Summary: An international team of researchers have been able to demonstrate, with electrophysiological evidence, the existence of grid-like activity in the human brain.

Source: Max Planck Institute.

It has long been known that so-called place cells in the human hippocampus are responsible for coding one’s position in space. A related type of brain cell, called grid cells, encodes a variety of positions that are evenly distributed across space. This results in a kind of honeycomb pattern tiling the space. The cells exhibiting this pattern were discovered in the entorhinal cortex. How exactly the grid cell system works in the human brain, and in particular with which temporal dynamics, has until now been speculation. A much-discussed possibility is that the signals from these cells create maps of “cognitive spaces” in which humans mentally organize and store the complexities of their internal and external environments.

A European-American team of scientists has now been able to demonstrate, with electrophysiological evidence, the existence of grid-like activity in the human brain. Under the direction of Prof. Christian Doeller of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences (MPI CBS) in Leipzig and Dr. Tobias Staudigl of the Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behavior, Radboud University, The Netherlands, researchers used various methods to visualize grid cell activity while subjects explored images of everyday scenes. “We assume that these spatial coding principles in the brain form the basis of higher cognitive performance–here in this study, in the field of perception, but possibly also in decision-making or even in social interaction,” explained Prof. Doeller, who is now continuing his research as the new director of the MPI CBS in Leipzig.

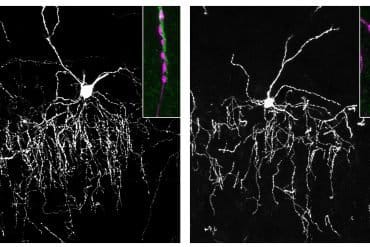

To demonstrate the dynamics of the brain activity, the scientists performed independent measurements using two different methods. Thirty-six healthy participants were scanned using magnetoencephalography (MEG) and intracranial electroencephalography (EEG) was measured in an epileptic patient. During an MEG scan, subjects sit under a kind of helmet that measures magnetic fields caused by the electrical currents of active nerve cells. “This enabled us to record data that is an expression of the momentary total activity of the brain, without any delay” explains Tobias Staudigl, first author of the study. He is currently conducting research at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles (USA). The participants viewed 200 pictures containing both indoor and outdoor scenes. “In addition to the MEG measurements, we also recorded their eye movements using an eye-tracker to determine how they visually explored the scenes of the images shown.”

In the case of the epileptic patient, the researchers took advantage of the fact that for diagnostic purposes, prior to a brain surgery, he had been implanted with electrodes that could directly record electrical activity in the brain. He was asked to look at similar pictures with indoor and outdoor scenes, as well as with animals and faces. His eye movements were also measured, allowing the scientists to obtain an additional dataset to record the activation patterns of the cells.

“We looked at whether the activity patterns of the entire grid cell system have a specific structure, as has been assumed for a few years,” reports Prof. Doeller. “By showing the subjects pictures of visual scenes, we were able to demonstrate that. This is the first time that this effect has been measured by MEG and EEG recordings, and it opens up many exciting opportunities for further research. For example, it could lead to new biomarkers for diseases such as Alzheimer’s in the future. This is because in young adults with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, we have already seen that the activity of the grid cell system is reduced.”

Source: Christian Doeller – Max Planck Institute

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Anna Hobbiss.

Original Research: Open access research for “Hexadirectional Modulation of High-Frequency Electrophysiological Activity in the Human Anterior Medial Temporal Lobe Maps Visual Space” by Tobias Staudigl, Marcin Leszczynski, Joshua Jacobs, Charles E. Schroeder, Ole Jensen, and Christian F. Doeller in Current Biology. Published October 11 2018.

doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.09.035

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Max Planck Institute”How the Brain’s Grid System Maps Mental Spaces.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 14 October 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/grid-system-spaces-10017/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Max Planck Institute(2018, October 14). How the Brain’s Grid System Maps Mental Spaces. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved October 14, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/grid-system-spaces-10017/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Max Planck Institute”How the Brain’s Grid System Maps Mental Spaces.” https://neurosciencenews.com/grid-system-spaces-10017/ (accessed October 14, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Hexadirectional Modulation of High-Frequency Electrophysiological Activity in the Human Anterior Medial Temporal Lobe Maps Visual Space

Grid cells are one of the core building blocks of spatial navigation [1]. Single-cell recordings of grid cells in the rodent entorhinal cortex revealed hexagonal coding of the local environment during spatial navigation. Grid-like activity has also been identified in human single-cell recordings during virtual navigation. Human fMRI studies further provide evidence that grid-like signals are also accessible on a macroscopic level. Studies in both non-human primates and humans suggest that grid-like coding in the entorhinal cortex generalizes beyond spatial navigation during locomotion, providing evidence for grid-like mapping of visual space during visual exploration—akin to the grid cell positional code in rodents during spatial navigation. However, electrophysiological correlates of the grid code in humans remain unknown. Here, we provide evidence for grid-like, hexadirectional coding of visual space by human high-frequency activity, based on two independent datasets: non-invasive magnetoencephalography (MEG) in healthy subjects and entorhinal intracranial electroencephalography (EEG) recordings in an epileptic patient. Both datasets consistently show a hexadirectional modulation of broadband high-frequency activity (60–120 Hz). Our findings provide first evidence for a grid-like MEG signal, indicating that the human entorhinal cortex codes visual space in a grid-like manner, and support the view that grid coding generalizes beyond environmental mapping during locomotion. Due to their millisecond accuracy, MEG recordings allow linking of grid-like activity to epochs during relevant behavior, thereby opening up the possibility for new MEG-based investigations of grid coding at high temporal resolution.