Summary: In as little as two years of learning, music can change the structure of the brain’s white matter and boost networks implicated in decision making in children, USC researchers report.

Source: USC.

If the brain is a muscle, then learning to play an instrument and read music is the ultimate exercise.

Two new studies from the Brain and Creativity Institute at USC show that as little as two years of music instruction has multiple benefits. Music training can change both the structure of the brain’s white matter, which carries signals through the brain, and gray matter, which contains most of the brain’s neurons that are active in processing information. Music instruction also boosts engagement of brain networks that are responsible for decision-making and the ability to focus attention and inhibit impulses.

The benefits were revealed in studies published recently in scientific journals, including one in the journal Cerebral Cortex.

The results are from an ongoing longitudinal study that began in 2012, when the institute, based at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, established a partnership with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Association and Heart of Los Angeles (HOLA) to examine the impact of music instruction on children’s social, emotional and cognitive development.

The neuroscientists have been monitoring the brain development and behavior of children from underserved neighborhoods in Los Angeles, including some learning to play music with the Youth Orchestra Los Angeles at HOLA.

To examine the impact of music training on their brains, the scientists have used several scientific techniques, including behavioral testing, structural and functional MRI scans, and EEG to track electrical activity in the brains.

Initial results published last year showed that music training accelerates maturity in areas of the brain responsible for sound processing, language development, speech perception and reading skills.

“Together these results demonstrate that community music programs can offset some of the negative consequences that low socioeconomic status can have on child development,” said Assal Habibi, the lead author and an assistant research professor of psychology.

A growing body of research has shown that poverty can greatly disrupt or hinder brain development for children, affecting their performance in school.

A developmental crescendo

For the latest studies, the neuroscientists tracked and monitored changes in 20 children who had started learning to play and read music through the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Youth Orchestra Los Angeles program at HOLA at age 6 or 7. The community music training program resembles one that Los Angeles Philharmonic music and artistic director Gustavo Dudamel had been in when he was growing up in Venezuela, where it was known as El Sistema.

The Youth Orchestra Los Angeles students in this study learned to play instruments, such as the violin, in ensembles and groups, and they practice up to seven hours a week.

The scientists also compared the musicians to peers in two other groups: 19 children in a community sports program, and, as a control group, 21 children who were not involved in any specific after-school programs.

Sounding off

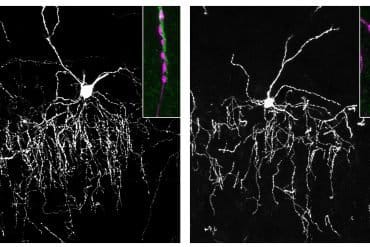

In the Brain and Creativity Institute study, children receiving music instruction, compared to peers, demonstrated changes in thickness and volume of brain regions that are engaged in processing sound.

These regions, called “auditory association areas,” are located just above the ears. Cortical thickness is a reliable measure of brain maturity. Children who have received music training showed differences in the thickness of the auditory areas in the right versus the left hemisphere, a sign that music training impacts brain structure. In addition, children learning to play and read music showed a stronger robustness of the white matter, a sign of stronger connectivity in the corpus callosum, an area that allows communication between the two hemispheres of the brain.

“There has been a long suspicion that music practice has a beneficial effect on human behavior. But this study proves convincingly that the effect is real,” said Antonio Damasio, University Professor and director of the Brain and Creativity Institute.

In a study published two weeks ago in the journal PLoS One, the neuroscientists at the institute found that when the young musicians were performing an intellectual task, they demonstrated greater engagement of a brain network that is involved in executive function and decision-making.

For the task, known in psychology research as the “color-word Stroop task,” children were presented with a word whose meaning at times matched its color.

For example, the word “blue” appeared in blue font. In some instances, however, there was an incongruency, such as the word blue appearing in a red font. To test their impulse control and decision-making abilities, children were asked to ignore the written words and instead name the color of the word. Children completed the task while undergoing an MRI scan, which tracked the differences in brain responses between children learning music and those who were not.

“We have documented longitudinal changes in the brains of the children receiving music instruction that are distinct from the typical brain changes that children that age would develop,” Habibi said. “Our findings suggest that musical training is a powerful intervention that could help children mature emotionally and intellectually.”

BCI co-directors Antonio Damasio and Hanna Damasio were co-authors of the Cerebral Cortex study along with BCI research associate Ryan Veiga; Beatriz Ilari of the USC Thornton School of Music; and Anand Joshi, Justin Haldar and Richard Leahy of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering.

Co-authors of the PLOS One study published on Oct. 30 included Jonas Kaplan, graduate student Matthew Sachs and Alissa Der Sarkissian, a research assistant at BCI.

Funding: The study was supported by the Brain and Creativity Institute Research Fund.

Source: Emily Ortman – USC

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Craig T. Mathew, Mathew Imaging.

Original Research: The first study will appear in Cerebral Cortex.

Full open access research for “Increased engagement of the cognitive control network associated with music training in children during an fMRI Stroop task” by Matthew Sachs, Jonas Kaplan, Alissa Der Sarkissian, and Assal Habibi in PLOS ONE. Published online October 30 2017 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187254

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]USC “Music Training Changes Children’s Brain Structure and Boosts Decision Making Network.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 14 November 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/kids-music-brain-structure-7941/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]USC (2017, November 14). Music Training Changes Children’s Brain Structure and Boosts Decision Making Network. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved November 14, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/kids-music-brain-structure-7941/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]USC “Music Training Changes Children’s Brain Structure and Boosts Decision Making Network.” https://neurosciencenews.com/kids-music-brain-structure-7941/ (accessed November 14, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Increased engagement of the cognitive control network associated with music training in children during an fMRI Stroop task

Playing a musical instrument engages various sensorimotor processes and draws on cognitive capacities collectively termed executive functions. However, while music training is believed to associated with enhancements in certain cognitive and language abilities, studies that have explored the specific relationship between music and executive function have yielded conflicting results. As part of an ongoing longitudinal study, we investigated the effects of music training on executive function using fMRI and several behavioral tasks, including the Color-Word Stroop task. Children involved in ongoing music training (N = 14, mean age = 8.67) were compared with two groups of comparable general cognitive abilities and socioeconomic status, one involved in sports (“sports” group, N = 13, mean age = 8.85) and another not involved in music or sports (“control” group, N = 17, mean age = 9.05). During the Color-Word Stroop task, children with music training showed significantly greater bilateral activation in the pre-SMA/SMA, ACC, IFG, and insula in trials that required cognitive control compared to the control group, despite no differences in performance on behavioral measures of executive function. No significant differences in brain activation or in task performance were found between the music and sports groups. The results suggest that systematic extracurricular training, particularly music-based training, is associated with changes in the cognitive control network in the brain even in the absence of changes in behavioral performance.

“Increased engagement of the cognitive control network associated with music training in children during an fMRI Stroop task” by Matthew Sachs, Jonas Kaplan, Alissa Der Sarkissian, and Assal Habibi in PLOS ONE. Published online October 30 2017 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187254