Each of us has, in our nose, about six million smell receptors of around four hundred different types. The distribution of these receptors varies from person to person – so much so that each person’s sense of smell may be unique. In research recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Weizmann Institute scientists report on a method of precisely characterizing an individual’s sense of smell, which they call an “olfactory fingerprint.”

The implications of this study reach beyond the sense of smell alone, and range from olfactory fingerprint-based early diagnosis of degenerative brain disorders to a non-invasive test for matching donor organs.

The method is based on how similar or different two odors are from one another. In the first stage of the experiment, volunteers were asked to rate 28 different smells according to 54 different descriptive words, for example, “lemony,” or “masculine.” The experiment, led by Dr. Lavi Secundo, together with Dr. Kobi Snitz and Kineret Weissler, all members of the lab of Prof. Noam Sobel of the Weizmann Institute’s Neurobiology Department, developed a complex, multidimensional mathematical formula for determining, based on the subjects’ ratings, how similar any two odors are to one another in the human sense of smell. The strength of this formula, according to Secundo, is that it does not require the subjects to agree on the use and applicability of any given verbal descriptor. Thus, the fingerprint is odor dependent but descriptor and language independent.

The 28 odors make for 378 different pairs, each with a different level of similarity. This provides us with a 378-dimensional fingerprint. Using this highly sensitive tool, the scientists found that each person indeed has an individual unique pattern – an olfactory fingerprint.

Could this finding extend to millions of people? The researchers say their computations show that 28 odors alone could be used to “fingerprint” some two million people, and just 34 odors would be enough to identify any of the seven billion individuals on the planet.

The next stage of the research suggested that our olfactory fingerprint may tie in with another system of ours in which we all differ – the immune system. They found, for example, that an immune antigen called HLA, today used to assess matches for organ donation, is correlated with certain olfactory fingerprints. This part of the study was conducted together with Drs. Ron Loewenthal, and Nancy Agmon-Levin, and Prof. Yehuda Shoenfeld, all of Sheba Medical Center.

The researchers think that olfactory fingerprinting, in addition to helping identify individuals, could be developed into methods for the early detection of such diseases as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, and it could lead to non-invasive methods of initial screening as to whether bone marrow or organs from live donors are a good match.

Funding: Prof. Noam Sobel’s research is supported by the Norman and Helen Asher Center for Brain Imaging, which he heads; the Nella and Leon Benoziyo Center for Neurosciences, which he heads; the Carl and Micaela Einhorn-Dominic Institute for Brain Research, which he heads; the Nadia Jaglom Laboratory for the Research in the Neurobiology of Olfaction; the Adelis Foundation; the James S. McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Scholar in Understanding Human Cognition Program; Mr. & Mrs. H. Thomas Beck, Canada; the Minerva Foundation; the European Research Council; Nathan and Dora Oks, France; Mike and Valeria Rosenbloom through the Mike Rosenbloom Foundation; and the Estate of David Levidow.

Source: Yael Edelman – Weizmann Institute of Science

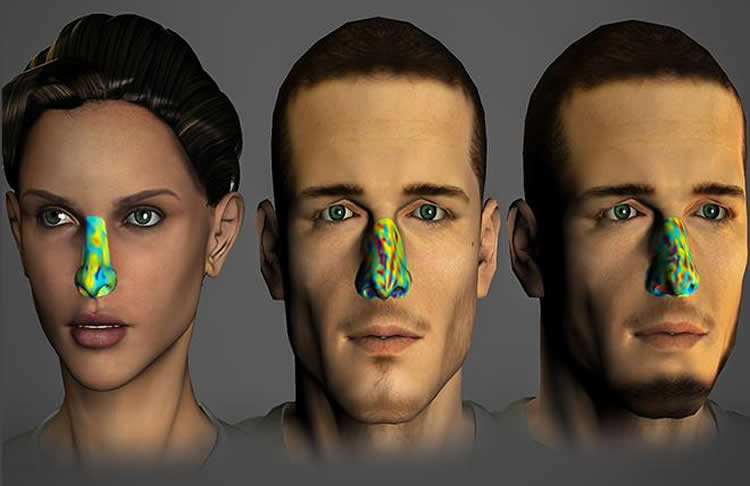

Image Credit: Image is credited to Weizmann Institute of Science

Original Research: Abstract for “Individual olfactory perception reveals meaningful nonolfactory genetic information” by Lavi Secundo, Kobi Snitz, Kineret Weissler, Liron Pinchover, Yehuda Shoenfeld, Ron Loewenthal, Nancy Agmon-Levin, Idan Frumin, Dana Bar-Zvi, Sagit Shushan, and Noam Sobel in PNAS. Published online June 22 2015 doi:10.1073/pnas.1424826112

Abstract

Individual olfactory perception reveals meaningful nonolfactory genetic information

Each person expresses a potentially unique subset of ∼400 different olfactory receptor subtypes. Given that the receptors we express partially determine the odors we smell, it follows that each person may have a unique nose; to capture this, we devised a sensitive test of olfactory perception we termed the “olfactory fingerprint.” Olfactory fingerprints relied on matrices of perceived odorant similarity derived from descriptors applied to the odorants. We initially fingerprinted 89 individuals using 28 odors and 54 descriptors. We found that each person had a unique olfactory fingerprint (P < 10−10), which was odor specific but descriptor independent. We could identify individuals from this pool using randomly selected sets of 7 odors and 11 descriptors alone. Extrapolating from this data, we determined that using 34 odors and 35 descriptors we could individually identify each of the 7 billion people on earth. Olfactory perception, however, fluctuates over time, calling into question our proposed perceptual readout of presumably stable genetic makeup. To test whether fingerprints remain informative despite this temporal fluctuation, building on the linkage between olfactory receptors and HLA, we hypothesized that olfactory perception may relate to HLA. We obtained olfactory fingerprints and HLA typing for 130 individuals, and found that olfactory fingerprint matching using only four odorants was significantly related to HLA matching (P < 10−4), such that olfactory fingerprints can save 32% of HLA tests in a population screen (P < 10−6). In conclusion, a precise measure of olfactory perception reveals meaningful nonolfactory genetic information. "Individual olfactory perception reveals meaningful nonolfactory genetic information" by Lavi Secundo, Kobi Snitz, Kineret Weissler, Liron Pinchover, Yehuda Shoenfeld, Ron Loewenthal, Nancy Agmon-Levin, Idan Frumin, Dana Bar-Zvi, Sagit Shushan, and Noam Sobel in PNAS. Published online June 22 2015 doi:10.1073/pnas.1424826112