Summary: A new study reveals people respond to stimuli in another person’s peripersonal space as they could their own.

Source: Kumamoto University.

Peripersonal space (PPS) is an area created by the brain immediately around one’s own body parts that is used when interacting with people and objects. Recently, researchers have shown that some neurons in the primate brain respond to an infringement of another person’s PPS as if their own space was being encroached upon. To determine how this “PPS remapping” phenomenon affects human behavior, Kumamoto University researcher, Dr. Wataru Teramoto, evaluated people’s reactions to visual or tactical stimuli while alone or with a partner. He found that participants responded to stimuli in a partner’s PPS as quickly as they would their own.

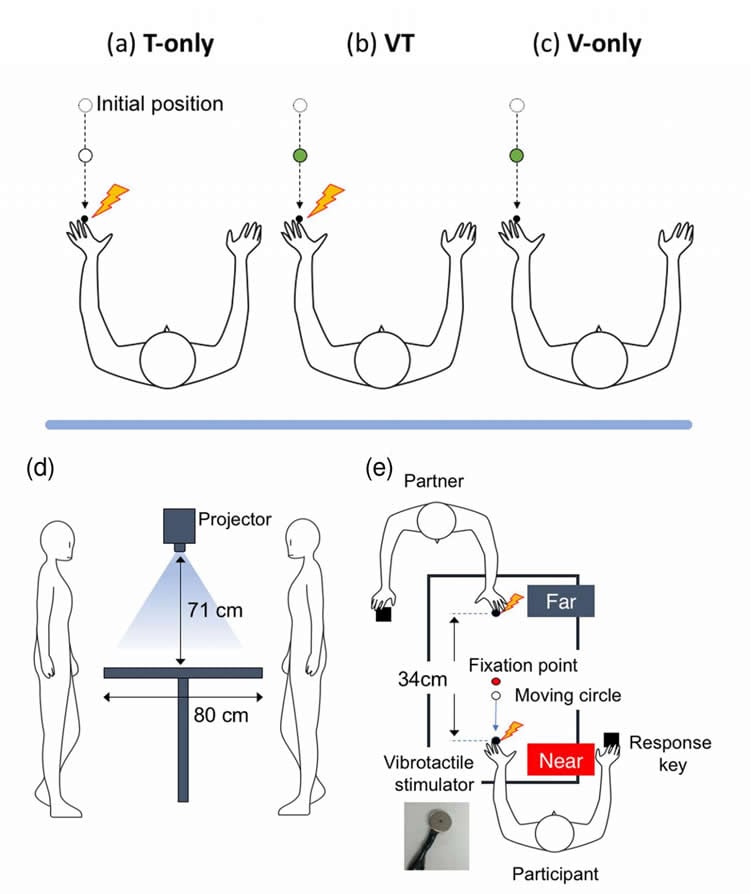

The experimental setup used three types of stimuli, tactile only (T-only), visual only, (V-only), and visuotactile (VT) for multiple kinds of experiments. Participants were instructed to press a button with their right hand as quickly as possible in response to any of the three stimuli: a vibration in their left index finger, a change in color of a moving disk (white to green) projected onto the table in front of them, or a combination of the two. Experiments were performed alone, with a partner, or with a fake (rubber) arm. The visual stimuli appeared either inside or outside of the participant’s PPS, with the latter space corresponding to the partner’s PPS.

“Participant responses should be similar between approaching (toward the participant, in the participant’s PPS) and receding (toward a partner, in the partner’s PPS) stimuli if PPS remapping is a naturally occurring phenomenon,” said Dr. Teramoto. “And my data has shown strong behavioral evidence supporting remapping.”

Indeed, the participants in the first experiment responded more quickly to stimuli approaching them or their partner compared to when the stimuli receded from them when no partner was present. The second experiment showed the effect even when the participants did not know their partner, and showed that it was not present when a fake arm was used instead of a partner. In the third experiment, the PPS remapping effect was seen even when the participant and partner used different body parts.

“The brain appears not only to be able to show us when something is nearing us, but it is also able to let us know when it is happening to someone else,” finished Dr. Teramoto. “Further research into this effect is certainly warranted to clarify some of the issues that appeared in this experiment, such as the effect of distance on receding stimuli or whether a certain direction of movement is favored.”

Funding: Funding provided by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Source: J. Sanderson – Kumamoto University

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Dr. Wataru Teramoto.

Original Research: Open access research for “A behavioral approach to shared mapping of peripersonal space between oneself and others” by Wataru Teramoto in Scientific Reports. Published April 33 2018.

doi:10.1038/s41598-018-23815-3

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Kumamoto University “Your Brain Considers Other People’s Personal Space as Your Own.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 7 June 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/personal-space-9283/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Kumamoto University (2018, June 7). Your Brain Considers Other People’s Personal Space as Your Own. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved June 7, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/personal-space-9283/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Kumamoto University “Your Brain Considers Other People’s Personal Space as Your Own.” https://neurosciencenews.com/personal-space-9283/ (accessed June 7, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

A behavioral approach to shared mapping of peripersonal space between oneself and others

Recent physiological studies have showed that some visuotactile brain areas respond to other’s peripersonal spaces (PPS) as they would their own. This study investigates this PPS remapping phenomenon in terms of human behavior. Participants placed their left hands on a tabletop screen where visual stimuli were projected. A vibrotactile stimulator was attached to the tip of their index finger. While a white disk approached or receded from the hand in the participant’s near or far space, the participant was instructed to quickly detect a target (vibrotactile stimulation, change in the moving disk’s color or both). When performing this task alone, the participants exhibited shorter detection times when the disk approached the hand in their near space. In contrast, when performing the task with a partner across the table, the participants exhibited shorter detection times both when the disk approached their own hand in their near space and when it approached the partner’s hand in the partner’s near space but the participants’ far space. This phenomenon was also observed when the body parts from which the visual stimuli approached/receded differed between the participant and partner. These results suggest that humans can share PPS representations and/or body-derived attention/arousal mechanisms with others.