Summary: Low to moderate stress can help build resilience and may reduce the risk of developing more serious mental health disorders including depression and anti-social behavior, a new study reports.

Source: University of Georgia

It may feel like an anvil hanging over your head, but that looming deadline stressing you out at work may actually be beneficial for your brain, according to new research from the Youth Development Institute at the University of Georgia.

Published in Psychiatry Research, the study found that low to moderate levels of stress can help individuals develop resilience and reduce the risk of developing mental health disorders, like depression and antisocial behaviors. Low to moderate stress can also help individuals to cope with future stressful encounters.

“If you’re in an environment where you have some level of stress, you may develop coping mechanisms that will allow you to become a more efficient and effective worker and organize yourself in a way that will help you perform,” said Assaf Oshri, lead author of the study and an associate professor in the College of Family and Consumer Sciences.

The stress that comes from studying for an exam, preparing for a big meeting at work or pulling longer hours to close the deal can all potentially lead to personal growth. Being rejected by a publisher, for example, may lead a writer to rethink their style. And being fired could prompt someone to reconsider their strengths and whether they should stay in their field or branch out to something new.

But the line between the right amount of stress and too much stress is a thin one.

“It’s like when you keep doing something hard and get a little callous on your skin,” continued Oshri, who also directs the UGA Youth Development Institute. “You trigger your skin to adapt to this pressure you are applying to it. But if you do too much, you’re going to cut your skin.”

Good stress can act as a vaccine against the effect of future adversity

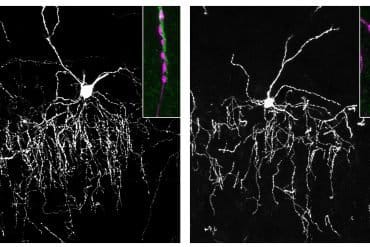

The researchers relied on data from the Human Connectome Project, a national project funded by the National Institutes of Health that aims to provide insight into how the human brain functions.

For the present study, the researchers analyzed the project’s data from more than 1,200 young adults who reported their perceived stress levels using a questionnaire commonly used in research to measure how uncontrollable and stressful people find their lives.

Participants answered questions about how frequently they experienced certain thoughts or feelings, such as “in the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?” and “in the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?”

Their neurocognitive abilities were then assessed using tests that measured attention and ability to suppress automatic responses to visual stimuli; cognitive flexibility, or ability to switch between tasks; picture sequence memory, which involves remembering an increasingly long series of objects; working memory and processing speed.

The researchers compared those findings with the participants’ answers from multiple measures of anxious feelings, attention problems and aggression, among other behavioral and emotional problems.

The analysis found that low to moderate levels of stress were psychologically beneficial, potentially acting as a kind of inoculation against developing mental health symptoms.

“Most of us have some adverse experiences that actually make us stronger,” Oshri said. “There are specific experiences that can help you evolve or develop skills that will prepare you for the future.”

But the ability to tolerate stress and adversity varies greatly according to the individual.

Things like age, genetic predispositions and having a supportive community to fall back on in times of need all play a part in how well individuals handle challenges. While a little stress can be good for cognition, Oshri warns that continued levels of high stress can be incredibly damaging, both physically and mentally.

“At a certain point, stress becomes toxic,” he said. “Chronic stress, like the stress that comes from living in abject poverty or being abused, can have very bad health and psychological consequences. It affects everything from your immune system, to emotional regulation, to brain functioning. Not all stress is good stress.”

The study was co-authored by Zehua Cui and Cory Carvalho, of the University of Georgia’s Department of Human Development and Family Science, and Sihong Liu, of Stanford University.

About this stress research news

Author: Cole Sosebee

Source: University of Georgia

Contact: Cole Sosebee – University of Georgia

Image: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Closed access.

“Is perceived stress linked to enhanced cognitive functioning and reduced risk for psychopathology? Testing the hormesis hypothesis” by Assaf Oshri et al. Psychiatry Research

Abstract

Is perceived stress linked to enhanced cognitive functioning and reduced risk for psychopathology? Testing the hormesis hypothesis

Extensive research documents the impact of psychosocial stress on risk for the development of psychiatric symptoms across one’s lifespan. Further, evidence exists that cognitive functioning mediates this link. However, a growing body of research suggests that limited stress can result in cognitive benefits that may contribute to resilience.

The hypothesis that low-to-moderate levels of stress are linked to more adaptive outcomes has been referred to as hormesis. Using a sample of young adults from the Human Connectome Project (N = 1,206, 54.4% female, Mage = 28.84), the present study aims to test the hormetic effect between low-to-moderate perceived stress and psychopathological symptoms (internalizing and externalizing symptoms), as well as to cross-sectionally explore the intermediate role of cognitive functioning in this effect.

Results showed cognitive functioning as a potential intermediating mechanism underlying the curvilinear associations between perceived stress and externalizing, but not internalizing, behaviors.

This study provides preliminary support for the benefits of limited stress to the process of human resilience.