A new study out today in the journal Translational Psychiatry sheds further light on the idea that schizophrenia is a sensory disorder and that individuals with the condition are impaired in their ability to process stimuli from the outside world. The findings may also point to a new way to identify the disease at an early stage and before symptoms become acute.

Because one of the hallmarks of the disease is auditory hallucinations, such as hearing voices, researchers have long suspected a link between auditory processing and schizophrenia. The new study provides evidence that the filtering of incoming visual information, and also of simple touch inputs, is also severely compromised in individuals with the condition.

“When we think about schizophrenia, the first things that come to mind are the paranoia, the delusions, the disorganized thinking,” said John Foxe, Ph.D., the chair of the University of Rochester Medical Center Department of Neuroscience and senior author of the study. “But there is increasing evidence that there is something fundamentally wrong with the way these patients hear, the way they feel things through their sense of touch, and in the way in which they see the environment.”

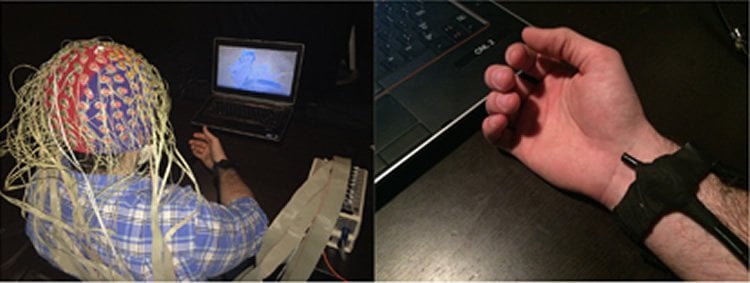

The researchers conducted a series of experiments in which they presented visual and touch stimuli to 15 schizophrenia patients and 15 controls while they recorded the brain’s response via electrodes placed on the surface of the scalp. What scientists have known for years is that when encountering a series of inputs, such as successive flashes of light, the brain’s initial response is large and strong. However, as the flash is repeated the reaction quickly fades in intensity.

This response reduction is known as sensory “adaptation” and is an essential mechanism which enables the brain to filter out repetitive and irrelevant information. Researchers believe that adaptation allows the brain to free itself up to respond to new events and stimuli that may be more important.

The research team found that adaptation was substantially weaker in the patients with schizophrenia, and this was the case for both repeated visual stimulation and for repeated touch stimulation.

“If you can’t properly filter the information at the basic sensory input stage, then it is not too hard to imagine how the external world could begin to be experienced as bizarre and unreliable,” said Gizely Andrade, Ph.D. with the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and a co-author of the study. “A fundamental aspect of the way our minds operate is that they can rely on the fact that the external world remains constant. If it doesn’t, then reality itself could become distorted.”

The team is hopeful that this discovery might lead to simple and basic measures of sensory adaptation that could be used to diagnose schizophrenia or identify individuals at risk of developing the condition before the disease has had a chance to fully establish itself.

“A key point with this study is that we find these dramatic differences in patients who are already suffering from full-blown schizophrenia,” said Foxe. “Schizophrenia is a disease that typically strikes during late adolescence or early adulthood, but what we also know is that long before a person has their first major psychotic episode, there are subtle changes occurring that precede the full manifestation of the disease. Our hope is that these new measures can allow us to pick up on these people before they ever become seriously ill.”

Additional co-authors of the study include Gregory Peters and Sophie Molholm with the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and John Butler of the Dublin Institute of Technology in Ireland.

Funding: The research was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Source: Mark Michaud – University of Rochester Medical Center

Image Source: The image is credited to G N Andrade, J S Butler, G A Peters, S Molholm, J J Foxe/Translational Psychiatry and is adapted from the open access research paper.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Atypical visual and somatosensory adaptation in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders” by G N Andrade, J S Butler, G A Peters, S Molholm and J J Foxe in Translational Psychiatry. Published online May 10 2016 doi:10.1038/tp.2016.63

Abstract

Atypical visual and somatosensory adaptation in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders

Neurophysiological investigations in patients with schizophrenia consistently show early sensory processing deficits in the visual system. Importantly, comparable sensory deficits have also been established in healthy first-degree biological relatives of patients with schizophrenia and in first-episode drug-naive patients. The clear implication is that these measures are endophenotypic, related to the underlying genetic liability for schizophrenia. However, there is significant overlap between patient response distributions and those of healthy individuals without affected first-degree relatives. Here we sought to develop more sensitive measures of sensory dysfunction in this population, with an eye to establishing endophenotypic markers with better predictive capabilities. We used a sensory adaptation paradigm in which electrophysiological responses to basic visual and somatosensory stimuli presented at different rates (ranging from 250 to 2550 ms interstimulus intervals, in blocked presentations) were compared. Our main hypothesis was that adaptation would be substantially diminished in schizophrenia, and that this would be especially prevalent in the visual system. High-density event-related potential recordings showed amplitude reductions in sensory adaptation in patients with schizophrenia (N=15 Experiment 1, N=12 Experiment 2) compared with age-matched healthy controls (N=15 Experiment 1, N=12 Experiment 2), and this was seen for both sensory modalities. At the individual participant level, reduced adaptation was more robust for visual compared with somatosensory stimulation. These results point to significant impairments in short-term sensory plasticity across sensory modalities in schizophrenia. These simple-to-execute measures may prove valuable as candidate endophenotypes and will bear follow-up in future work.

“Atypical visual and somatosensory adaptation in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders” by G N Andrade, J S Butler, G A Peters, S Molholm and J J Foxe in Translational Psychiatry. Published online May 10 2016 doi:10.1038/tp.2016.63