Summary: Researchers take a new look at the murder of Kitty Genovese, a case that sparked psychologists interest in the bystander effect. Several new studies reveal that there are a number of instances where the facts of the case do not align with the original story, and also uncover evidence of false confessions.

Source: APS.

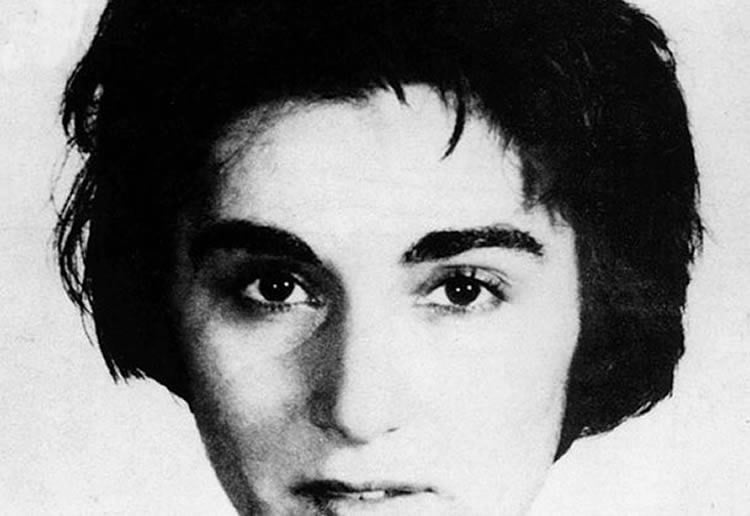

On March 13, 1964 a woman named Catherine “Kitty” Genovese was murdered outside of her apartment in Queens, New York. Over the course of a brutal attack lasting over 30 minutes, Genovese was stabbed at least 14 times. It was widely reported that despite Genovese’s screams for help, not a single one of the 38 bystanders at the apartment that night came to her aid. The case caught the attention of the public, as well as psychological scientists, leading to research on the “bystander effect.”

But new research raises the question: What if we’ve had the story all wrong for the last 50 years?

After painstakingly reviewing historical records on the case, APS Fellow Saul Kassin (John Jay College of Criminal Justice) discovered that many important facts related to the case have been overlooked for decades.

“Although the media spotlight focused on Genovese and her neighbors, other stories closely linked to the event, which are also profound for what they say about human social behavior, were unfolding, only to get lost in the historical record,” Kassin writes.

In a new article in Perspectives on Psychological Science, Kassin points to several instances where the facts of the case don’t quite align with the infamous story; contrary to the version of events in the textbooks, several individuals actually did respond to Kitty’s screams that night, coming to her aid and calling the police. In his examination of the details of the Genovese murder, Kassin also came across several instances of false confessions.

“Psychologists of my generation have been staring at this case for more than 50 years,” he writes. “Yet, like the gorilla pounding its chest in studies of inattentional blindness, the bystander narrative rendered these false confessions all but invisible to history.”

Five days after Genovese’s murder, the police arrested a 29-year-old African American man named Winston Moseley for burglary. According to the police, Moseley gave a full and detailed confession of raping and killing Genovese and several additional women. Moseley confessed to a total of three murders, including 24-year-old Annie Mae Johnson and 15-year-old Barbara Kralik. Despite Moseley’s knowledge of details of these murders, police took no formal statement, and he was never tried for killing Johnson or Kralik.

Why would police refuse to follow up on a detailed confession to two murders? As it turned out, detectives had already obtained confessions from another man for the murder of Kralik.

Months earlier, a White teenager named Alvin Mitchell had confessed to murdering Kralik. The 18-year-old Mitchell had been interrogated by police seven times over 50 hours, after which he signed a confession written by detectives. While in police custody, Mitchell claimed he was threatened and physically abused. He quickly recanted the confession.

Mitchell, not Moseley, was tried for the murder of Barbara Kralik. Moseley even served as a defense witness. Not only did he confess to killing Kralik, but he provided a step-by-step account of the murder, including the detail that a small, serrated steak knife was used as the murder weapon – a detail that had not been made public.

Mitchell’s trial ended in a hung jury and he was eventually convicted during a second trial. Again, Moseley served as a witness, but this time he refused to talk: “I didn’t do it,” he testified, “and I don’t intend to go into any explanation why.”

Mitchell was convicted of first-degree manslaughter. He served 12 years and 8 months before being released. With help from an investigator who volunteered his time, Kassin was able to track Mitchell down.

“I asked Mitchell why he confessed,” Kassin explains. “His reply was simple and to the point: ‘I would have confessed to killing the president because them people had me scared to death.’”

The Genovese case also led Kassin to another set of false confessions. Detectives attempted to get Moseley to confess to two additional killings: 21-year-old Emily Hoffert and 23-year-old Janice Wylie—the so-called “career girl” murders. Moseley flatly denied having anything to do with these crimes.

After 26 hours of high-pressure interrogation, police obtained a confession from George Whitmore, a 19-year-old African American man. Whitmore eventually signed a 61-page confession attributed to him, but immediately recanted it once he was out of police custody. Whitmore said that police had beaten him and that “he had not even read the statement he was pressured to sign.”

Whitemore spent 3 years in jail before he was fully exonerated of all “confessed” crimes. His case was cited in the Supreme Court’s landmark opinion in Miranda v. Arizona as “the most conspicuous” example of police coercion in the interrogation room.

As Kassin’s own research has shown, innocent people can be induced to confess to crimes they did not commit, judges and juries have difficulty assessing the validity of confessions, and reforms are needed to mitigate both sets of problems. One of the most significant safeguards according to Kassin, is requiring the electronic recording of interrogations.

“Twenty-five years ahead of the infamous Central Park Jogger case, the Kitty Genovese case presents a story, or two or three, about a false confession,” Kassin writes. “Despite more than 30 years of scholarly interest in false confessions and a social psychology textbook in its 10th edition, even this social psychologist was not aware of it.”

Source: Melissa Cochrane – APS

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is adapted from the APS news release.

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]APS “A New Look at the Killing of Kitty Genovese: The Science of False Confessions.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 12 July 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/false-confessions-kitty-genovese-7064/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]APS (2017, July 12). A New Look at the Killing of Kitty Genovese: The Science of False Confessions. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved July 12, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/false-confessions-kitty-genovese-7064/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]APS “A New Look at the Killing of Kitty Genovese: The Science of False Confessions.” https://neurosciencenews.com/false-confessions-kitty-genovese-7064/ (accessed July 12, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]