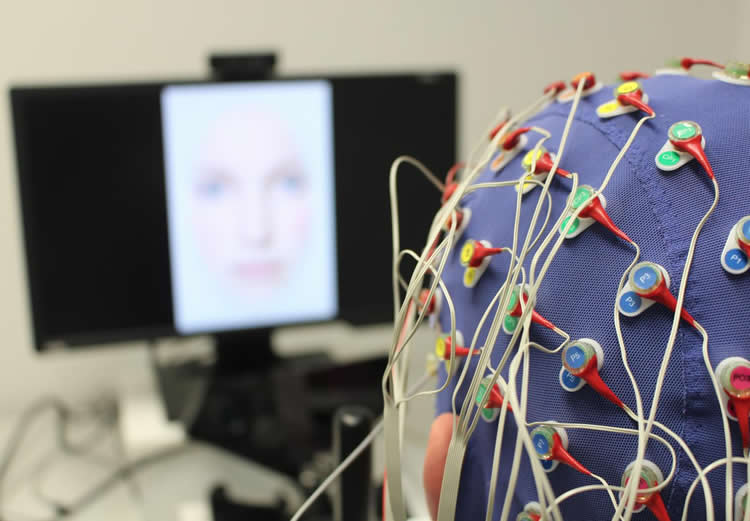

Summary: Researchers used EEG to investigate how the brain processes stimuli to determine whether an image or word is positive or negative. The study found words associated with loss causes neural reactions in the visual cortex after 100 milliseconds.

Source: University of Gottigen.

Many objects and people in everyday life have an emotional meaning. A pair of wool socks, for example, has an emotional value if it was the last thing the grandmother knitted before her death. The same applies to words. The name of a stranger has no emotional value at first, but if a loving relationship develops, the same name suddenly has a positive connotation. Researchers at the University of Göttingen have investigated how the brain processes such stimuli, which can be positive or negative. The results were published in the journal Neuropsychologia.

The scientists from the Georg Elias Müller Institute for Psychology at the University of Göttingen analysed how people associate neutral signs, words and faces with emotional meaning. Within just a few hours, participants learn these connections through a process of systematic rewards and losses. For example, if they always receive money when they see a certain neutral word, this word acquires a positive association. However, if they lose money whenever they see a certain word, this leads to a negative association. The studies show that people learn positive associations much faster than neutral or negative associations: something positive very quickly becomes associated with a word or indeed with the face of a person (as their recent research in Neuroimage has shown).

Using electroencephalography (EEG), the researchers also investigated how the brain processes the various stimuli. The brain usually determines whether an image or word is positive or negative after about 200 to 300 milliseconds. “Words associated with loss cause specific neuronal reactions in the visual cortex after just 100 milliseconds,” says Dr Louisa Kulke, first author of the study. “So the brain distinguishes in a flash what a newly learned meaning the word has for us, especially if that meaning is negative.”

It also seems to make a difference whether the word is already known to the subject (like “chair” or “tree”) or whether it is a fictitious word that does not exist in the language (like “napo” or “foti”). Thus, the existing semantic meaning of a word seems to play a role in the emotions that we associate with that word.

Source: Melissa Sollich – University of Gottigen

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Anap-Lab.

Original Research: Abstract for “Differential effects of learned associations with words and pseudowords on event-related brain potentials” by Louisa Kulke, Mareike Bayer, Anna-Maria Grimm,and Annekathrin Schacht in Neuropsychologia. Published December 17 2018.

doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.12.012

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]University of Gottigen”How Words Get an Emotional Meaning.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 9 January 2019.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/words-emotion-meaning-10474/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]University of Gottigen(2019, January 9). How Words Get an Emotional Meaning. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved January 9, 2019 from https://neurosciencenews.com/words-emotion-meaning-10474/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]University of Gottigen”How Words Get an Emotional Meaning.” https://neurosciencenews.com/words-emotion-meaning-10474/ (accessed January 9, 2019).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Differential effects of learned associations with words and pseudowords on event-related brain potentials

Associated stimulus valence affects neural responses at an early processing stage. However, in the field of written language processing, it is unclear whether semantics of a word or low-level visual features affect early neural processing advantages. The current study aimed to investigate the role of semantic content on reward and loss associations. Participants completed a learning session to associate either words (Experiment 1, N = 24) or pseudowords (Experiment 2, N = 24) with different monetary outcomes (gain-associated, neutral or loss-associated). Gain-associated stimuli were learned fastest. Behavioural and neural response changes based on the associated outcome were further investigated in separate test sessions. Responses were faster towards gain- and loss-associated than neutral stimuli if they were words, but not pseudowords. Early P1 effects of associated outcome occurred for both pseudowords and words. Specifically, loss-association resulted in increased P1 amplitudes to pseudowords, compared to decreased amplitudes to words. Although visual features are likely to explain P1 effects for pseudowords, the inversed effect for words suggests that semantic content affects associative learning, potentially leading to stronger associations.