Summary: Researchers have developed a breakthrough technology using magnetic fields to control specific brain circuits non-invasively, potentially transforming treatments for conditions like Parkinson’s and depression. This technique, termed “magnetogenetics,” delivers gene therapy to target neurons and uses magnetic fields to activate or inhibit them, allowing precise manipulation without invasive implants.

In mouse studies, this approach successfully reduced movement issues associated with Parkinson’s. Future research aims to explore clinical applications for psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, providing a new frontier in brain circuit modulation.

Key Facts:

- Magnetogenetics enables control of neuron activity using magnetic fields, avoiding implants.

- Initial tests in mice demonstrated significant reductions in Parkinson’s-related movement issues.

- This technology may expand therapeutic options for neurological and psychiatric conditions.

Source: Weill Cornell Medicine

A new technology enables the control of specific brain circuits non-invasively with magnetic fields, according to a preclinical study from researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine, The Rockefeller University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The technology holds promise as a powerful tool for studying the brain and as the basis for future neurological and psychiatric treatments for conditions as diverse as Parkinson’s disease, depression, obesity and complex pain.

The new gene-therapy technology is described in a paper published Oct. 9 in Science Advances.

The researchers performed experiments in mice showing that it can switch on or off selected populations of neurons, with clear effects on the animals’ movements. In one experiment, they used it to reduce abnormal movements in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease.

“We envision that magnetogenetics technology may someday be used to benefit patients in a wide range of clinical settings,” said study senior author Dr. Michael Kaplitt, professor and executive vice-chairman of neurological surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine and director of Movement Disorders Surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

The study was a collaboration between Dr. Kaplitt’s laboratory and the laboratories of Dr. Jeffrey Friedman, the Marilyn M. Simpson Professor in the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics at The Rockefeller University; and Dr. Sarah Stanley, an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai.

The study’s first author was Dr. Santiago Unda, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Kaplitt’s laboratory.

Controlling brain circuits in real-time, in a way that allows animals—or humans—to move around normally, has been a major goal for neuroscientists, but a very challenging one. In the laboratory, optogenetics technology, for example, can make selected neurons switch on or off immediately with light pulses, but requires an invasive apparatus for delivering those light pulses to the brain.

In the clinic, deep brain stimulation permits modulation of brain regions, but this also requires a permanently implanted device and greater precision also remains a goal.

After doing early work on magnetogenetic technology as an alternative to other approaches, Dr. Friedman and Dr. Stanley joined forces with Dr. Kaplitt, a pioneer of brain-targeted gene therapies, to develop a method of this type with the potential for clinical applications.

The resulting approach uses gene therapy techniques to deliver an engineered ion-channel protein to a desired type of neuron. The ion channel protein essentially works as a switch to turn affected neurons on or off, and is sensitive to a magnetic field because it includes an antibody-like protein that sticks to a natural iron-trapping protein called ferritin.

While the gene therapy is delivered to precise brain regions through a minimally invasive surgery, a sufficiently strong magnetic field can then exert enough force on the ferritin-trapped iron atoms to open or close the channel—activating the neuron or inhibiting it, depending on the design, without the need for an implanted device or drug.

In one proof of concept, the team injected the gene therapy for the magnetically sensitive channels into specific neurons within a movement-controlling region called the striatum in mice; they then used the magnetic field from a magnetic resonance imaging machine to activate the neurons and markedly slow, even freeze, the mice’s movements.

In another experiment, they reduced neuronal activity in a brain region called the subthalamic nucleus to ameliorate movement abnormalities in a parkinsonism mouse model.

The researchers showed that their method can work even when using a much smaller and less expensive “transcranial magnetic stimulation” device, which is often used currently in the clinic to treat patients with depression, migraine and other conditions.

The experiments uncovered no safety issues, and the researchers note that normal ambient magnetic fields would be far too weak to trigger magnetogenetic switches inadvertently.

The team now intends to explore potential clinical applications including treatments for psychiatric disorders and even chronic pain in peripheral nerves. They also will continue to explore and optimize the magnetogenetics technology itself.

“Being able now to do directional manipulations of brain activity with this relatively simple system is going to be very important in helping us better understand the underlying principles to help further advancethis new technology,” Dr. Unda said.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the NIH Office of the Director, both part of the National Institutes of Health, through grant numbers R01NS097184, OT2OD024912, and the JPB Foundation.

About this magnetogenetics research news

Author: Eliza Powell

Source: Weill Cornell University

Contact: Eliza Powell – Weill Cornell University

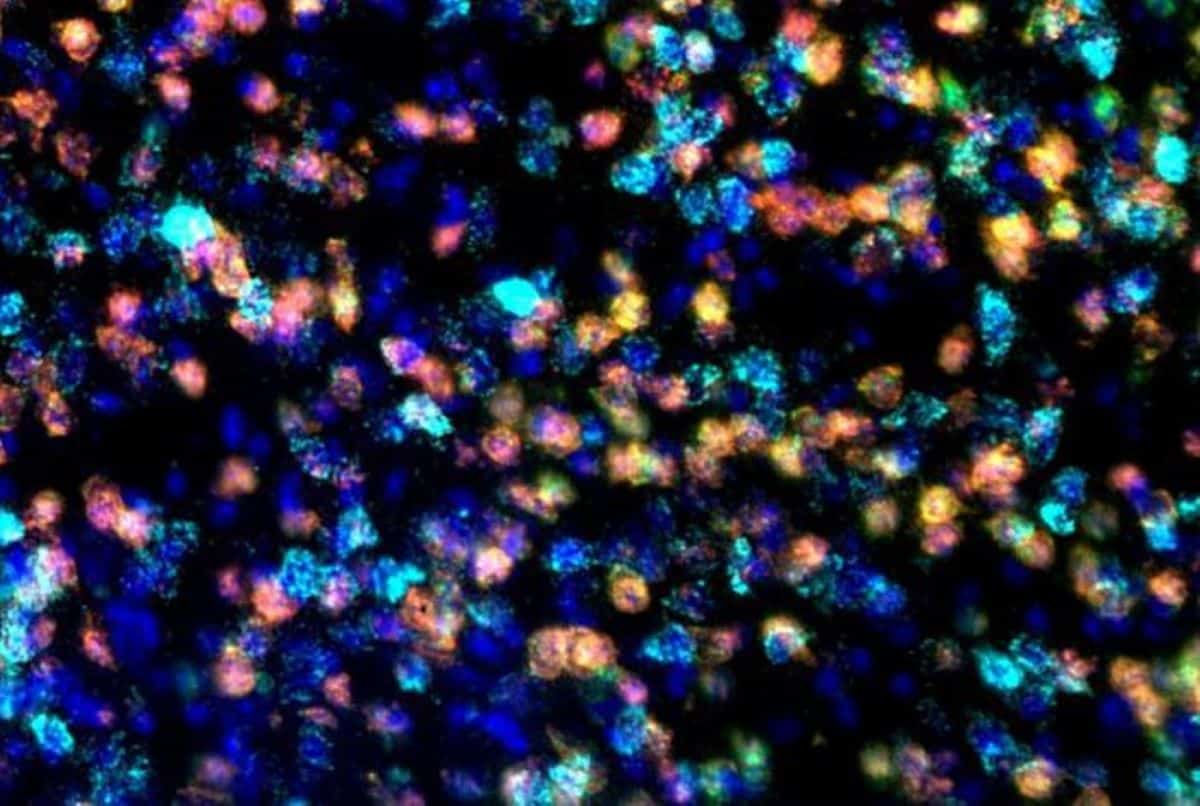

Image: The image is credited to Santiago Unda

Original Research: Open access.

“Bidirectional regulation of motor circuits using magnetogenetic gene therapy” by Michael Kaplitt et al. Science Advances

Abstract

Bidirectional regulation of motor circuits using magnetogenetic gene therapy

Here, we report a magnetogenetic system, based on a single anti-ferritin nanobody-TRPV1 receptor fusion protein, which regulated neuronal activity when exposed to magnetic fields.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)–mediated delivery of a floxed nanobody-TRPV1 into the striatum of adenosine-2a receptor–Cre drivers resulted in motor freezing when placed in a magnetic resonance imaging machine or adjacent to a transcranial magnetic stimulation device.

Functional imaging and fiber photometry confirmed activation in response to magnetic fields. Expression of the same construct in the striatum of wild-type mice along with a second injection of an AAVretro expressing Cre into the globus pallidus led to similar circuit specificity and motor responses.

Last, a mutation was generated to gate chloride and inhibit neuronal activity. Expression of this variant in the subthalamic nucleus in PitX2-Cre parkinsonian mice resulted in reduced c-fos expression and motor rotational behavior.

These data demonstrate that magnetogenetic constructs can bidirectionally regulate activity of specific neuronal circuits noninvasively in vivo using clinically available devices.