Potential new drug target identified for treating short-term itch.

No matter the trigger — bug bites, a medication side-effect or an itchy wound — the urge to scratch can be a real pain. Researchers at the Duke University Medical Center have identified a potential drug target in the skin for that itchy feeling.

Published early online in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, their study also shows that skin can go beyond its known role as a protective barrier. When cells from outer layers of skin are exposed to certain itch-producing chemicals, they function to powerfully regulate sensory nerve cells, telling them to pass the feeling of itch along to the brain.

“This study is exciting for basic science but also from the translational-medical side. It means that [short-term] itch is something we can rationally treat,” said the study’s senior investigator Wolfgang Liedtke, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of neurology, anesthesiology and neurobiology at Duke University School of Medicine, who as a physician treats patients with head and face pain and also associated itch. “We can now envision developing topical treatments for the skin that target specific molecular pathways to suppress itch and inflammation.”

In a 2013 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Liedtke and his collaborators showed that an ion channel protein abundant in skin cells called TRPV4 was crucial for conveying feelings of pain caused by over-exposure to ultraviolet-B radiation, such as in sunburn.

In that study, the team found that ultraviolet-B switched on TRPV4, which then caused skin cells to release a molecule called endothelin-1. Endothelin-1 has been implicated in both pain and itch sensations. But the scientists wondered whether TRPV4 was also involved in itch.

In the new study, Liedtke’s team used genetically engineered mice in which they dialed down TRPV4 selectively in the animals’ skin cells and then exposed them to a handful of itch-causing chemicals.

Remarkably, the mice scratched much less in response to the triggers known to convey ‘histaminergic itch’, which has a range of causes, including bug bites and certain medications, that can set off the allergic response.

That result suggests TRPV4 in the top layer of skin is a main hub for detecting itch and is a promising drug target for treating the condition, said co-author Yong Chen, a senior research associate in Liedtke’s lab.

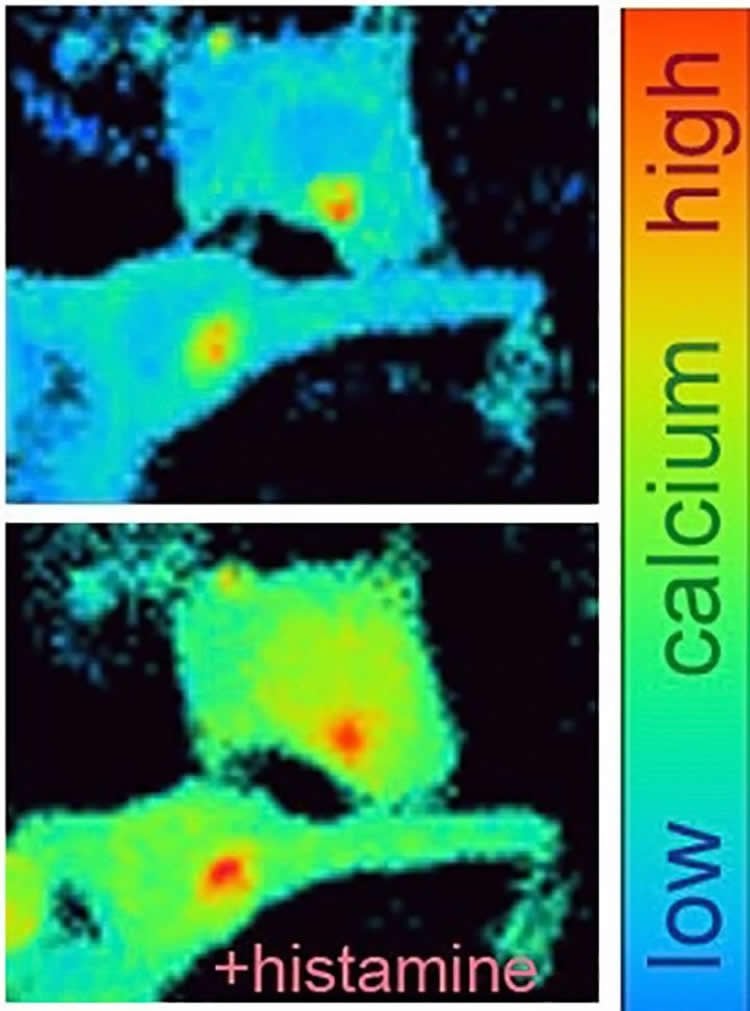

The scientists drilled down further into mechanisms inside skin cells, finding that TRPV4 triggers a rush of calcium into the cell and the flipping “on” of a molecular switch called ERK, (extracellular-signal-regulated kinase) into its activated form, pERK.

Drugs that block TRPV4 or pERK, when applied as topical ointments, quelled scratching in mice. Experiments in isolated mouse and human skin cells — the result of an ongoing collaboration with Jennifer Zhang, Amanda MacLeod and Russell Hall from Duke’s Department of Dermatology — further corroborated the group’s findings.

“For many decades, skin was believed to be a mere barrier, not endowed with sensory capability,” Chen said. “Now it turns out skin has features reminiscent of sensory-neural cells that are instrumental in facilitating the sensation of itch.”

TRPV4 is present on the surface of cells, which makes it an excellent target to reach with topically-applied drugs, Liedtke said. Before TRPV4 blockers could be used to treat people, however, they will need to be further formulated and then assessed in animals and human clinical trials.

In contrast, pERK is present not on the surface of skin cells but within them, and targeting it for the treatment of other conditions led to unwanted sideeffects. Liedtke is more skeptical of this approach.

Liedtke’s neuro-dermatology team is interested in understanding the cell-to-cell communication within skin, and what sustains itch over longer time periods. Moreover, individuals naturally have varying susceptibility to itch, and it will be important to understand whether underlying TRPV4 molecular pathways are involved in such differences.

“Such studies, combined with DNA sequencing, can perhaps accelerate the dawning of personalized medicine and its extension into the dermato-neurology arena,” Liedtke said.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DE018549, UL1TR001117, P30AR066527, F33DE024668, K12DE022793, 5K08AR063729-04) and the US Department of Defense (W81XWH-13-1-0299).

Source: Karl Bates – Duke University

Image Source: The image is credited to Yong Chen, Duke University.

Original Research: Abstract for “Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 ion channel functions as a pruriceptor in epidermal keratinocytes to evoke histaminergic itch” by Yong Chen, Quan Fang, Zilong Wang, Jennifer Y. Zhang, Amanda S. MacLeod, Russell P. Hall and Wolfgang B. Liedtke in Journal of Biological Chemistry. Published online March 9 2016 doi:10.1074/jbc.M116.716464

Abstract

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 ion channel functions as a pruriceptor in epidermal keratinocytes to evoke histaminergic itch

TRPV4 ion channels function in epidermal keratinocytes and in innervating sensory neurons, however, the contribution of the channel in either cell to neurosensory function remains to be elucidated. We recently reported TRPV4 as a critical component of the keratinocyte machinery that responds to UVB, and functions critically to convert the keratinocyte into a pain-generator cell after excess UVB exposure. One key mechanism in keratinocytes was increased expression and secretion of endothelin-1, which is also a known pruritogen. Here we address the question whether TRPV4 in skin keratinocytes functions in itch, as a particular form of forefront signaling in non-neural cells. Our results support this novel concept, based on attenuated scratching behavior in response to histaminergic (histamine, compound 48/80, endothelin-1), not non-histaminergic (chloroquine) pruritogens in Trpv4 keratinocyte-specific and inducible knockout mice. We demonstrate that keratinocytes rely on TRPV4 for calcium influx in response to histaminergic pruritogens. TRPV4 activation in keratinocytes evokes phosphorylation of MAP-kinase, ERK, for histaminergic pruritogens. This finding is relevant because we observed robust anti-pruritic effects with topical applications of selective inhibitors for TRPV4 and also for MEK, the kinase upstream of ERK, suggesting that calcium influx via TRPV4 in keratinocytes leads to ERK-phosphorylation, which in-turn rapidly converts the keratinocyte into an organismal itch-generator cell. In support of this concept we found that scratching behavior, evoked by direct intradermal activation of TRPV4, was critically dependent on TRPV4-expression in keratinocytes. Thus, TRPV4 functions as a pruriceptor-TRP in skin keratinocytes in histaminergic itch, a novel basic concept with translational-medical relevance.

“Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 ion channel functions as a pruriceptor in epidermal keratinocytes to evoke histaminergic itch” by Yong Chen, Quan Fang, Zilong Wang, Jennifer Y. Zhang, Amanda S. MacLeod, Russell P. Hall and Wolfgang B. Liedtke in Journal of Biological Chemistry. Published online March 9 2016 doi:10.1074/jbc.M116.716464