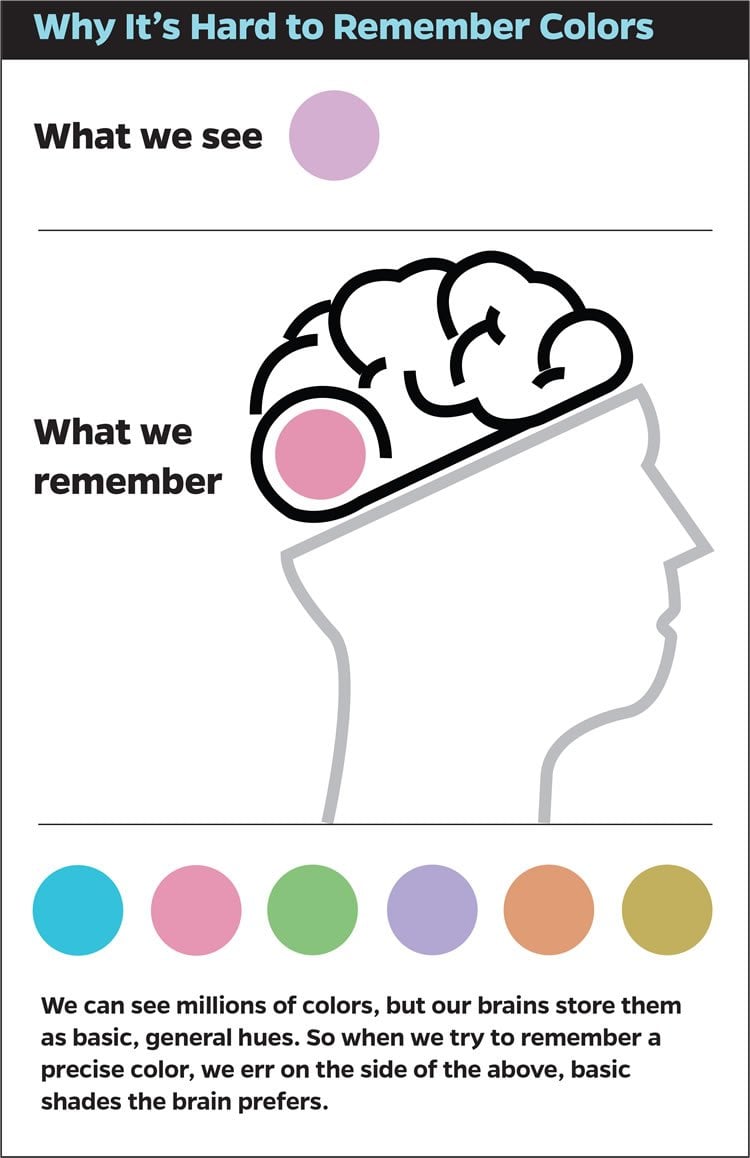

Though people can distinguish between millions of colors, we have trouble remembering specific shades because our brains tend to store what we’ve seen as one of just a few basic hues, a Johns Hopkins University-led team discovered.

In a new paper published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, researchers led by cognitive psychologist Jonathan Flombaum dispute standard assumptions about memory, demonstrating for the first time that people’s memories for colors are biased in favor of “best” versions of basic colors over colors they actually saw.

For example, there’s azure, there’s navy, there’s cobalt and ultramarine. The human brain is sensitive to the differences between these hues —we can, after all, tell them apart. But when storing them in memory, people label all of these various colors as “blue,” the researchers found. The same thing goes for shades of green, pink, purple, etc. This is why, Flombaum said, someone would have trouble glancing at the color of his living room and then trying to match it at the paint store.

“Trying to pick out a color for touch-ups, I’d end up making a mistake,” he said. “This is because I’d mis-remember my wall as more prototypically blue. It could be a green as far as Sherwin-Williams is concerned, but I remember it as blue.”

Flombaum, working with cognitive scientists Gi-Yeul Bae of the University of California, Davis, Maria Olkkonen of the University of Pennsylvania and Sarah R. Allred of Rutgers University, demonstrated that what seems like a difference in the memorability of certain colors is actually the result of the brain’s tendency to categorize colors. People remember colors more accurately, they found, when the colors are good examples of their respective categories.

The team established this color bias and its consequences through a series of experiments. First the researchers asked subjects to look at a color wheel made up of 180 different hues, and to find the “best” examples of blue, pink, green, purple, orange and yellow. Next they conducted a memory experiment with a different group of participants. These participants were shown a colored square for one tenth of a second. They were asked to try to remember it, looking at a blank screen for a little less than one second, and then asked to find the color on the color wheel featuring the 180 hues.

When attempting to match hues, all subjects tended to err on the side of the basic, “best” colors, but the bias toward the archetypes amplified considerably when subjects had to remember the hue, even for less than a second.

“We can differentiate millions of colors, but to store this information, our brain has a trick,” Flombaum said. “We tag the color with a coarse label. That then makes our memories more biased, but still pretty useful.”

The findings have broad implications for the understanding of visual working memory. When faced with a multitude of something — colors, birds, faces — people tend to remember them later as more prototypical, Flombaum said. It’s not that the brain “doesn’t have enough space” to remember the millions of options, he said, it’s that the mind tries to reconcile those precise details with more limited, language-driven categories. So an object that’s teal might be remembered as more “blue” or more “green,” while a coral object might be remembered as more “pink” or more “orange.”

“We have very precise perception of color in the brain, but when we have to pick that color out in the world,” Flombaum said, “there’s a voice that says, “It’s blue,” and that affects what we end up thinking we saw.”

Source: Jill Rosen – Johns Hopkins University

Image Credit: The image is credited to Johns Hopkins University

Original Research: Abstract for “Why Some Colors Appear More Memorable Than Others: A Model Combining Categories and Particulars in Color Working Memory” by Bae, Gi-Yeul; Olkkonen, Maria; Allred, Sarah R.; and Flombaum, Jonathan I. in Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Published online May 18 2015 doi:10.1037/xge0000076

Abstract

Why Some Colors Appear More Memorable Than Others: A Model Combining Categories and Particulars in Color Working Memory

Categorization with basic color terms is an intuitive and universal aspect of color perception. Yet research on visual working memory capacity has largely assumed that only continuous estimates within color space are relevant to memory. As a result, the influence of color categories on working memory remains unknown. We propose a dual content model of color representation in which color matches to objects that are either present (perception) or absent (memory) integrate category representations along with estimates of specific values on a continuous scale (“particulars”). We develop and test the model through 4 experiments. In a first experiment pair, participants reproduce a color target, both with and without a delay, using a recently influential estimation paradigm. In a second experiment pair, we use standard methods in color perception to identify boundary and focal colors in the stimulus set. The main results are that responses drawn from working memory are significantly biased away from category boundaries and toward category centers. Importantly, the same pattern of results is present without a memory delay. The proposed dual content model parsimoniously explains these results, and it should replace prevailing single content models in studies of visual working memory. More broadly, the model and the results demonstrate how the main consequence of visual working memory maintenance is the amplification of category related biases and stimulus-specific variability that originate in perception.

“Why Some Colors Appear More Memorable Than Others: A Model Combining Categories and Particulars in Color Working Memory” by Bae, Gi-Yeul; Olkkonen, Maria; Allred, Sarah R.; and Flombaum, Jonathan I. in Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Published online May 18 2015 doi:10.1037/xge0000076