Summary: A new study reveals reverting neurons to an early growth state can help reconnect severed spinal cord nerves in rodent models of SCI.

Source: NIH/NINDS.

For many years, researchers have thought that the scar that forms after a spinal cord injury actively prevents damaged neurons from regrowing. In a study of rodents, scientists supported by the National Institutes of Health showed they could overcome this barrier and reconnect severed spinal cord nerves by turning back the neurons’ clocks to put them into an early growth state. Once this occurs, neurons could be induced to regrow across the scarred tissue. The research was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), part of NIH.

“For decades researchers have been trying to make severed neurons regrow across a spinal cord injury and reconnect with neurons on the other side. This study suggests that may require manipulating three key growth processes,” said Lyn Jakeman, Ph.D., program director, NINDS. “These insights are important for understanding the mechanisms of injury and regeneration that may one day be applied to develop potential treatments for spinal cord injury.”

Neurons send signals to each other through long projections called axons. When the spinal cord is injured, many of these axons are severed, leading to a loss of sensation and/or paralysis below the injury site. In response, a scar forms within the damaged tissue, and while the axons may briefly attempt to regrow, this process is unsuccessful. Because these connections between neurons are made initially as the body is developing, researchers have sought to restore those developmental conditions to potentially help the damaged cord heal.

“There are several growth patterns in the spinal cord that shut down after development,” said Michael V. Sofroniew, M.D., Ph.D., professor at the Brain Research Institute at UCLA and senior author of the study published in Nature. “We wanted to see if we could reactivate those patterns following injury and whether that would lead to regrowth of the axons.”

Using both mouse and rat spinal cord injury models, the researchers from UCLA and their collaborators at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Lausanne, Switzerland, looked at three components of the regrowth process.

First, they tried to genetically turn back the neurons’ clock by reactivating the growth program that produced the original connections, specifically neurons that look like they are trying to regrow. While not active in adults, the neurons still carry the program used during early growth. By injecting viruses containing genes related to this program, the researchers were able to revert spinal cord neurons back to a state where axon growth could occur.

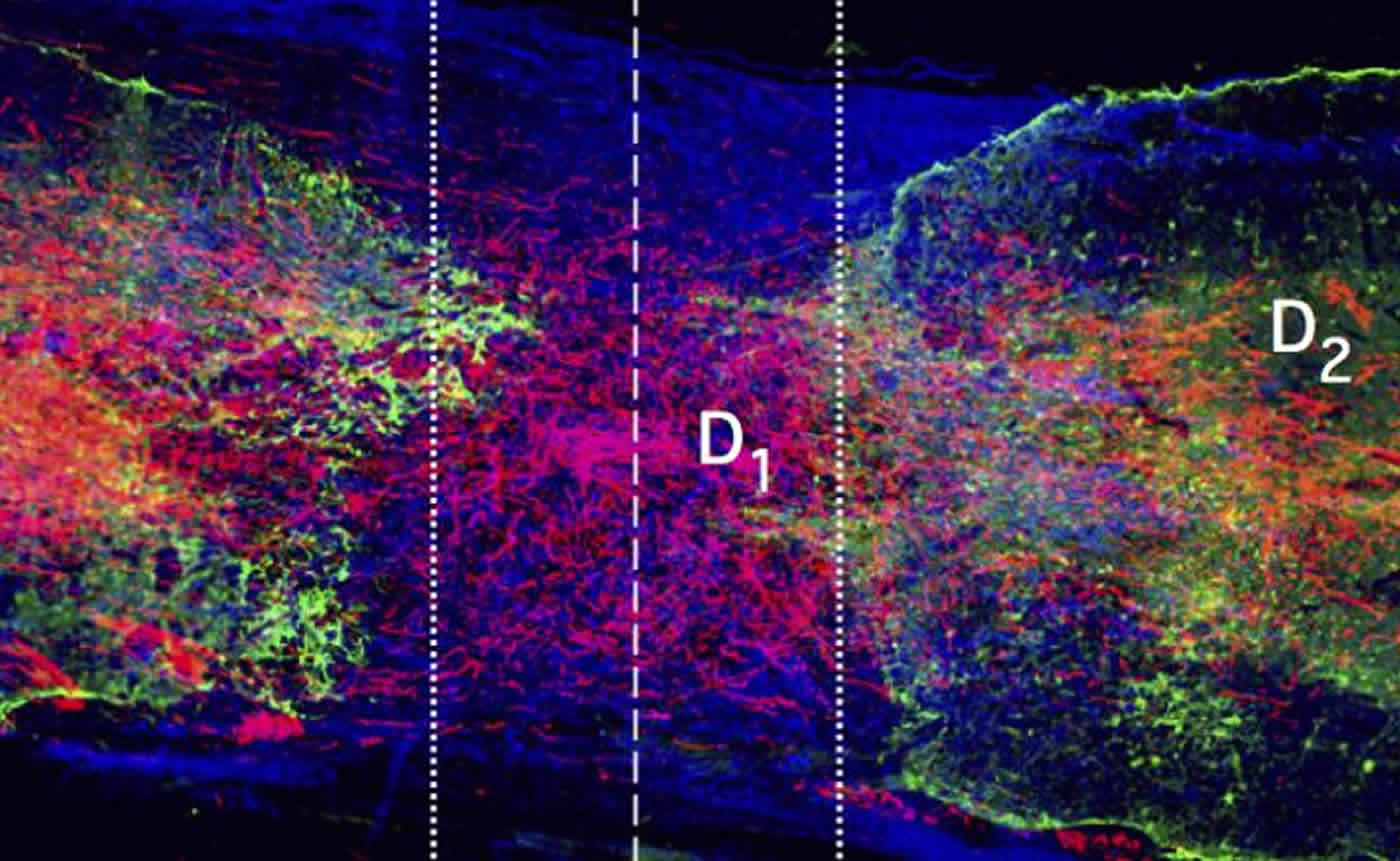

Second, the new axons needed to travel through the damaged tissue. Normally, growing axons move along highways paved with molecules that are not found in the scar tissue. After injecting the injury site with a gel containing a combination of growth-promoting proteins, the scientists saw an increase in axon-supportive molecules, effectively providing a “road” across the injury.

Finally, the growing axons needed to exit the injury site and find targets. During development, neurons release proteins called chemoattractants that axons home in on. To mimic this, the researchers injected chemoattractant proteins in a trail beyond the injury site and saw that these “chemical breadcrumbs” successfully led axons to grow completely through the injury site.

When any of the three treatments–viral activation of the growth program, formation of the path for axon travel, and the addition of chemoattractants–were not provided, minimal, if any regrowth was seen. In contrast, when all three were used in the order described, the neurons grew robustly. Tens or hundreds of axons traveled across the scar and reconnected with neurons on the other side.

Although their results suggest that the new connections could conduct electrical signals across the injury, the rodents could not move any better. However, Dr. Sofroniew emphasized that this was not unexpected.

“We would expect that these regrown axons would behave very much like the new axons we see in development,” he explained. “Much like a newborn must learn to walk, these newly formed circuits will probably require training before functional recovery can be seen.”

Spinal cord trauma affects roughly 12,500 people in the United States each year, and an estimated 276,000 individuals in the U.S. currently live with the long-term effects of spinal cord injury. The goal of research into spinal cord injury is to restore connections severed by the injury to provide functional recovery.

Dr. Sofroniew and his colleagues are now looking to continue to refine their understanding of the mechanisms involved in axon regeneration and to determine how newly wired circuits can best be retrained to restore movement.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants (NS084030, NS096858, NS096294, NS062691), the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Foundation, the International Foundation for Research in Paraplegia, Craig H. Neilsen Foundation, European Research Council, Swiss National Science Foundation, and Wings for Life.

Source: Carl Wonders – NIH/NINDS

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Sofroniew lab.

Original Research: Abstract for “Required growth facilitators propel axon regeneration across complete spinal cord injury” by Mark A. Anderson, Timothy M. O’Shea, Joshua E. Burda, Yan Ao, Sabry L. Barlatey, Alexander M. Bernstein, Jae H. Kim, Nicholas D. James, Alexandra Rogers, Brian Kato, Alexander L. Wollenberg, Riki Kawaguchi, Giovanni Coppola, Chen Wang, Timothy J. Deming, Zhigang He, Gregoire Courtine & Michael V. Sofroniew in Nature. Published August 29 2018.

doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0467-6

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]NIH/NINDS”An Early Recipe for Rewiring Spinal Cords.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 31 August 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/spinal-cord-repair-9774/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]NIH/NINDS(2018, August 31). An Early Recipe for Rewiring Spinal Cords. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved August 31, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/spinal-cord-repair-9774/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]NIH/NINDS”An Early Recipe for Rewiring Spinal Cords.” https://neurosciencenews.com/spinal-cord-repair-9774/ (accessed August 31, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Required growth facilitators propel axon regeneration across complete spinal cord injury

Transected axons fail to regrow across anatomically complete spinal cord injuries (SCI) in adults. Diverse molecules can partially facilitate or attenuate axon growth during development or after injury but efficient reversal of this regrowth failure remains elusive. Here we show that three factors that are essential for axon growth during development but are attenuated or lacking in adults—(i) neuron intrinsic growth capacity (ii) growth-supportive substrate and (iii) chemoattraction—are all individually required and, in combination, are sufficient to stimulate robust axon regrowth across anatomically complete SCI lesions in adult rodents. We reactivated the growth capacity of mature descending propriospinal neurons with osteopontin, insulin-like growth factor 1 and ciliary-derived neurotrophic factor before SCI1; induced growth-supportive substrates with fibroblast growth factor 2 and epidermal growth factor; and chemoattracted propriospinal axons with glial-derived neurotrophic factor delivered via spatially and temporally controlled release from biomaterial depots placed sequentially after SCI. We show in both mice and rats that providing these three mechanisms in combination, but not individually, stimulated robust propriospinal axon regrowth through astrocyte scar borders and across lesion cores of non-neural tissue that was over 100-fold greater than controls. Stimulated, supported and chemoattracted propriospinal axons regrew a full spinal segment beyond lesion centres, passed well into spared neural tissue, formed terminal-like contacts exhibiting synaptic markers and conveyed a significant return of electrophysiological conduction capacity across lesions. Thus, overcoming the failure of axon regrowth across anatomically complete SCI lesions after maturity required the combined sequential reinstatement of several developmentally essential mechanisms that facilitate axon growth. These findings identify a mechanism-based biological repair strategy for complete SCI lesions that could be suitable to use with rehabilitation models designed to augment the functional recovery of remodelling circuits.