Summary: According to a new study, boys who show behaviors consistent with psychopathic traits report they did not want to join in with laughter as much as their peers. Additionally, neuroimaging revealed reduced response to the sound of laughter in areas of the brain associated with emotional perception.

Source: Cell Press.

For most people, laughter is highly contagious. It’s nearly impossible to hear or see someone laughing and not feel the urge to join in. But researchers reporting in Current Biology on September 28 have new evidence to show that boys at risk of developing psychopathy when they become adults don’t have that same urge.

Individuals at risk of psychopathy show persistent disruptive behaviors alongside callous-unemotional traits. When asked in the study, boys fitting that description reported that they didn’t want to join in with laughter as much as their peers. Images of their brains also showed reduced response to the sound of laughter. Those differences were seen in brain areas that promote joining in with others and resonating with other people’s emotions, not in auditory brain areas.

“Most studies have focused on how individuals with psychopathic traits process negative emotions and how their lack of response to them might explain their ability to aggress against other people,” says senior author Essi Viding, of University College London. “This prior work is important, but it has not fully addressed why these individuals fail to bond with others. We wanted to investigate how boys at risk of developing psychopathy process emotions that promote social affiliation, such as laughter.”

Viding and colleagues recruited 62 boys aged 11 to 16 with disruptive behaviors with or without callous-unemotional traits and 30 normally behaved, matched controls. The groups were matched on ability, socioeconomic background, ethnicity, and handedness.

“It is not appropriate to label children psychopaths,” Viding explains. “Psychopathy is an adult personality disorder. However, we do know from longitudinal research that there are certain children who are at a higher risk for developing psychopathy, and we screened for those features that indicate that risk.”

The researchers captured the children’s brain activity using functional MRI while they listened to genuine laughter interleaved with posed laughter and crying sounds. The boys who took part were asked, on a scale of 1 to 7, “How much does hearing the sound make you feel like joining in and/or feeling the emotion?” and “How much does the sound reflect a genuinely felt emotion?”

Boys who showed disruptive behavior coupled with high levels of callous-unemotional traits reported less desire to join in with laughter than did normally behaved children or those who were disruptive without showing callous-unemotional traits.

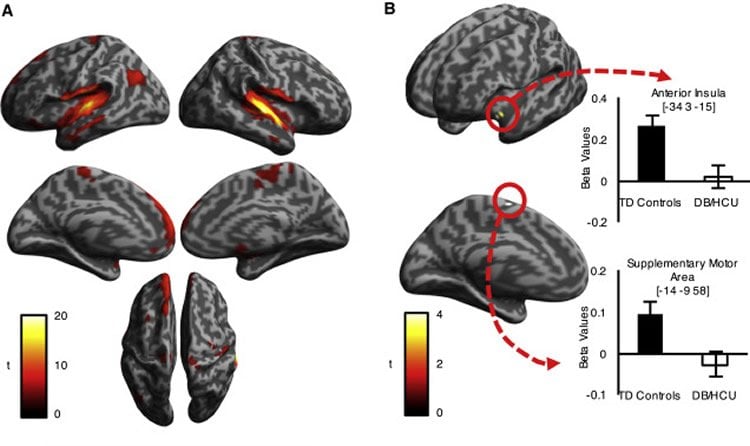

All the boys showed brain activity to genuine laughter in many parts of the brain, including the auditory cortex, where sounds are processed. However, some interesting differences also emerged, and these were particularly pronounced in boys whose disruptive behavior was coupled with callous-unemotional traits. They showed reduced brain activity in the anterior insula and supplementary motor area, brain regions that are thought to facilitate resonating with other people’s emotions and joining in with their laughter. Boys who were disruptive but had low levels of callous-unemotional traits showed some differences too, but not as pronounced as the group with high levels of callous-unemotional traits.

Viding says it’s hard to know whether the reduced response to laughter is a cause or a consequence of the boys’ disruptive behaviors. But the findings should clearly motivate further study into how signals of social affiliation are processed in children at risk of developing psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder. She and her colleagues hope to explore related questions, including whether these children also respond differently to dynamically smiling faces, words of encouragement, or displays of love. They also want to learn at what age those differences arise.

The findings show that kids who are vulnerable to developing psychopathy don’t experience the world quite like the rest of us, Viding says.

“Those social cues that automatically give us pleasure or alert us to someone’s distress do not register in the same way for these children,” she says. “That does not mean that these children are destined to become antisocial or dangerous; rather, these findings shed new light on why they often make different choices from their peers. We are only now beginning to develop an understanding of how the processes underlying prosocial behavior might differ in these children. Such understanding is essential if we are to improve current approaches to treatment for affected children and their families who need our help and support.”

Funding: This work was supported by a UK Medical Research Council grant, a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award, a British Academy Mid-Career Fellowship, and an FCT Investigator Grant from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology.

Source: Joseph Caputo – Cell Press

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Viding et al./Current Biology

Original Research: Full open access research for “Reduced Laughter Contagion in Boys at Risk for Psychopathy” by Elizabeth O’Nions, César F. Lima, Sophie K. Scott, Ruth Roberts, Eamon J. McCrory, and Essi Viding in Current Biology. Published online September 28 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.062

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Cell Press “For Boys At Risk of Psychopathy, Laughter Isn’t So Contagious.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 28 September 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/psychopathy-laughter-boys-7607/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Cell Press (2017, September 28). For Boys At Risk of Psychopathy, Laughter Isn’t So Contagious. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved September 28, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/psychopathy-laughter-boys-7607/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Cell Press “For Boys At Risk of Psychopathy, Laughter Isn’t So Contagious.” https://neurosciencenews.com/psychopathy-laughter-boys-7607/ (accessed September 28, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Reduced Laughter Contagion in Boys at Risk for Psychopathy

Highlights

•Psychopathic traits are associated with a lack of enduring affiliative bonds

•Listening to human laughter engages brain areas that facilitate emotional resonance

•Boys at risk of psychopathy have reduced neural/behavioral responses to laughter

•This could reflect a mechanism underpinning reduced social connectedness

Summary

Humans are intrinsically social animals, forming enduring affiliative bonds. However, a striking minority with psychopathic traits, who present with violent and antisocial behaviors, tend to value other people only insofar as they contribute to their own advancement. Extant research has addressed the neurocognitive processes associated with aggression in such individuals, but we know remarkably little about processes underlying their atypical social affiliation. This is surprising, given the importance of affiliation and bonding in promoting social order and reducing aggression. Human laughter engages brain areas that facilitate social reciprocity and emotional resonance, consistent with its established role in promoting affiliation and social cohesion. We show that, compared with typically developing boys, those at risk for antisocial behavior in general (irrespective of their risk of psychopathy) display reduced neural response to laughter in the supplementary motor area, a premotor region thought to facilitate motor readiness to join in during social behavior. Those at highest risk for developing psychopathy additionally show reduced neural responses to laughter in the anterior insula. This region is implicated in auditory-motor processing and in linking action tendencies with emotional experience and subjective feelings. Furthermore, this same group reports reduced desire to join in with the laughter of others—a behavioral profile in part accounted for by the attenuated anterior insula response. These findings suggest that atypical processing of laughter could represent a novel mechanism that impoverishes social relationships and increases risk for psychopathy and antisocial behavior.

“Reduced Laughter Contagion in Boys at Risk for Psychopathy” by Elizabeth O’Nions, César F. Lima, Sophie K. Scott, Ruth Roberts, Eamon J. McCrory, and Essi Viding in Current Biology. Published online September 28 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.062