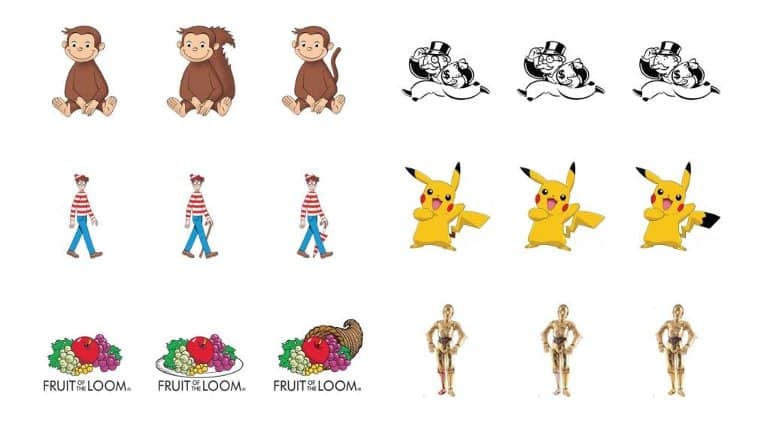

Summary: When it comes to famous logos and characters, people often experience a Visual Mandela Effect, or consistent, confident, and widespread false memories of such famous icons.

Source: University of Chicago

If you had to describe Rich Uncle Pennybags—the Monopoly mascot—would you mention his top hat? His mustache? How about his monocle?

The face of the famous board game has, in reality, never worn a monocle. Yet, many people confidently list the accessory when recalling his features—an example of a phenomenon of false visual memories.

A forthcoming paper by University of Chicago scholars, currently available in preprint, found that people have consistent, confident, and widespread false memories of famous icons—also known as the Visual Mandela Effect. Co-authored by University of Chicago scholars, the paper is the first scientific study of the internet phenomenon.

Forthcoming in the journal Psychological Science, the paper adds to a growing body of evidence showing consistency in what people remember—but by demonstrating new evidence that there is also consistency in what people misremember.

“This effect is really fascinating because it reveals that there are these consistencies across people in false memories that they have for images they’ve actually never seen,” said Asst. Prof. Wilma Bainbridge, a neuroscientist and principal investigator at the Brain Bridge Lab in UChicago’s Department of Psychology.

Motivated by reports of misremembered images online, Bainbridge and Deepasri Prasad—a lab manager and research assistant in the Brain Bridge Lab—compiled images and their false-remembered counterparts—mostly from popular culture—from the online discussions. Added to this mix of previously reported misremembered images were other pop culture icons and characters that the researchers made small tweaks to that would further test their theory.

The team set out to test four ideas. The first and main goal was to determine how widespread and consistent the Visual Mandela Effect was across individuals for the 40 different icons that they assembled. They also wanted to see where people were still making these errors—even if they’re very familiar and confident with their responses and with the characters.

Second, they wanted to know the underlying causes: Is it that people are just not looking at where this error is on the image? In the third experiment, they looked to quantify how common these false memory images are in the world by looking at Google Images. In the fourth experiment, they studied whether people spontaneously produce these errors: If asked to draw an image from memory, they often make the same errors.

“We found that there really is a strong effect where people are reporting a false memory for an image they’ve actually never seen—because you’ve never seen Pikachu with a black tip on the tail,” said Bainbridge, referring to a common false memory of the Pokémon character.

“What’s more is that people tend to be very confident in picking this wrong image. And they also report that they’re pretty familiar with characters like Pikachu—yet they still make these errors.”

The researchers haven’t yet been able to pinpoint a single reason for why this happens, but they have eliminated a few possibilities. The visual differences aren’t striking across the different versions, so people aren’t looking at the images differently. So even if people look at the correct version of that part of the image (say, Pikachu’s tail), they still make this error.

They also ruled out schema theory as a universal explanation. Schema theory suggests we fill in the information that’s missing based on our associations. This would explain why so many people misremember Rich Uncle Pennybags (also known as Mr. Monopoly) as having a monocle, because we associate the accessory with wealth.

But the researchers found examples where this doesn’t fit. For example, people often falsely remember the Fruit of the Loom logo having a large cornucopia behind it—even though cornucopias aren’t very common in everyday life.

“We had an alternative wrong version as well,” Prasad said.

“They could have picked the correct Fruit of the Loom logo, the Fruit of the Loom logo with the cornucopia, or the Fruit of the Loom logo with a plate underneath it. The fact that they chose cornucopia over plate, when plates are more frequently associated with fruit, is evidence against the idea that it’s just the schema theory explaining it.”

One of the big questions in the Brain Bridge Lab is why people remember certain things over others. So far, the researchers have found that people tend to remember and forget the same things.

“You would think that because all of us have our own individual experiences throughout our lives that we’d all have these idiosyncratic differences in our memories,” Bainbridge said.

“But surprisingly, we find that we tend to remember the same faces and pictures as each other. This consistency in our memories is really powerful, because this means that I can know how memorable certain pictures are, I could quantify it. I could even manipulate the memorability of an image.”

In finding that there’s an intrinsic ability in some images to create false memories, the research suggests we may also be able to determine what creates false memories.

“It also has some interesting implications in terms of logo design or how to select photographs for educational material and advertisement, because you want people to have accurate memories,” Bainbridge said. “You don’t want them to misremember information. And that actually relates a lot to some other important topics right now, including what images are used in the media.”

About this visual neuroscience research news

Author: Sarah Steimer

Source: University of Chicago

Contact: Sarah Steimer – University of Chicago

Image: The image is credited to University of Chicago

Original Research: Closed access.

“The Visual Mandela Effect as evidence for shared and specific false memories across people” by Wilma Bainbridge et al. Psychological Science

Abstract

The Visual Mandela Effect as evidence for shared and specific false memories across people

The Mandela Effect is an internet phenomenon describing shared and consistent false memories for specific icons in popular culture. The Visual Mandela Effect (VME) is a Mandela Effect specific to visual icons (e.g., the Monopoly Man is falsely remembered with a monocle) and has not yet been empirically quantified or tested.

In Experiment 1 (N=100), we demonstrate that certain images from popular iconography elicit consistent, specific false memories. In Experiment 2 (N=60), using eye-tracking-like methods, we find no attentional or visual differences that drive this phenomenon. There is no clear difference in the natural visual experience of these images (Experiment 3), and these VME-errors also occur spontaneously during recall (Experiment 4; N=50).

These results demonstrate that there are certain images for which people consistently make the same false memory error, despite majority of visual experience being the canonical image.