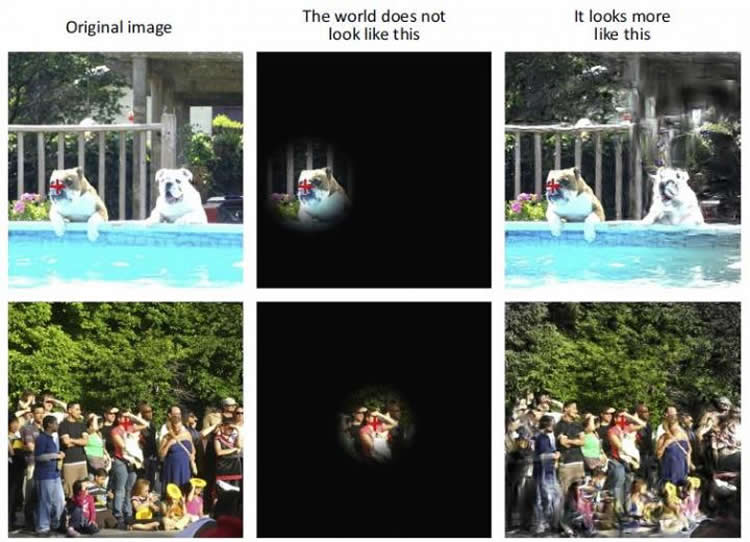

Glance out the window and then close your eyes. What did you see? Maybe you noticed it’s raining and there was a man carrying an umbrella. What color was it? What shape was its handle? Did you catch those details? Probably not. Some neuroscientists would say that, even though you perceived very few specifics from the window scene, your eyes still captured everything in front of you. But there are flaws to this logic, MIT researchers argue in an Opinion published April 19, 2016 in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. It may be that our vision only reflects the gist of what we see.

“A ton of work supports that this perception that our visual experience is so rich and vivid is just totally wrong,” says first author Michael A. Cohen, a postdoctoral fellow in the Nancy Kanwisher Lab at MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research. “But even if we can just see a handful of items, we definitely have an understanding of the world around us — a sense of what kind of scene we’re in.”

A staple study researchers use to quantify our visual consciousness involves showing people flashes of different shapes or objects on a computer screen and asking how many details they can remember. In most cases, subjects report back four or five correct answers. The exception is when subjects are primed to look for something in advance, which changes what they pay attention to. This selective focus is part of why cognitive scientists can’t agree on what we actually “see,” because sight should not be so variable.

For Cohen, however, consciousness is a combination of several processes, including focus and memory, that helps us make decisions about future actions. He points to studies that suggest that our brains are hardwired to quickly take in large objects and scenes (e.g., a highway, a park, a store) within fractions of a second. Glimpse out that window and you take in the depth, navigability, openness, and temperature of the surroundings. The brain does capture some details — for example, you don’t just see a man and an umbrella, but that the man is carrying the umbrella. But most of our visual perception may quite literally be focused on the “big picture.”

“One of the useful things about this field of study is that there are many instances in which your subjective experience is misguided and science can reveal a bunch of things about your own consciousness that you weren’t necessarily aware of,” Cohen says. “There are many experiments in which people are very much surprised by the limits of their own cognitive experiences.”

If we see less than we think that we do, the other senses likely follow similar rules. There’s evidence that audio perception also relies on gists of all of the sounds that we hear. From the window, you take in the sounds of the falling rain, singing birds, and car engines, but what you’re tuning out is the hum of streetlamps or the conversation taking place on the sidewalk. Again, the ears only capture the gist of the environment.

Other researchers will likely disagree with how Cohen and co-authors — Kanwisher and Tufts University cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett — limit consciousness by the bandwidth of memory and decision making. Not to mention that they can’t disprove that we don’t unconsciously “see” all in view.

“It’s very difficult to measure consciousness objectively without conflating reportablity with subjective experience,” Cohen says. “I think this paper gives us hope that we can bridge the gap between what we as scientists can quantify and the subjective impressions that people have when they open their eyes.”

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Joseph Caputo – Cell Press

Image Credit: The image is credited to Cohen et al./Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2016.

Original Research: Full open access research for “What is the Bandwidth of Perceptual Experience?” by Michael A. Cohen, Daniel C. Dennett, and Nancy Kanwisher in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. Published online March 14 2016 doi:/10.1016/j.tics.2016.03.006

Abstract

What is the Bandwidth of Perceptual Experience?

Although our subjective impression is of a richly detailed visual world, numerous empirical results suggest that the amount of visual information observers can perceive and remember at any given moment is limited. How can our subjective impressions be reconciled with these objective observations? Here, we answer this question by arguing that, although we see more than the handful of objects, claimed by prominent models of visual attention and working memory, we still see far less than we think we do. Taken together, we argue that these considerations resolve the apparent conflict between our subjective impressions and empirical data on visual capacity, while also illuminating the nature of the representations underlying perceptual experience.

Trends

Numerous empirical results highlight the limits of visual perception, attention, and working memory. However, it intuitively feels as though we have a rich perceptual experience, leading many to claim that conscious perception overflows these limited cognitive mechanisms.

A relatively new field of study (visual ensembles and summary statistics) provides empirical support for the notion that perception is not limited and that observers have access to information across the entire visual world.

Ensemble statistics, and scene processing in general, also appear to be supported by neural structures that are distinct from those supporting object perception. These distinct mechanisms can work partially in parallel, providing observers with a broad perceptual experience.

Moreover, new demonstrations show that perception is not as rich as is intuitively believed. Thus, ensemble statistics appear to capture the entirety of perceptual experience.

“What is the Bandwidth of Perceptual Experience?” by Michael A. Cohen, Daniel C. Dennett, and Nancy Kanwisher in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. Published online March 14 2016 doi:/10.1016/j.tics.2016.03.006