Summary: Researchers from Duke University report people with poor sleep quality were less likely to experience symptoms of depression if they had higher activity in the ventral striatum.

Source: Duke University.

Poor sleep is both a risk factor, and a common symptom, of depression. But not everyone who tosses and turns at night becomes depressed.

Individuals whose brains are more attuned to rewards may be protected from the negative mental health effects of poor sleep, says a new study by Duke University neuroscientists.

The researchers found that college students with poor quality sleep were less likely to have symptoms of depression if they also had higher activity in a reward-sensitive region of the brain.

“This helps us begin to understand why some people are more likely to experience depression when they have problems with sleep,” said Ahmad Hariri, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. “This finding may one day help us identify individuals for whom sleep hygiene may be more effective or more important.”

The paper appeared online Sept. 18 in The Journal of Neuroscience.

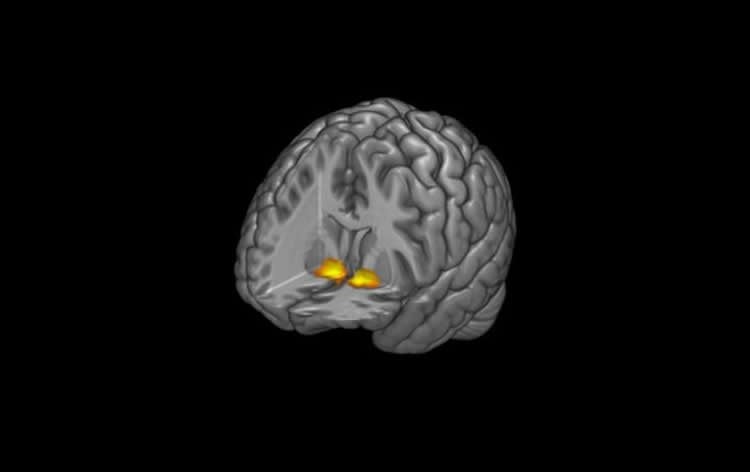

The researchers examined a region deep within the brain called the ventral striatum (VS), which helps us regulate behavior in response to external feedback. The VS helps reinforce behaviors that are rewarded, while reducing behaviors that are not.

Electrical stimulation of the VS has been shown to reduce symptoms of depression in patients who are resistant to other forms of treatment, and earlier studies by Hariri’s team show that people with higher reward-related VS activity are more resilient to stress.

“We’ve shown that reward-related VS activity may act as a buffer against the negative effects of stress on depressive symptoms,” said Reut Avinun, a postdoctoral researcher in Hariri’s group at Duke and the lead author of the study. “I was interested in examining whether the same moderating effect would also be seen if we look at sleep disturbances.”

Avinun examined the brain activity of 1,129 college students participating in the Duke Neurogenetics Study. Each participant completed a series of questionnaires to evaluate sleep quality and depressive symptoms, and also completed an fMRI scan while engaging in a task that activates the VS.

In the task, students were shown the back of a computer-generated card and asked to guess whether the value of the card was greater than or less than five. After they guessed, they received feedback on whether they were right or wrong. But the game was rigged, so that during different trials the students were either right 80 percent of the time or wrong 80 percent of the time.

To tease out whether general feedback, or specifically reward-related feedback, buffers against depression, the researchers compared VS brain activity during trials when the students were mostly right to those when they were mostly wrong but still received feedback.

They found that those who were less susceptible to the effects of poor sleep showed significantly higher VS activity in response to positive feedback or reward compared to negative feedback.

“Rather than being more or less responsive to the consequences of any actions, we are able to more confidently say it is really the response to positive feedback, to doing something right, that seems to be part of this pattern,” Hariri said.

“It is almost like this reward system gives you a deeper reserve,” Hariri said. “Poor sleep is not good, but you may have other experiences during your life that are positive. And the more responsive you are to those positive experiences, the less vulnerable you may be to the depressive effects of poor sleep.”

Funding: This research was supported by Duke University and grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DA033369, R01DA031579 and R01AG049789) and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (NSF DGE- 1644868).

Source: Kara Manke – Duke University

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Annchen R. Knodt, Duke University.

Original Research: Abstract for “Reward-Related Ventral Striatum Activity Buffers Against the Experience of Depressive Symptoms Associated with Sleep Disturbances” by Reut Avinun, Adam Nevo, Annchen R. Knodt, Maxwell L. Elliott, Spenser R. Radtke, Bartholomew D. Brigidi and Ahmad R. Hariri in Journal of Neuroscience. Published online September 18 2017 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1734-17.2017

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Duke University “Why Bad Sleep Doesn’t Always Lead to Depression.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 18 September 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/depression-sleep-7511/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Duke University (2017, September 18). Why Bad Sleep Doesn’t Always Lead to Depression. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved September 18, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/depression-sleep-7511/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Duke University “Why Bad Sleep Doesn’t Always Lead to Depression.” https://neurosciencenews.com/depression-sleep-7511/ (accessed September 18, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Reward-Related Ventral Striatum Activity Buffers Against the Experience of Depressive Symptoms Associated with Sleep Disturbances

Sleep disturbances represent one risk factor for depression. Reward-related brain function, particularly the activity of the ventral striatum (VS), has been identified as a potential buffer against stress-related depression. We were therefore interested in testing whether reward-related VS activity would moderate the effect of sleep disturbances on depression in a large cohort of young adults. Data were available from 1129 university students (mean age 19.71 ± 1.25 years; 637 women) who completed a reward-related functional MRI task to assay VS activity and provided self-reports of sleep using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and symptoms of depression using a summation of the General Distress/Depression (GDD) and Anhedonic Depression (AD) subscales of the Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire-short form. Analyses revealed that as VS activity increased the association between sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms decreased. The interaction between sleep disturbances and VS activity was robust to the inclusion of sex, age, race/ethnicity, past or present clinical disorder, early or recent life stress, and anxiety symptoms, as well as the interactions between VS activity and early or recent life stress as covariates. We provide initial evidence that high reward-related VS activity may buffer against depressive symptoms associated with poor sleep. Our analyses help advance an emerging literature supporting the importance of individual differences in reward-related brain function as a potential biomarker of relative risk for depression.

Significance Statement: Sleep disturbances are a common risk factor for depression. An emerging literature suggests that reward-related activity of the ventral striatum (VS), a brain region critical for motivation and goal-directed behavior, may buffer against the effect of negative experiences on the development of depression. Using data from a large sample of 1129 university students we demonstrate that as reward-related VS activity increases, the link between sleep disturbances and depression decreases. This finding contributes to accumulating research demonstrating that reward-related brain function may be a useful biomarker of relative risk for depression in the context of negative experiences.

“Reward-Related Ventral Striatum Activity Buffers Against the Experience of Depressive Symptoms Associated with Sleep Disturbances” by Reut Avinun, Adam Nevo, Annchen R. Knodt, Maxwell L. Elliott, Spenser R. Radtke, Bartholomew D. Brigidi and Ahmad R. Hariri in Journal of Neuroscience. Published online September 18 2017 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1734-17.2017