Summary: Memory decline that starts during middle age may be the result of changes in what information the brain focuses on when forming and retrieving memories.

Source: McGill University.

Research sheds new light on what constitutes healthy aging of the brain.

The inability to remember details, such as the location of objects, begins in early midlife (the 40s) and may be the result of a change in what information the brain focuses on during memory formation and retrieval, rather than a decline in brain function, according to a study by McGill University researchers.

Senior author Natasha Rajah, Director of the Brain Imaging Centre at McGill University’s Douglas Institute and Associate Professor in McGill’s Department of Psychiatry, says this reorientation could impact daily life. “This change in memory strategy with age may have detrimental effects on day-to-day functions that place emphasis on memory for details such as where you parked your car or when you took your prescriptions.”

Brain changes associated with dementia are now thought to arise decades before the onset of symptoms. So a key question in current memory research concerns which changes to the aging brain are normal and which are not. But Dr. Rajah says most of the work on aging and memory has concentrated on understanding brain changes later in life. “So we know little about what happens at midlife in healthy aging and how this relates to findings in late life. Our research was aimed at addressing this issue.”

In this study, published in the journal, NeuroImage, 112 healthy adults ranging in age from 19 to 76 years were shown a series of faces. Participants were then asked to recall where a particular face appeared on the screen (left or right) and when it appeared (least or most recently). The researchers used functional MRI to analyze which parts of brain were activated during recall of these details.

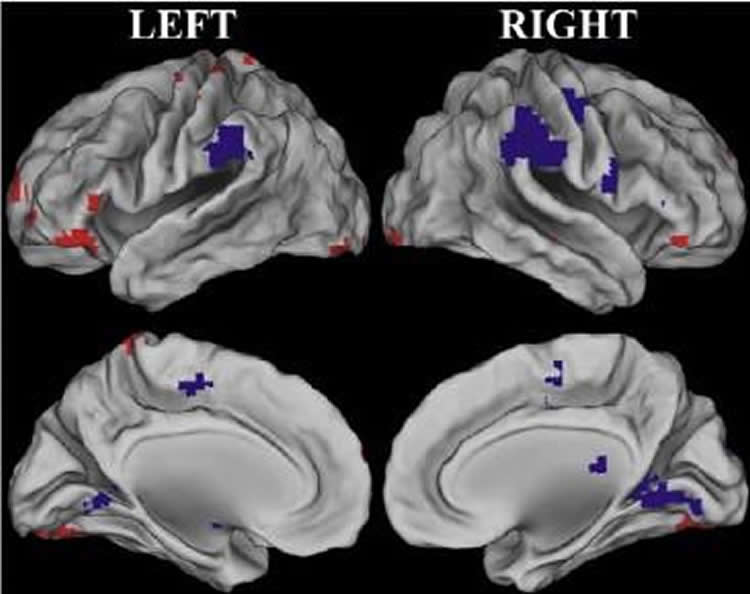

Rajah and colleagues found that young adults activated their visual cortex while successfully performing this task. As she explains, “They are really paying attention to the perceptual details in order to make that decision.” On the other hand, middle-aged and older adults didn’t show the same level of visual cortex activation when they recalled the information. Instead, their medial prefrontal cortex was activated. That’s a part of the brain known to be involved with information having to do with one’s own life and introspection.

Even though middle-aged and older participants didn’t perform as well as younger ones in this experiment, Rajah says it may be wrong to regard the response of the middle-aged and older brains as impairment. “This may not be a ‘deficit’ in brain function per se, but reflects changes in what adults deem ‘important information’ as they age.” In other words, the middle-aged and older participants were simply focusing on different aspects of the event compared to those in the younger group.

Rajah says that middle-aged and older adults might improve their recall abilities by learning to focus on external rather than internal information. “That may be why some research has suggested that mindfulness meditation is related to better cognitive aging.”

Rajah is currently analyzing data from a similar study to discern if there are any gender differences in middle-aged brain function as it relates to memory. “At mid-life women are going through a lot of hormonal change. So we’re wondering how much of these results is driven by post-menopausal women.”

Funding: This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Society of Canada.

Source: Cynthia Lee – McGill University

Image Source: This NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to N. Rajah, McGill University.

Original Research: Abstract for “Changes in the modulation of brain activity during context encoding vs. context retrieval across the adult lifespan” by E. Ankudowich, S. Pasvanis, and M.N. Rajah in NeuroImage. Published online June 14 2016 doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.06.022

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]McGill University. “New Clue to How Lithium Works in the Brain.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 12 July 2016.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/middle-age-memory-focus-4662/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]McGill University. (2016, July 12). New Clue to How Lithium Works in the Brain. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved July 12, 2016 from https://neurosciencenews.com/middle-age-memory-focus-4662/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]McGill University. “New Clue to How Lithium Works in the Brain.” https://neurosciencenews.com/middle-age-memory-focus-4662/ (accessed July 12, 2016).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Changes in the modulation of brain activity during context encoding vs. context retrieval across the adult lifespan

Age-related deficits in context memory may arise from neural changes underlying both encoding and retrieval of context information. Although age-related functional changes in the brain regions supporting context memory begin at midlife, little is known about the functional changes with age that support context memory encoding and retrieval across the adult lifespan. We investigated how age-related functional changes support context memory across the adult lifespan by assessing linear changes with age during successful context encoding and retrieval. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we compared young, middle-aged and older adults during both encoding and retrieval of spatial and temporal details of faces. Multivariate behavioral partial least squares (B-PLS) analysis of fMRI data identified a pattern of whole brain activity that correlated with a linear age term, and a pattern of whole brain activity that was associated with an age-by-memory phase (encoding vs. retrieval) interaction. Further investigation of this latter effect identified three main findings: 1) reduced phase-related modulation in bilateral fusiform gyrus, left superior/anterior frontal gyrus and right inferior frontal gyrus that started at midlife and continued to older age, 2) reduced phase-related modulation in bilateral inferior parietal lobule that occurred only in older age, and 3) changes in phase-related modulation in older but not younger adults in left middle frontal gyrus and bilateral parahippocampal gyrus that was indicative of age-related over-recruitment. We conclude that age-related reductions in context memory arise in midlife and are related to changes in perceptual recollection and changes in fronto-parietal retrieval monitoring.

“Changes in the modulation of brain activity during context encoding vs. context retrieval across the adult lifespan” by E. Ankudowich, S. Pasvanis, and M.N. Rajah in NeuroImage. Published online June 14 2016 doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.06.022