Berlin researchers test mechanisms involved in decision-making.

The background to this new set of experiments lies in the debate regarding conscious will and determinism in human decision-making, which has attracted researchers, psychologists, philosophers and the general public, and which has been ongoing since at least the 1980s. Back then, the American researcher Benjamin Libet studied the nature of cerebral processes of study participants during conscious decision-making. He demonstrated that conscious decisions were initiated by unconscious brain processes, and that a wave of brain activity referred to as a ‘readiness potential’ could be recorded even before the subject had made a conscious decision.

How can the unconscious brain processes possibly know in advance what decision a person is going to make at a time when they are not yet sure themselves? Until now, the existence of such preparatory brain processes has been regarded as evidence of ‘determinism’, according to which free will is nothing but an illusion, meaning our decisions are initiated by unconscious brain processes, and not by our ‘conscious self’. In conjunction with Dr. Benjamin Blankertz and Matthias Schultze-Kraft from Technische Universität Berlin, a team of researchers from Charité’s Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience, led by Dr. John-Dylan Haynes, has now taken a fresh look at this issue. Using state-of-the-art measurement techniques, the researchers tested whether people are able to stop planned movements once the readiness potential for a movement has been triggered.

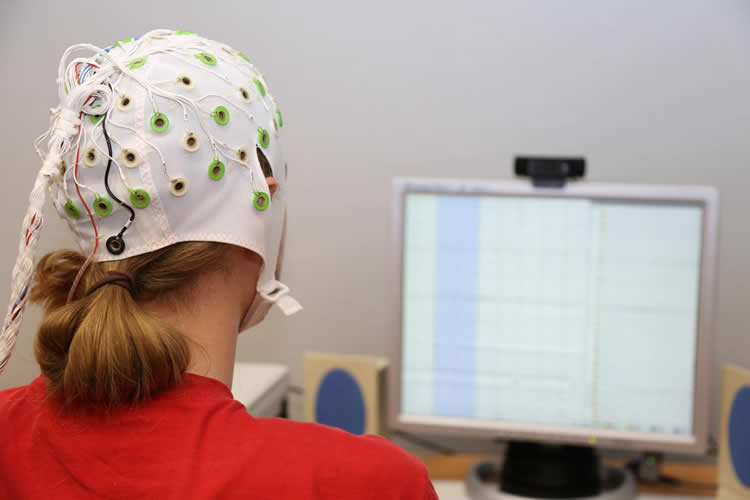

“The aim of our research was to find out whether the presence of early brain waves means that further decision-making is automatic and not under conscious control, or whether the person can still cancel the decision, i.e. use a ‘veto’,” explains Prof. Haynes. As part of this study, researchers asked study participants to enter into a ‘duel’ with a computer, and then monitored their brain waves throughout the duration of the game using electroencephalography (EEG). A specially-trained computer was then tasked with using these EEG data to predict when a subject would move, the aim being to out-maneuver the player. This was achieved by manipulating the game in favor of the computer as soon as brain wave measurements indicated that the player was about to move.

If subjects are able to evade being predicted based on their own brain processes this would be evidence that control over their actions can be retained for much longer than previously thought, which is exactly what the researchers were able to demonstrate. “A person’s decisions are not at the mercy of unconscious and early brain waves. They are able to actively intervene in the decision-making process and interrupt a movement,” says Prof. Haynes. “Previously people have used the preparatory brain signals to argue against free will. Our study now shows that the freedom is much less limited than previously thought. However, there is a ‘point of no return’ in the decision-making process, after which cancellation of movement is no longer possible.” Further studies are planned in which the researchers will investigate more complex decision-making processes.

Source: Dr. John-Dylan Haynes – Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Image Credit: The image is credited to Charité, Carsten Bogler

Original Research: Full open access research for “The point of no return in vetoing self-initiated movements” by Matthias Schultze-Kraft, Daniel Birman, Marco Rusconi, Carsten Allefeld, Kai Görgen, Sven Dähne, Benjamin Blankertz, and John-Dylan Haynes in PNAS. Published online December 14 2015 doi:10.1073/pnas.1513569112

Abstract

The point of no return in vetoing self-initiated movements

In humans, spontaneous movements are often preceded by early brain signals. One such signal is the readiness potential (RP) that gradually arises within the last second preceding a movement. An important question is whether people are able to cancel movements after the elicitation of such RPs, and if so until which point in time. Here, subjects played a game where they tried to press a button to earn points in a challenge with a brain–computer interface (BCI) that had been trained to detect their RPs in real time and to emit stop signals. Our data suggest that subjects can still veto a movement even after the onset of the RP. Cancellation of movements was possible if stop signals occurred earlier than 200 ms before movement onset, thus constituting a point of no return.

“The point of no return in vetoing self-initiated movements” by Matthias Schultze-Kraft, Daniel Birman, Marco Rusconi, Carsten Allefeld, Kai Görgen, Sven Dähne, Benjamin Blankertz, and John-Dylan Haynes in PNAS. Published online December 14 2015 doi:10.1073/pnas.1513569112