Scientists have found a signal in the brain that reflects young children’s aversion to members of the opposite sex (the “cooties” effect) and also their growing interest in opposite-sex peers as they enter puberty. These two responses to members of the opposite sex are encoded in the amygdala, the researchers report.

The findings, reported in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, challenge traditional notions about the role of the amygdala, the researchers say.

The team evaluated 93 children’s attitudes toward same-sex and opposite-sex peers. Using functional MRI, which tracks how oxygenated blood flows in the brain, the researchers also analyzed brain activity in 52 children.

The amygdala was once thought of as a “threat detector,” said University of Illinois psychology and Beckman Institute professor Eva Telzer, who led the new analysis. “But increasing evidence indicates that it is activated whenever someone detects something meaningful in the environment,” she said. “It is a significance detector.”

The finding that very young children are paying close attention to gender is not a surprise, Telzer said.

“We know that there are developmental changes in terms of the significance of gender boundaries in young kids,” Telzer said. “We also know about the whole ‘cooties’ phenomenon,” where young children develop an aversion to opposite-sex peers and act as if members of the opposite sex could, if they got too close, contaminate them with a dreadful infestation. Children at this age also tend to strongly prefer the company of their same-sex peers, she said.

This phenomenon was reflected in young children’s evaluations of each other.

“Only the youngest children in our sample demonstrated a behavioral sex bias such that they rated same-sex peers as having more positive (and less negative) attributes than opposite-sex peers,” the researchers wrote.

“And so we think the amygdala is signaling the significance of cooties at this developmental period,” Telzer said.

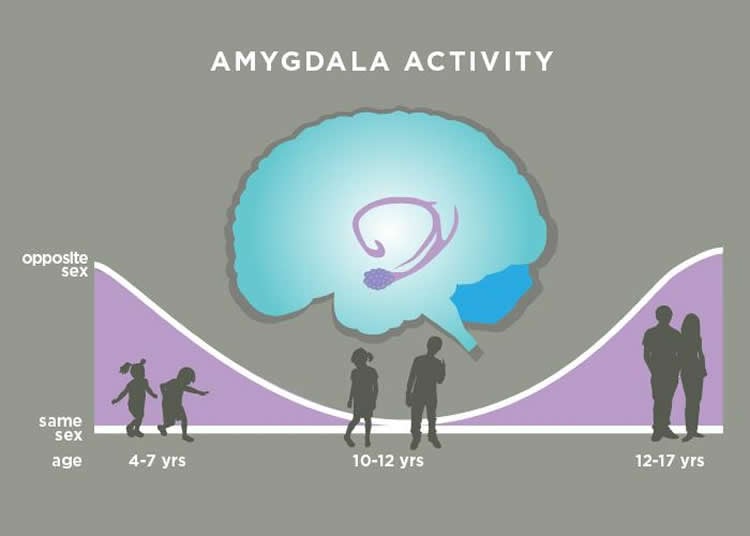

The interest in opposite-sex peers tends to wane in later childhood, just before puberty, Telzer said. The researchers saw no difference in the amygdala’s response to same-sex and opposite-sex faces in children between the ages of 10 and 12. (See graphic.)

But in puberty, children’s interest in opposite-sex peers blooms anew. They may become infatuated with a member of the opposite sex, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as a “crush,” Telzer said.

“When puberty hits, gender becomes more significant again, whether it’s because your body is changing, or because of sexual attraction or you are becoming aware of more rigid sexual boundaries as you become more sexually mature,” Telzer said. “The brain is responding very appropriately, in terms of what’s changing developmentally.”

Funding: The National Institute of Mental Health at the National Institutes of Health supported this research.

Written by Diana Yates

Source: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign press release

Image Source: The image is credited to Julie McMahon

Original Research: Abstract for “The Cooties Effect”: Amygdala Reactivity to Opposite- versus Same-sex Faces Declines from Childhood to Adolescence” by Eva H. Telzer, Jessica Flannery, Kathryn L. Humphreys, Bonnie Goff, Laurel Gabard-Durman, Dylan G. Gee, and Nim Tottenham in Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. Published online April 7 2015 doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00813

Abstract

“The Cooties Effect”: Amygdala Reactivity to Opposite- versus Same-sex Faces Declines from Childhood to Adolescence

One of the most important social identities that children learn to define themselves and others by is sex, becoming a salient social category by early childhood. Although older children begin to show greater flexibility in their gendered behaviors and attitudes, gender rigidity intensifies again around the time of puberty. In the current study, we assessed behavioral and neural biases to sex across a wide age group. Ninety-three youth (ages 7–17 years) provided behavioral rating of same- and opposite-sex attitudes, and 52 youth (ages 4–18 years) underwent an fMRI scan as they matched the emotion of same- and opposite-sex faces. We demonstrate significant age-related behavioral biases of sex that are mediated by differential amygdala response to opposite-sex relative to same-sex faces in children, an effect that completely attenuates by the teenage years. Moreover, we find a second peak in amygdala sensitivity to opposite-sex faces around the time of puberty. Thus, the amygdala codes for developmentally dependent and motivationally relevant social identification across development.

“The Cooties Effect”: Amygdala Reactivity to Opposite- versus Same-sex Faces Declines from Childhood to Adolescence” by Eva H. Telzer, Jessica Flannery, Kathryn L. Humphreys, Bonnie Goff, Laurel Gabard-Durman, Dylan G. Gee, and Nim Tottenham in Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. Published online April 7 2015 doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00813