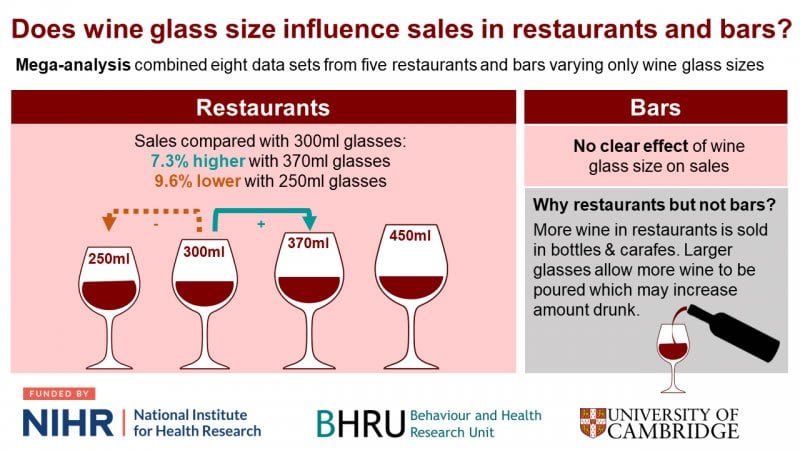

Summary: Restaurants serving wine in 370ml glasses, rather than 300ml glasses, sold more wine. However, they tended to sell less when 250ml glasses were used. The same effect was not seen in bars.

Source: University of Cambridge

The size of glass used for serving wine can influence the amount of wine drunk, suggests new research from the University of Cambridge, funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR). The study found that when restaurants served wine in 370ml rather than 300ml glasses they sold more wine, and tended to sell less when they used 250ml glasses. These effects were not seen in bars.

Alcohol is the fifth largest contributor to early death in high income countries and the seventh world-wide. One proposed way of reducing the amount of alcohol consumed is to reduce the size of wine glasses, though until now the evidence supporting such a move has been inconclusive and often contradictory.

Wine glasses have increased in size almost seven-fold over the last 300 years with the most marked increase being a doubling in size since 1990. Over the past three centuries, the amount of wine consumed in England has more than quadrupled, although the number of wine consumers stayed constant. Wine sales in bars and restaurants are either of fixed serving sizes when sold by the glass, or – particularly in restaurants – sold by the bottle or carafe for free-pouring by customers or staff.

A preliminary study carried out by researchers at the Behaviour and Health Research Unit, University of Cambridge, suggested that serving wine in larger wine glasses – while keeping the measure the same – led to a significant increase in the amount of wine sold.

To provide a robust estimate of the effect size of wine glass size on sales – a proxy for consumption – the Cambridge team did a ‘mega-analysis’ that brought together all of their previously published datasets from studies carried out between 2015 and 2018 at bars and restaurants in Cambridge. The team used 300ml glasses as the reference level against which to compare differences in consumption.

In restaurants, when glass size was increased to 370ml, wine sales increased by 7.3%. Reducing the glass size to 250ml led to a drop of 9.6%, although confidence intervals (the range of values within which the researchers can be fairly certain their true value lies) make this figure uncertain. Curiously, increasing the glass size further to 450ml made no difference compared to using 300ml glasses.

“Pouring wine from a bottle or a carafe, as happens for most wine sold in restaurants, allows people to pour more than a standard serving size, and this effect may increase with the size of the glass and the bottle,” explained first author Dr Mark Pilling. “If these larger portions are still perceived to be ‘a glass’, then we would expect people to buy and consume more wine with larger glasses.

“As glass sizes of 300ml and 370ml are commonly used in restaurants and bars, drinkers may not have noticed the difference and still assumed they were pouring a standard serving. When smaller glass sizes of 250ml are available, they may also appear similar to 300ml glasses but result in a smaller amount of wine being poured. In contrast, very large glasses, such as the 450ml glasses, are more obviously larger, so drinkers may have taken conscious measures to reduce how much they drink, such as drinking more slowly or pouring with greater caution.”

The researchers also found similar internal patterns to those reported in previous studies, namely lower sales of wine on warmer days and much higher sales on Fridays and Saturdays than on Mondays.

The researchers found no significant differences in wine sales by glass size in bars – in contrast to the team’s earlier study. This shows the importance of replicating research to increase our ability to detect the effects of wine glass size. When combined with data from other experiments, the apparent effect in bars disappeared.

“If we are serious about tackling the negative effects of drinking alcohol, then we will need to understand the factors that influence how much we consume,” added senior author Professor Dame Theresa Marteau. “Given our findings, regulating wine glass size is one option that might be considered for inclusion in local licensing regulations for reducing drinking outside the home.”

Professor Ashley Adamson, Director of the NIHR School of Public Health Research, said: “We all like to think we’re immune to subtle influences on our behaviour – like the size of a wine glass – but research like this clearly shows we’re not.

“This important work helps us understand how the small, everyday details of our lives affect our behaviours and so our health. Evidence like this can shape policies that would make it easier for everyone to be a bit healthier without even having to think about it.”

Clive Henn, Senior Alcohol Advisor at Public Health England, welcomed the report: “This interesting study suggests a new alcohol policy approach by looking at how the size of wine glasses may influence how much we drink. It shows how our drinking environment can impact on the way we drink and help us to understand how to develop a drinking environment which helps us to drink less.”

Funding: The study received additional funding from Wellcome.

Source:

University of Cambridge

Media Contacts:

Craig Brierley – University of Cambridge

Image Source:

The image is credited to NIHR/University of Cambridge/BHRU.

Original Research: Open access

“The effect of wine glass size on volume of wine sold: A mega-analysis of studies in bars and restaurants”. Pilling, M, Clarke N, Pechey R, Hollands GJ, Marteau TM.

Addiction doi:110.1111/add.14998.

Abstract

The effect of wine glass size on volume of wine sold: A mega-analysis of studies in bars and restaurantsn

Aim

To estimate the effects of wine glass size on volume of wine sold in bars and restaurants.

Design

A mega‐analysis combining raw (as opposed to aggregate‐level) data from eight studies conducted in five establishments. A multiple treatment reversal design was used for each data set, with wine glass size changed fortnightly while serving sizes were unaffected, in studies lasting between 14 and 26 weeks.

Setting and participants

Five bars and restaurants in England participated in studies between 2015 and 2018, using wine glasses of five sizes: 250, 300, 370, 450 and 510 ml, with the largest size only used in bars.

Measurements

Daily volume of wine sold by the glass, bottle or carafe for non‐sparkling wine were recorded at bars (594 days) and restaurants (427 days), averaging 4 months per study.

Findings

Mega‐analysis combining data from bars did not find a significant effect of glass size on volume of wine sold compared with 300‐ml glasses: the volume of wine sold using 370‐ml glasses was 0.5% lower [95% confidence interval (CI) = –8.1% to 6.1%], using 450‐ml glasses was 1.0% higher (95% CI = –9.1 to 12.2) and using 510‐ml glasses was 0.4% lower (95% CI = –9.4 to 9.4). For restaurants, compared with 300‐ml glasses, the volume of wine sold using 250‐ml glasses did not show a significant difference: 9.6% lower (95% CI = –19.0 to 0.7). Using 370‐ml glasses the volume of wine sold was 7.3% higher (95% CI = 1.5% to 13.5%); no significant effect was found using 450‐ml glasses: 0.9% higher (95% CI = –5.5 to 7.7).

Conclusions

The volume of wine sold in restaurants in England may be greater when 370‐ml glasses are used compared with 300‐ml wine glasses, but may not be in bars. This might be related to restaurants compared with bars selling more wine in bottles and carafes, which require free‐pouring.