Summary: A new study reports Zika may be transmitted both sexually and orally.

Source: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Evidence suggests virus may be sexually, orally transmitted.

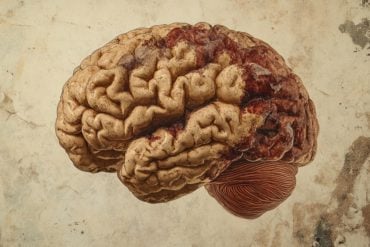

Though first documented 70 years ago, the Zika virus was poorly understood when it burst onto the scene in the Americas in 2015. In one of the first and largest studies of its kind, a research team lead by virologists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) has characterized the progression of two strains of the viral infection. The study, published online this week in Nature Medicine, revealed Zika’s rapid infection of the brain and nervous tissues, and provided evidence of risk for person-to-person transmission.

“We found, initially, that the virus replicated very rapidly and was cleared from the blood in most animals within ten days,” said corresponding author James B. Whitney, PhD, a principal investigator at the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research (CVVR) at BIDMC. “Nevertheless, we observed viral shedding in other bodily fluids such as spinal fluid, saliva, urine and semen, up to three weeks after the initial infection was already cleared.”

Whitney and colleagues infected 36 rhesus and cynomolgus macaques with strains of the Zika virus derived from Puerto Rico and Thailand. Over the next four weeks, the scientists tested blood, tissues, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and mucosal secretions for the presence of Zika virus, as well as monitored the immune response during early infection. Their data shed new light on the previously little-studied virus, and might help explain how Zika causes the devastating neurological complications seen in adults and unborn babies.

“Of particular concern, we saw extraordinarily high levels of Zika virus in the brain of some of the animals – the cerebellum, specifically – soon after infection,” said Whitney, who is also assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and an associate member of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard. “Only one in five adults has noticeable symptoms of infection. However, if our data translate to humans, there may be need for enhanced clinical vigilance for any persons presenting with unusual neurological symptoms, and they should be tested for Zika infection.”

Like in humans, Zika infection in the experimental primates appeared relatively mild, producing fever and an increase in blood cells associated with the immune response. All recovered without intervention. But while the virus was cleared from the blood stream within ten days, the researchers observed Zika virus in urine as soon as two days after infection in some subjects. By the third day after infection, Zika was detectable in the saliva of up to half of the subjects, where it remained until the study ended at 28 days after infection.

“This underscores the need to understand what’s happening in anatomic reservoirs where the virus may hide for a long time,” said Whitney.

Early in infection, the researchers found high levels of Zika in the genital tracts of both sexes. Zika remained detectable in semen and in uterine tissues until the end of the study. The first sexually transmitted case of Zika in humans was documented in 2007, but these new findings suggest transmission may occur long after Zika symptoms – if they ever appeared – resolve. Because the researchers found high levels of the virus in semen and uterus, but little in vaginal secretions, the findings may also illuminate sexual transmission of Zika.

“We found that male-to-female transmission may be easier, while female-to-male may be less likely,” said Whitney. “Nonetheless, the high levels of Zika we observed in the uterus underscore the danger to a developing fetus.”

The new study also highlights the need for the rapid development of vaccines and therapies against the virus. Zika infection in pregnant women has been shown to lead to fetal microcephaly and other major birth defects. The World Health Organization declared the virus epidemic a global public health emergency on February 1, 2016.

Study coauthors include: Christa E. Osuna (first author) and So-Yun Lim, both of the CVVR at BIDMC; Claire Deleage of Leidos Biomedical Research at Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research,; Bryan D. Griffin, Derek Stein, Lukas T. Schroeder, Robert Omage, Ma Luo and David Safronetz of the National Microbiology Laboratory, Canada; Katharine Best, Peter T. Hraber, Erwing Fabian Cardozo Ojeda and Alan S. Perelson of Los Alamos National Laboratory; Hanne Andersen-Elyard and Mark G. Lewis of Bioqual; Scott Huang, Dana L. Vanlandingham and Stephen Higgs of Biosecurity Research Institute, Kansas State University.

Source: Jacqueline Mitchell – Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Abstract for “Zika viral dynamics and shedding in rhesus and cynomolgus macaques” by Christa E Osuna, So-Yon Lim, Claire Deleage, Bryan D Griffin, Derek Stein, Lukas T Schroeder, Robert Omage, Katharine Best, Ma Luo, Peter T Hraber, Hanne Andersen-Elyard, Erwing Fabian Cardozo Ojeda, Scott Huang, Dana L Vanlandingham, Stephen Higgs, Alan S Perelson, Jacob D Estes, David Safronetz, Mark G Lewis and James B Whitney in Nature Medicine. Published online October 3 2016 doi:10.1038/nm.4206

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center “New Insight into Course and Transmission of Zika.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 6 October 2016.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/zika-transmission-neurology-5226/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (2016, October 6). New Insight into Course and Transmission of Zika. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved October 6, 2016 from https://neurosciencenews.com/zika-transmission-neurology-5226/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center “New Insight into Course and Transmission of Zika.” https://neurosciencenews.com/zika-transmission-neurology-5226/ (accessed October 6, 2016).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Zika viral dynamics and shedding in rhesus and cynomolgus macaques

Infection with Zika virus has been associated with serious neurological complications and fetal abnormalities. However, the dynamics of viral infection, replication and shedding are poorly understood. Here we show that both rhesus and cynomolgus macaques are highly susceptible to infection by lineages of Zika virus that are closely related to, or are currently circulating in, the Americas. After subcutaneous viral inoculation, viral RNA was detected in blood plasma as early as 1 d after infection. Viral RNA was also detected in saliva, urine, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and semen, but transiently in vaginal secretions. Although viral RNA during primary infection was cleared from blood plasma and urine within 10 d, viral RNA was detectable in saliva and seminal fluids until the end of the study, 3 weeks after the resolution of viremia in the blood. The control of primary Zika virus infection in the blood was correlated with rapid innate and adaptive immune responses. We also identified Zika RNA in tissues, including the brain and male and female reproductive tissues, during early and late stages of infection. Re-infection of six animals 45 d after primary infection with a heterologous strain resulted in complete protection, which suggests that primary Zika virus infection elicits protective immunity. Early invasion of Zika virus into the nervous system of healthy animals and the extent and duration of shedding in saliva and semen underscore possible concern for additional neurologic complications and nonarthropod-mediated transmission in humans.

“Zika viral dynamics and shedding in rhesus and cynomolgus macaques” by Christa E Osuna, So-Yon Lim, Claire Deleage, Bryan D Griffin, Derek Stein, Lukas T Schroeder, Robert Omage, Katharine Best, Ma Luo, Peter T Hraber, Hanne Andersen-Elyard, Erwing Fabian Cardozo Ojeda, Scott Huang, Dana L Vanlandingham, Stephen Higgs, Alan S Perelson, Jacob D Estes, David Safronetz, Mark G Lewis and James B Whitney in Nature Medicine. Published online October 3 2016 doi:10.1038/nm.4206