Summary: Researchers suggest older people may be less likely to take risks due to declining dopamine levels.

Source: UCL.

Older people are less willing to take risks for potential rewards and this may be due to declining levels of dopamine in the brain, finds a new UCL study of over 25,000 people funded by Wellcome.

The study, published in Current Biology, found that older people were less likely to choose risky gambles to win more points in a smartphone app called The Great Brain Experiment. However, they were no different to younger participants when it came to choosing risky gambles to avoid losing points. It is widely believed that older people don’t take risks, but the study shows exactly what kind of risks older people avoid.

The steady decline in risky choices with age matches a steady decline in dopamine levels. Throughout adult life, dopamine levels fall by up to 10% every decade.

Dopamine is a chemical in the brain involved in predicting which actions will lead to rewards, and the researchers previously found that volunteers chose significantly more risky gambles to win more money when given a drug that boosted dopamine levels.

“As we age, our dopamine levels naturally decline which could explain why we are less likely to seek rewards,” explains lead author Dr Robb Rutledge (UCL Institute of Neurology and Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research). “The effects we saw in the experiment may be due to dopamine decline, since age was associated with only one type of risk taking and mirrored the known effects of dopamine drugs on decision making. Older people were not more risk-averse overall, and they didn’t make more mistakes than young people did. Older people were simply less attracted to big rewards and this made them less willing to take risks to try to get them.”

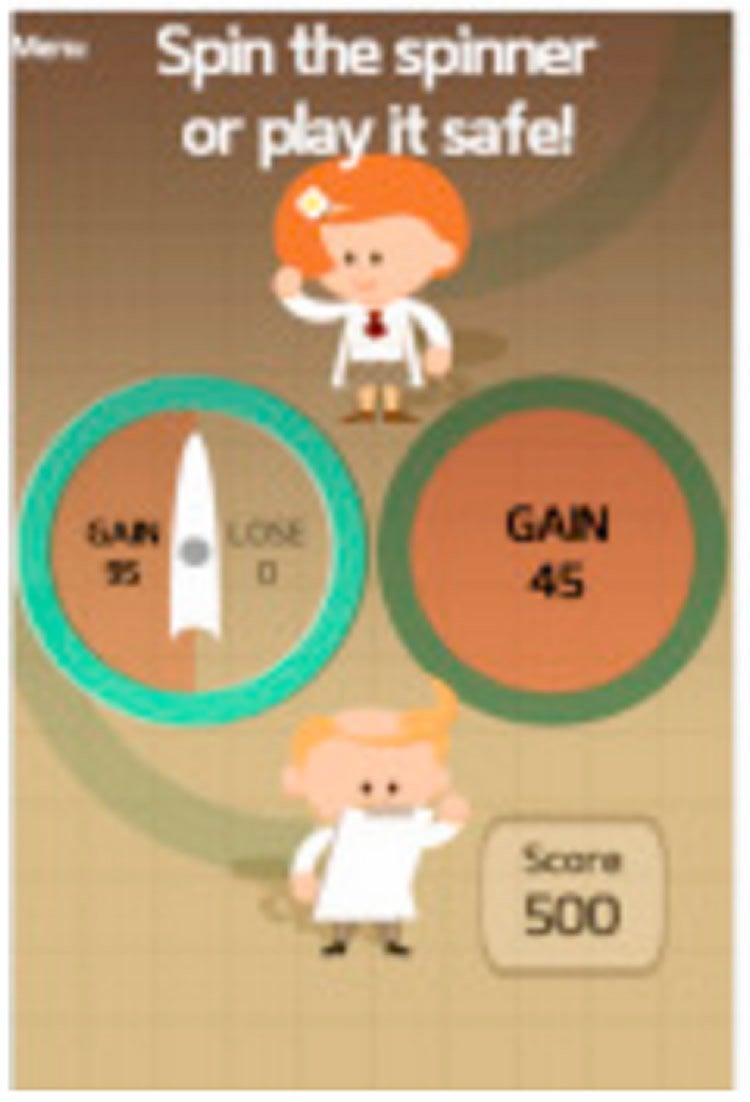

The experiment involved 25,189 smartphone users aged 18-69 who played a game in The Great Brain Experiment smartphone app that involves gambling for points.* In the game, players start with 500 points and aim to win as many points as possible in thirty different trials where they must choose between a safe option and a risky 50/50 gamble.

In the ‘gain’ trials, players can either choose a guaranteed number of points or a 50/50 chance of winning more points or gaining nothing. The ‘loss’ trials are the same in reverse, where players can lose a fixed number of points or gamble with a chance of losing more points or nothing. In the ‘mixed’ trials, players can choose zero points or to gamble with a chance of either gaining or losing points.

On average, all age groups chose to gamble in approximately 56% of the loss trials and 67% of the mixed trials. In the gain trials, 18-24 year olds gambled in 72% of trials and this fell steadily to 64% in the 60-69 age group.

This study also involved mathematical equations which allowed the authors to make specific predictions for how loss of dopamine would affect decision making.

“A loss of dopamine may explain why older people are less attracted to the promise of potential rewards,” says Dr Rutledge. “Decisions involving potential losses were unaffected and this may be because different processes important for losses are not affected by ageing.

“Political campaigners often frame voting decisions negatively, for example saying that UK households would be £4,300 worse off if the UK decides later this month to leave the EU rather than £4,300 better off if the UK decides to remain part of the EU. They already know that negative messaging helps to persuade older people, whereas a more optimistic approach that emphasizes large potential rewards might appeal more to younger people who are less likely to vote. Our new findings offer a potential neuroscientific explanation, suggesting that a natural decline in dopamine with age might make people less receptive to the positive approach than they would have been when they were younger.”

Dr Raliza Stoyanova, from the Neuroscience and Mental Health team at Wellcome, which funded the study, says: “This study is an excellent example of the use of digital technology to produce new and robust insights into the workings of the brain. Smartphone apps allowed the researchers to capture decision-making outside of typical ‘lab’ settings, and to reach more people from varied backgrounds than is typically possible.

“It will be exciting to see what else the data generated from the Great Brain Experiment will reveal about risk and decision-making, as well as other complex brain processes like memory and attention.”

Note from researchers: If you would like to try the game for yourself, you can download The Great Brain Experiment for iPhone or Android and play the ‘What makes me happy?’ game. There are eight games in total and playing them contributes to cognitive science research.

Funding: The study was supported by Wellcome.

Source: Harry Dayantis – UCL

Image Source: This NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to the researchers/Current Biology.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Risk Taking for Potential Reward Decreases across the Lifespan” by Robb B. Rutledge, Peter Smittenaar, Peter Zeidman, Harriet R. Brown, Rick A. Adams, Ulman Lindenberger, Peter Dayan, and Raymond J. Dolan in Current Biology. Published online June 2 2026 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.017

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]UCL. “Declining Dopamine May Explain Why Older People Take Less Risks.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 2 June 2026.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/aging-risk-dopamine-4359/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]UCL. (2026, June 2). Declining Dopamine May Explain Why Older People Take Less Risks. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved June 2, 2026 from https://neurosciencenews.com/aging-risk-dopamine-4359/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]UCL. “Declining Dopamine May Explain Why Older People Take Less Risks.” https://neurosciencenews.com/aging-risk-dopamine-4359/ (accessed June 2, 2026).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Risk Taking for Potential Reward Decreases across the Lifespan

Highlights

•Aging reduced risk taking for potential gains but not potential losses

•Computational models revealed that a Pavlovian influence of reward decreased with age

•Age-related dopamine decline can explain the decrease in Pavlovian biases

Summary

The extent to which aging affects decision-making is controversial. Given the critical financial decisions that older adults face (e.g., managing retirement funds), changes in risk preferences are of particular importance [ 1 ]. Although some studies have found that older individuals are more risk averse than younger ones [ 2–4 ], there are also conflicting results, and a recent meta-analysis found no evidence for a consistent change in risk taking across the lifespan [ 5 ]. There has as yet been little examination of one potential substrate for age-related changes in decision-making, namely age-related decline in dopamine, a neuromodulator associated with risk-taking behavior. Here, we characterized choice preferences in a smartphone-based experiment (n = 25,189) in which participants chose between safe and risky options. The number of risky options chosen in trials with potential gains but not potential losses decreased gradually over the lifespan, a finding with potentially important economic consequences for an aging population. Using a novel approach-avoidance computational model, we found that a Pavlovian attraction to potential reward declined with age. This Pavlovian bias has been linked to dopamine, suggesting that age-related decline in this neuromodulator could lead to the observed decrease in risk taking.

“Risk Taking for Potential Reward Decreases across the Lifespan” by Robb B. Rutledge, Peter Smittenaar, Peter Zeidman, Harriet R. Brown, Rick A. Adams, Ulman Lindenberger, Peter Dayan, and Raymond J. Dolan in Current Biology. Published online June 2 2026 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.017