Summary: New research reveals that even a small loss of myelin—the protective coating around neurons—can severely disrupt how the brain sends and interprets sensory information. Studying corticothalamic circuits in mice, scientists found that when the first segment of myelin closest to the neuron’s cell body was degraded, nerve signals slowed and lost their crucial “first wave,” altering how sensory information was encoded.

This missing signal fragment changed how the cortex and thalamus communicated, leaving the brain unable to correctly identify when or what the whiskers were touching. The findings shed light on why grey matter lesions in disorders like multiple sclerosis lead to disorientation, memory lapses, and difficulty navigating everyday environments.

Key Facts:

- Critical Myelin Loss: Damage near the neuron’s cell body disrupted the first “code segment” needed for accurate signal transmission.

- Broken Communication Loops: Corticothalamic circuits still sent signals but with reduced accuracy, impairing sensory perception.

- Grey Matter Insight: The work explains why grey matter lesions produce severe cognitive symptoms in conditions like MS.

Source: KNAW

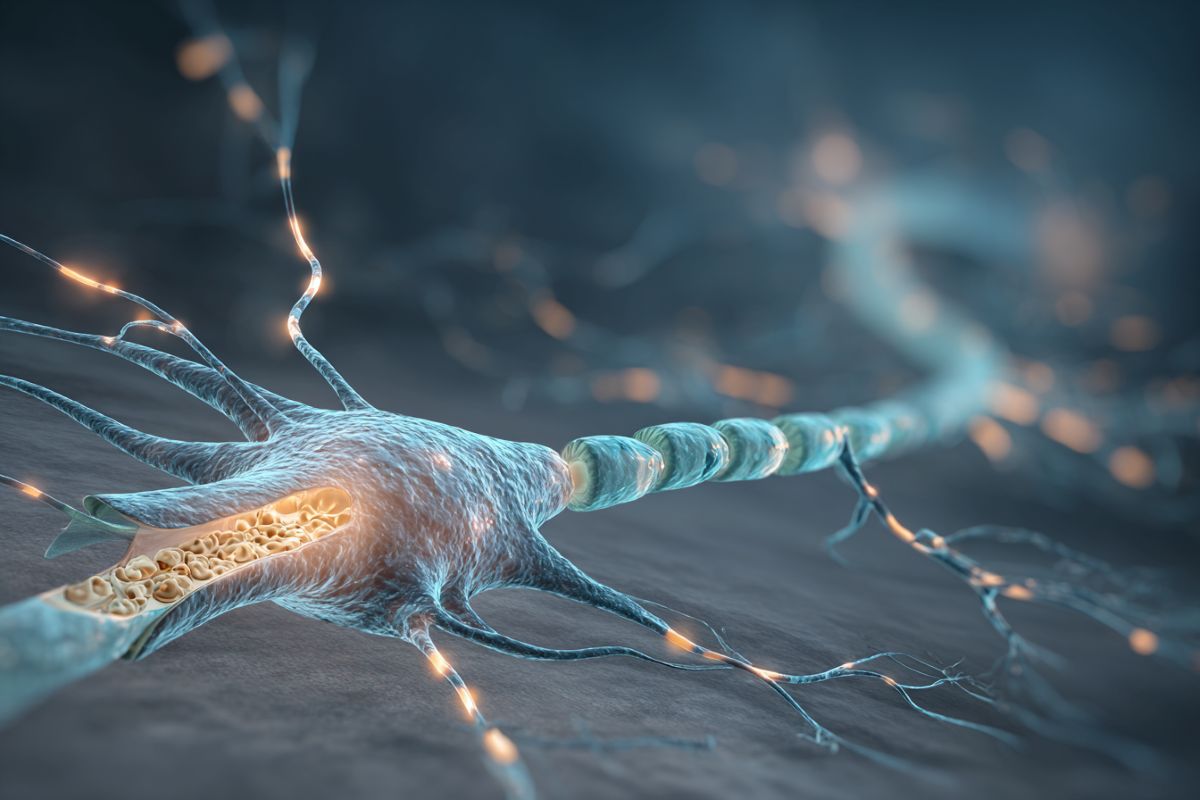

Our nerve cells are surrounded by a protective layer (myelin). This protective layer allows signals to pass between cells incredibly quickly. But what happens when this layer goes missing from cells that transfer signals over longer distances?

Maarten Kole’s research group studied this question in mice, looking specifically at nerve fibres travelling from the brain’s outer layer to the thalamus, a crucial switching station deep in the middle of the brain.

Processing sensory information involves continuous communication between the brain’s outer layer (cerebral cortex) and the thalamus. Such an exchange, for example, occurs when mice explore their environment with their whiskers. This interaction is known as a corticothalamic loop.

These loops also help humans process sensory information and perform all sorts of cognitive tasks. In Multiple Sclerosis (MS), damage to myelin can result in cognitive impairments, like not being able to recall familiar names.

The nerve cells that are most important for information exchange in these loops are those located in the fifth layer of the brain’s cerebral cortex.

“We actually understand these cells very well, but we didn’t know which role myelin played in the process of transferring information to the thalamus”, Maarten Kole, group leader at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, explains.

Targeted myelin degradation

To explore this role, the researchers administered a toxic substance that breaks down myelin. They expected that this would cause the entire nerve fibre to lose its myelin. But instead, the degradation only occurred in the parts located closest to the cell body.

This means that this method mostly imitates how MS develops in areas where the cell bodies are located: the so-called grey matter lesions. With such lesions, the cognitive problems are often more severe and the prognosis worse.

In these instances, people with MS can’t orient themselves properly anymore, notice problems when driving, and struggle to recall the names of people familiar to them.

Missing piece of code

The researchers discovered that the missing piece of myelin resulted in slower and less consistent signal transmission to the thalamus.

“We had anticipated this, because myelin is known to be essential for fast signal transmission”, Kole explains, “but what was new to us was that we lost the first wave of signals entirely”.

“You could compare it to a barcode in the supermarket: the scanner only recognises a product if you scan the entire barcode. But if you miss the first piece of myelin, then you’re essentially skipping the first black stripe of the barcode. Because of this, you can’t scan the right product anymore”.

Unrecognisable environment

But what is the exact impact of this missing piece of code? When the whiskers of a mouse touch an object, the cells in the brain’s cerebral cortex act as an amplifier of the thalamus. This amplification helps the mouse more accurately determine what and where it’s touching something.

“We saw that this amplification is still happening, but less accurately. Because of that, the communication loop between these two brain areas is disrupted, and the brain loses track. The mouse can still feel something with its whiskers, but it can’t exactly identify when or what”, Kole explains.

What does this mean?

Insight into the anatomy and workings of these specific nerve cells is important for future research.

“We’ve known for a while that these cells are wrapped in myelin in a very particular way”, Kole confesses.

“It’s one of the few cell types where the first part in particular is so specifically isolated. Now we finally understand why that’s the case”.

This knowledge forms a basis for our understanding of symptoms that develop with grey matter lesions. We know that the brain is continuously generating codes. When myelin on these nerve cells is lost, the codes change, and that communication in the brain is disrupted. This results in cognitive problems, like struggling to orient yourself.

In the future, Kole’s team wants to investigate how myelin damage in this area could be recovered. That way, the severe symptoms associated with the grey matter lesion in MS can one day be alleviated.

Key Questions Answered:

A: This segment carries the first “stripe” of the brain’s information code. Without it, the thalamus receives incomplete signals and can’t interpret input correctly.

A: Signals arrive slower and less reliably, so the brain knows something happened but can’t determine the “what” or “when,” leading to sensory confusion.

A: Grey matter lesions often strip myelin in this precise location, explaining why patients struggle with orientation, recognition, and other higher-order cognitive tasks.

Editorial Notes:

- This article was edited by a Neuroscience News editor.

- Journal paper reviewed in full.

- Additional context added by our staff.

About this sensory neuroscience and myelin research news

Author: NIN Communication

Source: KNAW

Contact: NIN Communication – KNAW

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Layer 5 myelination gates corticothalamic coincidence detection” by Maarten Kole et al. Nature Communications

Abstract

Layer 5 myelination gates corticothalamic coincidence detection

Myelin is essential for the rapid conduction of action potentials (APs) but its role in long-range processing of disparate inputs remains unclear.

Here, using a cell-type-specific approach we recorded optogenetically evoked pyramidal neuron responses via in vivo juxtacellular patch-clamp and Neuropixels probes, tracking spike transmission from layer 5 (L5) to the posteromedial thalamic nucleus (POm) in the mouse.

Cuprizone-induced demyelination caused millisecond-scale delays, increased temporal jitter and impaired transmission of high-frequency AP bursts. Computational modeling of the saltatory propagation from L5 to POm revealed that myelin loss from neocortical internodes acts as a low-pass filter, impeding high-frequency spikes within the burst.

Finally, pairing optogenetic stimulation with whisker input showed that intact myelination is crucial for coincidence detection in the thalamus.

These findings suggest that the continuous myelin pattern of L5 axons not only speeds conduction but also enables precise temporal integration of sensory and cortical signals across long-range pathways.