Summary: Following a one year program of aerobic exercise improves memory function and boosts blood flow to brain areas critical for cognition in older adults with risk factors for dementia.

Source: UT Southwestern Medical Center

Scientists have collected plenty of evidence linking exercise to brain health, with some research suggesting fitness may even improve memory. But what happens during exercise to trigger these benefits? New UT Southwestern research that mapped brain changes after one year of aerobic workouts has uncovered a potentially critical process: Exercise boosts blood flow into two key regions of the brain associated with memory. Notably, the study showed this blood flow can help even older people with memory issues improve cognition, a finding that scientists say could guide future Alzheimer’s disease research.

“Perhaps we can one day develop a drug or procedure that safely targets blood flow into these brain regions,” says Binu Thomas, Ph.D., a UT Southwestern senior research scientist in neuroimaging. “But we’re just getting started with exploring the right combination of strategies to help prevent or delay symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. There’s much more to understand about the brain and aging.”

Blood flow and memory

The study, published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, documented changes in long-term memory and cerebral blood flow in 30 participants, each of them 60 or older with memory problems. Half of them underwent 12 months of aerobic exercise training; the rest did only stretching.

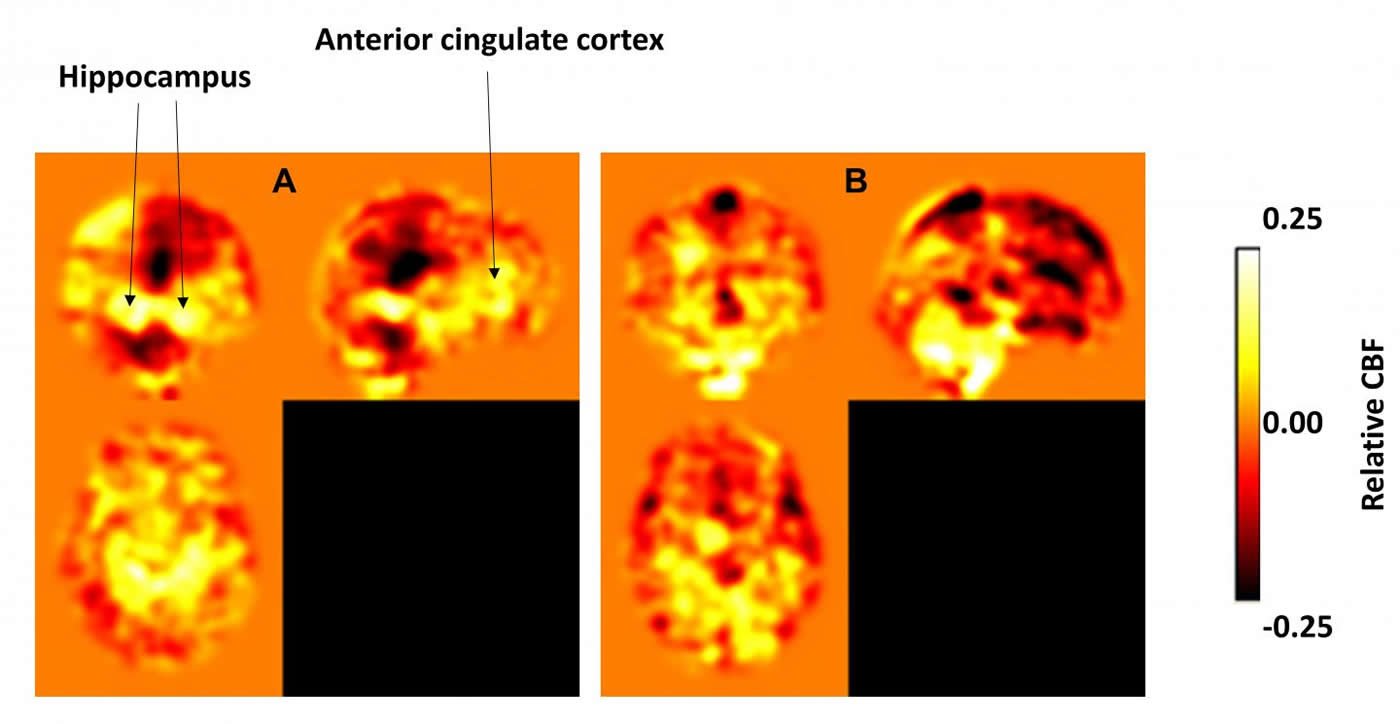

The exercise group showed 47 percent improvement in memory scores after one year compared with minimal change in the stretch participants. Brain imaging of the exercise group, taken while they were at rest at the beginning and end of the study, showed increased blood flow into the anterior cingulate cortex and the hippocampus – neural regions that play important roles in memory function.

Other studies have documented benefits for cognitively normal adults on an exercise program, including previous research from Thomas that showed aging athletes have better blood flow into the cortex than sedentary older adults. But the new research is significant because it plots improvement over a longer period in adults at high risk to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

“We’ve shown that even when your memory starts to fade, you can still do something about it by adding aerobic exercise to your lifestyle,” Thomas says.

Mounting evidence

The search for dementia interventions is becoming increasingly pressing: More than 5 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease, and the number is expected to triple by 2050.

Recent research has helped scientists gain a greater understanding of the molecular genesis of the disease, including a 2018 discovery from UT Southwestern’s Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute that is guiding efforts to detect the condition before symptoms arise. Yet the billions of dollars spent on researching how to prevent or slow dementia have yielded no proven treatments that would make an early diagnosis actionable for patients.

UT Southwestern scientists are among many teams across the world trying to determine if exercise may be the first such intervention. Evidence is mounting that it could at least play a small role in delaying or reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

For example, a 2018 study showed that people with lower fitness levels experienced faster deterioration of vital nerve fibers in the brain called white matter. A study published last year showed exercise correlated with slower deterioration of the hippocampus.

Regarding the importance of blood flow, Thomas says it may someday be used in combination with other strategies to preserve brain function in people with mild cognitive impairment.

“Cerebral blood flow is a part of the puzzle, and we need to continue piecing it together,” Thomas says. “But we’ve seen enough data to know that starting a fitness program can have lifelong benefits for our brains as well as our hearts.”

Funding: The Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease study was supported with funds from the National Institute on Aging. It included collaborations with staff at the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine (IEEM), a partnership between UT Southwestern and Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas.

About this neuroscience research article

Source:

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Media Contacts:

James Beltran – UT Southwestern Medical Center

Image Source:

The image is credited to UTSW.

Original Research: Closed access

“Brain Perfusion Change in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment After 12 Months of Aerobic Exercise Training”. by Thomas, Binu P. et al.

Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease doi:10.3233/JAD-190977

Abstract

Brain Perfusion Change in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment After 12 Months of Aerobic Exercise Training

Aerobic exercise (AE) has recently received increasing attention in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). There is some evidence that it can improve neurocognitive function in elderly individuals. However, the mechanism of these improvements is not completely understood. In this prospective clinical trial, thirty amnestic mild cognitive impairment participants were enrolled into two groups and underwent 12 months of intervention. One group (n = 15) performed AE training (8M/7F, age = 66.4 years), whereas the other (n = 15) performed stretch training (8M/7F, age = 66.1 years) as a control intervention. Both groups performed 25–30 minutes training, 3 times per week. Frequency and duration were gradually increased over time. Twelve-month AE training improved cardiorespiratory fitness (p = 0.04) and memory function (p = 0.004). Cerebral blood flow (CBF) was measured at pre- and post-training using pseudo-continuous-arterial-spin-labeling MRI. Relative to the stretch group, the AE group displayed a training-related increase in CBF in the anterior cingulate cortex (p = 0.016). Furthermore, across individuals, the extent of memory improvement was associated with CBF increases in anterior cingulate cortex and adjacent prefrontal cortex (voxel-wise p < 0.05). In contrast, AE resulted in a decrease in CBF of the posterior cingulate cortex, when compared to the stretch group (p = 0.01). These results suggest that salutary effects of AE in AD may be mediated by redistribution of blood flow and neural activity in AD-sensitive regions of brain.

Feel Free To Share This Neuroscience News.