Summary: AMPA receptors form and disintegrate continually, rather than existing as stable entities. The findings shed light on the early stages of synaptic plasticity.

Source: Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

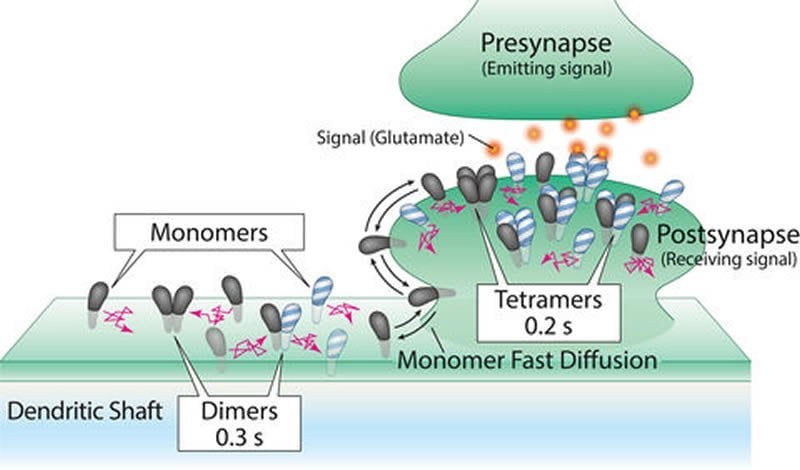

Synapses allow neurons to communicate with one another. In the synapse, one neuron emits chemical messengers called neurotransmitters, and an adjacent neuron receives them using tiny structures called receptors. A specific type of receptor, the AMPA receptor, plays a crucial role in learning and memory processes. However, scientists don’t yet fully understand how these AMPA receptors form and work.

Now, researchers in the Membrane Cooperativity Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) in Japan, in collaboration with researchers from universities across Japan, have found that AMPA receptors form and disintegrate continually, within a fraction of a second, rather than existing as stable entities. The scientists’ findings, published in Nature Communications, may clarify early stages of synaptic plasticity, neural activity that is key for learning and memory. The research may also have pharmacological applications in the treatment of epilepsy.

The changing brain

AMPA receptors are composed of four molecules, or subunits called GluA1, 2, 3 and 4, which unite to form structures called tetramers. Different combinations of the subunits form the tetramers; this means there are 256 possible configurations of AMPA receptor.

Scientists have long believed that these tetramers originate in the endoplasmic reticulum, the cell’s “manufacturing center,” before migrating to the synapses, all while retaining stable structures for hours or even days.

“This tetramer stability could actually be problematic for neurons,” said Professor Akihiro Kusumi, a co-author of the study. “The synapses need AMPA receptor tetramers with different combinations of subunits as the brain learns and its neuronal circuits change. Thus, we had a gut feeling that something was terribly wrong with the accepted notion of how AMPA receptors form, migrate, and work.”

Looking at AMPA receptors in motion at single-molecule resolutions

Following this intuition, the researchers put fluorescent tags on each individual subunit molecule of the AMPA receptors. Then, they tracked the molecules’ movements in live cells at nanometer-precisions. They used a single-molecule fluorescence microscope and software to analyze the motion of the single molecules, a method Kusumi and his colleagues pioneered.

By studying how the AMPA receptor molecules jostled around in the membrane and bound to each other, the researchers found that the AMPA receptor subunits existed as single molecules as well as assemblies two, three, and four molecules. Tetramers were found, but they fell apart in about 0.1 to 0.2 seconds. Then, however, the separated molecules found other partner molecules to form new assemblies of two, three and four molecules again, continually repeating this process.

In addition, the researchers found that when the molecules formed tetramers, albeit briefly, they worked as tiny channels that opened for less than 0.1 seconds. Since the functional tetramers are continually broken up to form new tetramers, AMPA receptor tetramers with different subunit compositions can readily be formed. This represents a novel mechanism for synaptic plasticity.

Kusumi noted that the team’s findings may have medical applications. Individuals with epilepsy have an excess of glutamate, the neurotransmitter that binds to AMPA receptors in the brain. These individuals are often treated with anticonvulsants that stop glutamate from binding to AMPA receptor tetramers, but these treatments can be too overpowering, and therefore ineffective.

Kusumi believes the development of drugs that slow down the formation of tetramers with certain subunit compositions in the brain could mitigate problematic types of synaptic plasticity, thus diminishing the symptoms of epilepsy.

Source:

Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

Media Contacts:

Anna Aaronson – Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

Image Source:

The image is credited to OIST.

Original Research: Open access

“AMPA receptors in the synapse turnover by monomer diffusion”. Jyoji Morise et al.

Nature Communications doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13229-8.

Abstract

AMPA receptors in the synapse turnover by monomer diffusion

The number and subunit compositions of AMPA receptors (AMPARs), hetero- or homotetramers composed of four subunits GluA1–4, in the synapse is carefully tuned to sustain basic synaptic activity. This enables stimulation-induced synaptic plasticity, which is central to learning and memory. The AMPAR tetramers have been widely believed to be stable from their formation in the endoplasmic reticulum until their proteolytic decomposition. However, by observing GluA1 and GluA2 at the level of single molecules, we find that the homo- and heterotetramers are metastable, instantaneously falling apart into monomers, dimers, or trimers (in 100 and 200 ms, respectively), which readily form tetramers again. In the dendritic plasma membrane, GluA1 and GluA2 monomers and dimers are far more mobile than tetramers and enter and exit from the synaptic regions. We conclude that AMPAR turnover by lateral diffusion, essential for sustaining synaptic function, is largely done by monomers of AMPAR subunits, rather than preformed tetramers.