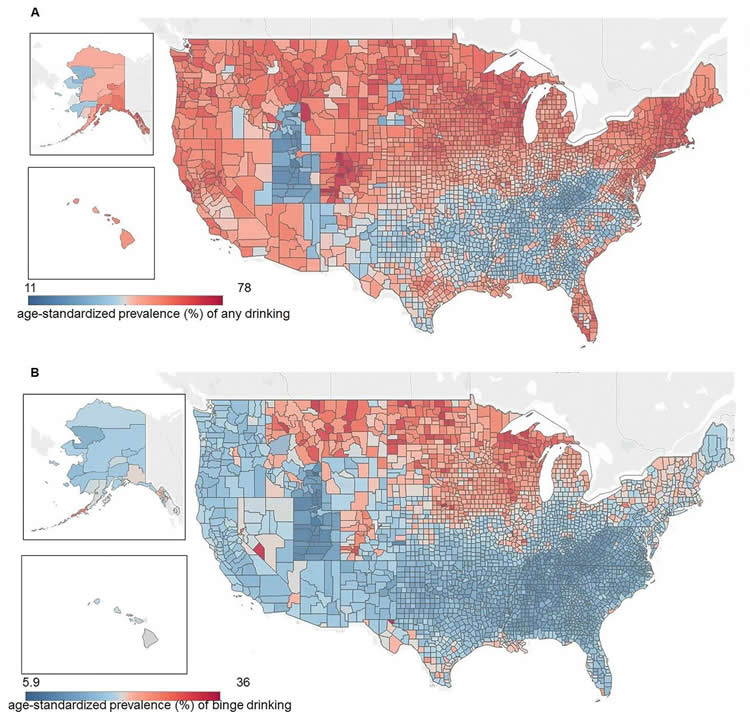

The researchers also found evidence that climate contributed to a higher burden of alcoholic liver disease. These trends were true both when comparing across countries around the world and also when comparing across counties within the United States.

“It’s important to highlight the many confounding factors,” said lead author Meritxell Ventura-Cots, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher at the Pittsburgh Liver Research Center. “We tried to control for as many as we could. For instance, we tried to control for religion and how that influences alcohol habits.”

With much of the desert-dwelling Arab world abstaining from alcohol, it was critical to verify that the results would hold up even when excluding these Muslim-majority countries. Likewise, within the U.S., Utah has regulations that limit alcohol intake, which have to be taken into account.

When looking for patterns of cirrhosis, the researchers had to control for health factors that might exacerbate the effects of alcohol on the liver–like viral hepatitis, obesity and smoking.

In addition to settling an age-old debate, this research suggests that policy initiatives aimed at reducing the burden of alcoholism and alcoholic liver disease should target geographic areas where alcohol is more likely to be problematic.

Additional authors on this study include Ariel Watts, B.S., Neil Shah, M.D., Peter McCann, M.D., and A. Sidney Barritt IV, M.D., all of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Monica Cruz-Lemini, M.D., Ph.D., of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México at Juriquilla; Jose Altamirano, M.D., of Hospital Quirónsalud in Barcelona; Juan Abraldes, M.D., from The University of Alberta; Nambi Ndugga, M.P.H., of Harvard; and Anant Jain, M.D., Samhita Ravi, and Carlos Fernández-Carrillo, M.D., Ph.D., all of Pitt.

Funding: This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awards U01AA021908 and U01AA020821, the Mexican National Council for Science and Technology and the Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver.

Source: Erin Hare – University of Pittsburgh

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Ventura Cots et al. (2018).

Original Research: Abstract for “Colder weather and fewer sunlight hours increase alcohol consumption and alcoholic cirrhosis worldwide” by Meritxell Ventura‐Cots, Ariel E. Watts, Monica Cruz‐Lemini, Neil D. Shah, Nambi Ndugga, Peter McCann, A. Sidney Barritt IV, Anant Jain, Samhita Ravi, Carlos Fernandez‐Carrillo, Juan G. Abraldes, Jose Altamirano, and Ramon Bataller in Hepatology. Published October 16 2018.

doi:10.1002/hep.30315

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]University of Pittsburgh”Colder, Darker Climates Increase Alcohol Consumption and Liver Disease.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 14 November 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/alcohol-cold-climate-10201/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]University of Pittsburgh(2018, November 14). Colder, Darker Climates Increase Alcohol Consumption and Liver Disease. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved November 14, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/alcohol-cold-climate-10201/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]University of Pittsburgh”Colder, Darker Climates Increase Alcohol Consumption and Liver Disease.” https://neurosciencenews.com/alcohol-cold-climate-10201/ (accessed November 14, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Colder weather and fewer sunlight hours increase alcohol consumption and alcoholic cirrhosis worldwide

Risk of alcoholic cirrhosis is determined by genetic and environmental factors. Although it is generally accepted that colder weather predisposes to alcohol misuse, no studies have investigated its impact on alcohol intake and alcoholic cirrhosis. We aimed to investigate if climate has a causal effect on alcohol consumption and its weight on alcoholic cirrhosis. We collected extensive data from 193 sovereign countries as well as 50 states and 3,144 counties in the United States. Data sources included World Health Organization, World Meteorological Organization, and the Institute on Health Metrics and Evaluation. Climate parameters comprised Koppen‐Geiger classification, average annual sunshine hours, and average annual temperature. Alcohol consumption data, pattern of drinking, health indicators, and alcohol‐attributable fraction (AAF) of cirrhosis were obtained. The global cohort revealed an inverse correlation between mean average temperature and average annual sunshine hours with liters of annual alcohol consumption per capita (Spearman’s rho −0.5 and −0.57, respectively). Moreover, the percentage of heavy episodic drinking and total drinkers among population inversely correlated with temperature −0.45 and −0.49 (P < 0.001) and sunshine hours −0.39 and −0.57 (P < 0.001). Importantly, AAF was inversely correlated with temperature −0.45 (P < 0.001) and sunshine hours −0.6 (P < 0.001). At a global level, all included parameters in the univariable and multivariable analysis showed an association with liters of alcohol consumption and drinkers among population once adjusted by potential confounders. In the multivariate analysis, liters of alcohol consumption associated with AAF. In the United States, colder climates showed a positive correlation with the age‐standardized prevalence of heavy and binge drinkers.